Begin forwarded message:

From: Mark Terry

Subject: Re: Imagineering reading for Wednesday’s Future Cinema class

Date: September 25, 2016 at 11:21:54 AM EDT

To: Caitlin Fisher

Hi Caitlin!

Since we’ve been having difficulty tracking down copies of Soctt Lucas’ The Immersive Worlds Handbook (and as part of our class assignment to find related texts on the subject), I’d like to offer to you, the class and the course, a PDF of his latest book, A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces (2016).

One of my PhD committee members, Markus Reisenleitner from our Humanities department, uploaded this text – the complete book – to Academia.edu. Both he and Susan Ingram (also from our Humanities department) have contributed chapters in this book. If you want to add this to future reading lists for the course, you can ensure all students will be able to have a copy. And best of all, it’s current and contains academic work from a variety scholars on the subject.

Here is the link to the PDF: https://www.dropbox.com/s/91svkwjqwk3e0bo/A_Reader_In_Themed_and_Immersive_Spaces.pdf?dl=0

It’s too big to share as an attachment (18 MB), but if you want to upload it to the Future Cinema website, it can be downloaded from there.

Mark

At this late date I don’t expect you will be able to read the entire book, but selecting one chapter in addition to the chapter i uploaded for all of us to read would give us a good foundation for conversation!

*n.b. I have also uploaded the file to the class site: http://www.yorku.ca/caitlin/readings/A_Reader_In_Themed_and_Immersive_Spaces.pdf*

Mon, September 26 2016 » Future Cinema » No Comments » Author: Caitlin

Hi everyone, apologies for the late arrival of the reading… and Thanks, David, for finding the first part of this chapter! As stated in class, given difficulties with finding the text (back-ordered n Amazon) I am making the first chapter of the Imagineering book available here as a PDF. It would be too time-consuming to provide you with the full book… so i challenge you to read this and maybe think of other texts/theorists/examples you can bring to the conversation.

http://www.yorku.ca/caitlin/imagineering_chapter1.pdf

Sat, September 24 2016 » Future Cinema » No Comments » Author: Caitlin

I set the site to ‘allow anyone to register’ thinking registrants would be members of this class! Unfortunately hundreds of spammers were more enthusiastic. I think I’ve fixed thigs – but i’ll need to register you all as users manually now – we can do it Wednesday.

Fri, September 16 2016 » Future Cinema » No Comments » Author: Caitlin

Great meeting you all today.

The syllabus is available for download here:

http://www.yorku.ca/caitlin/futurecinemas/?page_id=6

Readings for week two are available online via this website – check out the online reading section.

Your first assignment is also due week two.

Try to get to FIVARS on the weekend!

see you next week!

Wed, September 14 2016 » future cinema 2015 » No Comments » Author: Caitlin

Here is my final project: an online pitch and a trailer for an interactive documentary titled CENSOR.SWEATSHOP (click title and it will open in a new window)

Tue, December 8 2015 » future cinema 2015 » No Comments » Author: Nanna Rebekka

This Ada Lovelace doc is screening at The Revue next weekend: https://www.facebook.com/events/200915890245789/

Thu, November 26 2015 » future cinema 2015 » 1 Comment » Author: Andi Schwartz

“Tactical Media” is a chapter in the book Protocol: How Control Exists After Decentralization (2004) by Alexander Galloway. Galloway’s central argument is that the internet is a space of control.

Earlier in the text, Galloway defines protocol as “a set of rules that defines a technical standard. But from a formal perspective, protocol is a type of object. It is a very special kind of object. Protocol is a universal description language for objects. Protocol is a language that regulates flow, directs netspace, codes relationships, and connects life-forms” (p. 74).

Galloway argues that protocol can be interpreted or analyzed just as any other language, because code is the language of computers.

The chapter we are focusing on for this class is called “Tactical Media.” In this chapter, Galloway examines instances of online subversion and resistance, which pose challenges to protocol. He characterizes these conflicts as network-based conflicts, or conflicts between different diagrams.

Galloway says tactical media is “the term given to political uses of both new and old technologies, such as the organization of virtual sit-ins, campaigns for more democractic access to the Internet, or even the creation of new software products not aimed at the commercial market” (p. 175).

Computer Viruses

He begins the chapter by examining computer viruses, and uses them as an example to illustrate network-based conflict.

Drawing from computer virus scholar Frederick Cohen, Galloway says “viruses” are computer programs that modify other programs by inserting a version of itself into the new program. All viruses, whether worms, Trojan horses, etc. are characterized as negative.

Galloway argues that the cultural moment that computer viruses arrived in are responsible for this negative characterization. This cultural moment included the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, which explains the biological associations. Galloway charts the shift from biological metaphors (AIDS, infection, virus) to criminal metaphors (terrorism, weaponization, criminals), and argues that these different threat paradigms, AIDS and terrorism, represent different diagrams.

Galloway notes that many virus authors say the virus is not the problem, but the flaws in the affected program are; viruses simply exploit these flaws. Viruses point out other flaws that are not technologically based, like corporate monopolies.

Viruses originated as games for engineers, people who Galloway says prized creativity, technical innovation, and exploration.

Cyberfeminism

Galloway’s chapter moves into a discussion of cyberfeminism, a 1990s movement that addressed the relationship between women and machines, and the masculinization of technology. Cyberfeminism became an international movement, but Galloway initially highlights the Australian group VNS Matrix who wrote the first Cyberfeminist Manifesto in the early 90s. Galloway quotes Faith Wilding and the Critical Art Ensemble: “The territory of cyberfeminism is large. It includes [...] those arenas in which technological process is gendered in a manner that excludes women from access to the empowering points of technoculture” (p. 187).

Galloway positions cyberfeminism as another type of tactical media, one that shares functions with computer viruses, or bugs in the protocological network, which can propel technology in interesting ways. He says, “With cyberfeminism, protocol becomes disturbed. Its course is altered and affected by the forces of randomness and corruption” (p. 185).

Another major cyberfeminist theorist that Galloway highlights is Sadie Plant, who argues that technology is fundamentally female, and makes it her project to recover the history of the relationship between women and machines. In her works she notes women’s close proximity to machines through history, starting with the loom. She has argued that computer programming actually emerged from the tradition of weaving (Plant, “The Future Looms” 1995); that women have made up the core labour of telecommunications (Plant, Zeros and Ones 1997); and has written extensively about Ada Lovelace and her role as a computer programmer (Plant 1995, 1997; Galloway 2004, p. 185).

Plant argues that this history threatens phallic control and thus technology is a process of emasculation and an opportunity to weaken the patriarchy. According to Galloway, this marks a move from centralized control to a distributed network.

Though cyberfeminism encompasses many strands and perspectives, Galloway says that the themes of body and identity are central to the movement. Theorist Allucquère Rosanne Stone / Sandy Stone in particular examined the relationship between materiality and meaning that constitute bodies in cyberspace. She argued that online spaces mirror our “Cartesian” understanding of physical space. In other words, bodies are still gendered (and subject to other social hierarchies) in cyberspace. (This has also been argued by other scholars, like Lori Kendall [1998].) However, Stone says that since communications technologies help produce online identities, communities, and provide a mode to navigate both of these things together, tactical media like cyberfeminism presents an opportunity to refashion the organization and understanding of space.

The role of the body in cyberfeminism and in cyberspace is fraught, as demonstrated by Lynn Hershmann’s claim that the internet prompted the largest immigration in history — from offline to online. Plant argues that it is about reshaping matter, rather than escaping it.

Conflicting Diagrams

Galloway introduces John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt’s term “netwar,” which refers to “an emerging mode of conflict (and crime) at societal levels, short of traditional military warfare, in which the protagonists use network forms of organization and related doctrines, strategies and technologies attuned to the information age” (p. 196).

Galloway says peer-to-peer, bureaucracy, and hierarchy are all diagrams; peer-to-peer (or distributed network) is the diagram of the internet. Gene Youngblood argues this as well.

Like the rhizome is thought to be a solution to the tree, Galloway argues that viruses and cyberfeminism are network conflicts a solution to hierarchies; network conflicts are essentially conflicts between different social structures or diagrams.

Galloway writes that increasingly, decentralized and distributed networks are being adopted: the internet was invented to avoid “certain vulnerabilities of nuclear attack” (p. 200), and cities are being designed with industrial targets outside of the urban core. In other words, the bomb or threat of destruction drives dispersion. Following this logic, Galloway argues that the internet is strong because it is weak, because its power is distributed or decentralized. Similarly, hierarchies are weak because they are strong, because its power is centralized.

Using these examples: terrorism is the only real threat to state power, homeless punk rockers are the only threats to sedentary domesticity, and the guerilla is the only threat to the war machine, Galloway argues that hierarchies cannot fight networks; only networks can fight networks.

He says “This is indicative of two conflicting diagrams. The first diagram is based on the strategic massing of power and control, while the second diagram is based on the distribution of power into small, autonomous enclaves” (p. 201).

Just as he says this should give subcultures reason to rethink their strategies, he suggests we take this kind of thinking and apply it to media.

Questions

Criminal charges can be laid for computer viruses, virtual damages can be assessed, and the advent of cyberspace is said to have sparked the largest immigration in history — from offline to online; how do these notions tangle with Baudrillard’s concerns about disappearing space and the ecstasy of communication, but also with Youngblood’s call to leave the culture without leaving the country?

What are the limits of using binary code to dismantle hierarchies? Can Plant’s argument that as “protocol rises, patriarchy declines” be used for dismantling other social hierarchies, other than gendered ones?

Plant argues that women have traditionally comprised the laboring core of networks of all kinds, particularly the telecommunications networks. When we consider the histories she presents, this is true! Many other forms of women’s labour are similarly necessary, yet unseen or unrecognized. How do in/visibility and marginality make this possible? Is there any benefit of being invisible while being at the centre of something so fundamental?

How does tactical media relate to future cinema?

How can tactical media be seen as a solution to the crisis Gene Youngblood describes?

Tue, November 24 2015 » future cinema 2015 » No Comments » Author: Andi Schwartz

This is the film I mentioned as being of interest to us following Nanna’s show-and-tell of her own film.

“Women are the focus but not the object of Trinh T. Minh-ha’s influential first film, a complex visual study of the women of rural Senegal. Through a complicity of interaction between film and spectator, REASSEMBLAGE reflects on documentary filmmaking and the ethnographic representation of cultures.

“With uncanny eloquence, REASSEMBLAGE distills sounds and images of Senegalese villagers and their surroundings to reconsider the premises and methods of ethnographic filmmaking. By disjunctive editing and a probing narration this ‘documentary’ strikingly counterpoints the authoritative stance typical of the National Geographic approach.” — Laura Thielan

http://www.wmm.com/filmcatalog/pages/c52.shtml

Wed, November 18 2015 » future cinema 2015 » No Comments » Author: Caitlin

3D FILMS THAT GO TO UNEXPECTED PLACES

http://tiff.net/addeddimensions

lots of 3D possibilities at TIFF this week (you can purchase tickets via the link) including:

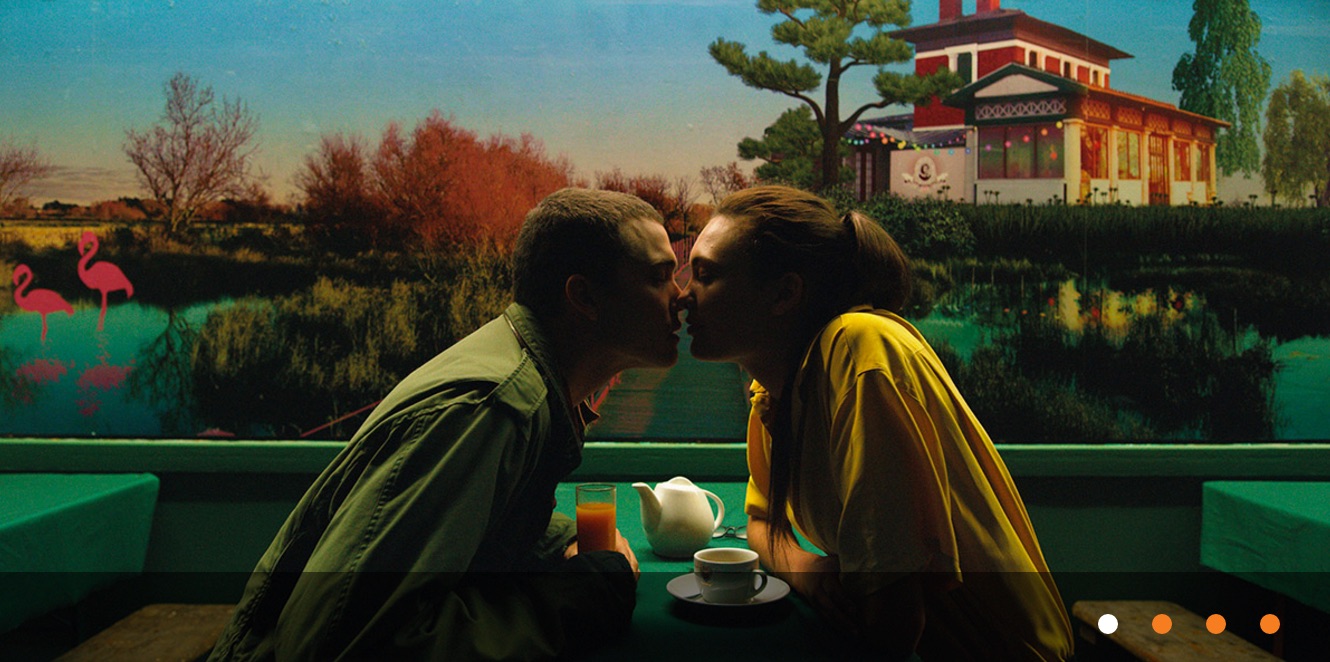

Love

Directed by Gaspar Noé

(R)

French provocateur Gaspar Noé (Enter the Void) continues to push the envelope with this 3D melodrama featuring explicit, unsimulated sex.

Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival 2015

Wed, November 18 2015 » future cinema 2015 » No Comments » Author: Caitlin

In his essay “What is Digital Cinema?” Lev Manovich notes that the majority of discussion around digital cinema has focused on the possibilities of narrative interaction. Manovich argues that this focus on narrative only addresses one aspect of cinema, which is neither unique nor essential to the medium.

For Manovich the challenge presented by digital media extends beyond the issue of narrative to the very identity of cinema. With enough time or money anything can be simulated in a computer, reducing the filming of physical reality to just one of many options available to filmmakers.

He invokes French theorist Christopher Metz in noting that most films possess the common characteristic of telling a story, to which Manovich adds most films are live action films consisting unmodified recordings of real events which took place in real physical space.

The development of a whole repertoire of techniques during the history of cinema (lighting, art direction, various film stocks and lenses) are ultimately rooted in attempts to obtain deposits from reality.

What do you think of Manovich’s statement in which he refers to Cinema as the “art of the index” an attempt to make art out of a footprint? Does the identity of Cinema lay in its ability to record reality? Does it merely start the film rolling and record whatever happens to be in front of the lens?

Manovich argues that the indexical identity of cinema is challenged by photorealistic computer generated images which are perfectly credible despite never having been filmed. The return to the manual construction of images means that cinema can no longer be distinguished from animation.

Is cinema no longer an indexical media technology, but rather a sub-genre of painting?

Manovich points to the original names by which cinema was referred (kinetoscope, cinematograph, and moving pictures) as indicative of how it was understood, as the art of motion, one which superseded previous techniques for creating and displaying moving images.

These earlier techniques shared several characteristics. They relied on hand-painted or hand-drawn images and they were manually animated.

Robertson’s Phantasmagoria

The predecessors of cinema also possessed discrete characteristics of space and movement. The moving element was visually separated from the static background, and was limited in range and affecting only a clearly defined figure rather than the whole image.

Film before Film

All of these animations were based around loops, sequences of images which can be played repeatedly. Advances in technology allowed for the automatic generation of images as well as the automatic projection, allowing for the adoption of longer narrative form.

With the stabilization of cinema technology, Manovich argues that all references were cut to its origins in artifice. The manual construction of images, loop actions, and the discrete nature of space and movement were relegated to animation.

How do elements such as costume, lighting and set design fit into Manovich’s notion of “artifice?” Is employment of these cinematic techniques by animators a result of the same technological limitations that had formerly constrained live action film?

Manovich suggests that the opposition between animation and cinema defined the culture of the moving image in the 20th century. Animation is more aligned to the graphic, foregrounding its characters and admitting that its images are merely representation. Cinema attempts to erase any traces of its own production process and is more aligned with the photographic.

Having examined the development of cinema and its precursors Manovich sets out to define digital cinema, which argues follows several principles. Computers can generate film-like physical reality, displacing live action footage as the only possible material from which a film is constructed. Live action footage now functions as raw material for further manipulation, creating a new kind of “elastic reality.” Computer technology has collapsed the distinction between editing and special effects, making them part of the same operation.

Manovich’s answer to question of defining digital cinema is that it is a “particular case of animation which uses live action footage as one of its many elements. Cinema was born from manual construction and animation of images, animation was pushed to the margins only to reappear as the foundation of digital cinema. Shot footage is but raw material to be manipulated in a computer. Production has become just the first stage of post-production.

The mutability of the digital image means that the cinematic image is no longer locked in the photographic. Hand painted digitized film frames represent a return of cinema to its origins in the hand-crafted images of its precursors.

Commercial narrative cinema continues hold on to its realist style in which images function as photographic records of events. Manovich references Metz analysis made in the 1970’s in contemplating the possibility of a greater number of non-narrative films in the future. Manovich gives the examples of the music video and the CD-ROM video game. He argues that video games have followed a similar development path to cinema when faced with some of the same technological limitations, relying on still images and animations, and looped clips. This teleological development replays the emergence of cinema a hundred years earlier, progressing from still images to moving characters over static backgrounds to full motion.

History, Manovich suggests, is not linear march toward one possible language, but a succession of distinct and equally expressive languages, each with its own aesthetic variables. The visual strategies of early multimedia titles may be a result of technological limitations, but it can also be seen as the beginning of digital cinema’s new language.

Jean-Louis Boissier’s Flora petrinsularis

Flora petrinsularis is an interactive CD-ROM program in which the viewers attempts to generate a narrative creates a loop, a structure which becomes a metaphor for human desire which can never achieve resolution. It can also be read as a comment on cinematic resolution.

Manovich’s own “Little Movies” is explicitly modeled after the peep-hole machines of Kinetoscope parlors, drawing a parallel between them and the tiny QuickTime videos of the digital era. Through this work Manovich begins to explore the concept of “spatial montage” between simultaneously co-exiting images. By making images different size and having them appear and disappear in different parts of the screen without any obvious order, Manovich seeks to present the screen as a space of endless possibilities.

Little Movies

In conclusion Manovich argues that the mutability of digital date impairs the value of cinema recordings as documents of reality. Cinematic realism is being displaced from being the dominant mode of moving image culture to become one of only many options.

Tue, November 17 2015 » future cinema 2015 » No Comments » Author: Jeff Young