GL/SOCI 4645 6.0 (EN): Mobs, Manias and Delusions:

Sociological and Psychoanalytic Perspectives

(last update: April 27th, 2015)

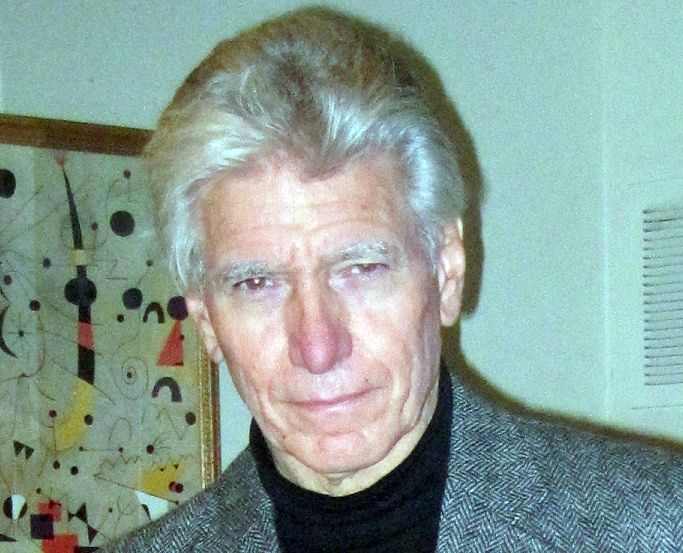

Instructor: Prof. D. Carveth

Web: www.yorku.ca/dcarveth

Email: dcarveth@yorku.ca

Tests are now available for viewing but not removing in the Sociology office.

Final essays now (Monday, April 27th) available for pickup.

Grades have been submitted.

Course Description

A

survey of some classic and modern sociological and psychoanalytic contributions

to the study of mass psychology, with special reference to the understanding of

mobs, manias of various types, hysterical epidemics, and mass illusions and

delusions. Topics include: the rational and irrational in social life; problems

of definition and value judgment; classic studies of

group psychology and religion; the open and the closed mind; hysteria, past and

present. The course will begin with an introduction to Freudian and Kleinian psychoanalytic theory, the perspectives we will

utilize to study mobs, manias and delusions. In this course we seek to study

the irrational in social life and to do this we need to understand the role of

unconscious mental processes—ideas, phantasies and

emotions—in the life of individuals and groups.

On Rationality and Irrationality

For the purposes of this course,

rationality is defined instrumentally as human experience, belief, thought and

conduct congruent with reason, logic and evidence—that is, with the world-view

of empirical science. Since science is restricted to the field of facts rather

than values, being descriptive rather than prescriptive, and unable to deduce

an “ought” from an “is,” it is not competent to posit or evaluate value

judgments. This is the so-called fact/value disjunction. It follows that value

judgments cannot be claimed to be either rational or irrational, since

rationality applies only to means-end relations, not to the positing of ends in

themselves. This fact is frequently obscured by the use of the term

“reasonable”: we say someone is a reasonable person, which sounds as if we are

saying they employ reason and strive to be rational in their thought and

behavior, when what we often actually mean is that from our standpoint they are

“good” or agreeable to us. If we say a person’s politics are reasonable, do we

mean he or she tries to rationally work out the implications of his or her

value commitments (say to privatization or collectivization), or do we mean

that such value commitments are good or agreeable to us? Very often when we

describe something as reasonable we are disguising a subjective value judgment

as an objective statement of fact.

It is irrational to build a bridge

capable of carrying a heavy load out of cardboard rather than stone or steel.

But whether or not it is rational to build a bridge at all cannot be rationally

determined—unless the question is turned into a means-end determination: in

order to transport heavy materials across the river it may well be rational to

build a bridge. In this perspective, irrationality entails holding beliefs that

are contrary to logical reasoning and empirically verified evidence, and

behaving in ways that contradict valid means-end relations. If we want rain,

resorting to a rain dance is irrational, while seeding clouds is not. If a

person diagnosed with cancer foregoes all medication and allied treatment in

favor of fervent prayer, we would consider this behavior irrational. That

prayer appears rational to the subject doesn’t make it rational: he or she is

engaged in magical thinking, resorting to means that have no evidentiary

connection with the desired ends. (If empirical evidence accrues that prayer

helps cure cancer, then praying would be rational. But in the absence of such

evidence some churches hedge their bets: if someone suffering from cancer stops

treatment in favor of fervent prayer, church elders often order its resumption

on the grounds that it is through such treatment that “God” works to answer

prayer.)

But matters become much more complicated

if we introduce the distinction between one’s conscious and unconscious

motivations or goals. If, for example, we were to discover that the cancer

sufferer was unconsciously suicidal, then we would have to revise our view of

his or her behavior, for praying instead of receiving treatment is a rational

means toward this end (death). If a person’s conscious goal is promotion and

advancement in the company he works for, his act of hitting on his boss’s

trophy wife at the Christmas party must be considered an irrational act—unless

his unconscious goal is to get fired, or his incompatible competing goal of

seducing the boss’s wife is far more important to him than his job. If a person

has enrolled in medical school and purchased medical texts but never attends classes

or reads these texts and spends all his time reading philosophy instead without

being enrolled in a philosophy program, we can say his behavior is

irrational—unless we were to discover that his unconscious goal is to fail out

of medical school, in which case his behavior possesses a degree of

rationality. So what looks on the surface to be irrational, may in light of

unconscious factors appear rational after all. What is irrational from the

standpoint of consciously stated goals may be rational from the standpoint of

unconscious goals. In this light, psychoanalysis is less a matter of exposing

the irrationality of human behavior than it is about revealing the hidden or

latent rationality beneath manifestly irrational experience and behavior.

But does this then mean that in light of psychoanalytic understanding of unconscious motivation we must abandon any attempt to distinguish rational and irrational behavior—that, in fact, all behavior is revealed as rational if unconscious factors are taken into account? This would be an unnecessary, false and, in my view, irrational conclusion. Sometimes behavior that seems irrational is shown to be rational in light of its unconscious goals. But at other times behavior that seems irrational remains irrational even when the unconscious goals for engaging in it are understood. Understanding, for instance, that believing in astrology lowers a person’s anxiety by providing the feeling that events have meaning and can be predicted, understood and perhaps even to a degree controlled through astrological knowledge doesn’t make such belief any the less irrational. Science too can lower anxiety by providing knowledge, only in this case the knowledge concerned is real rather than pseudo-scientific and spurious. Revealing a person’s unconscious reasons for being irrational doesn’t eliminate the irrationality. A person who engages in extensive projection of his own repressed feelings into others will suffer defective reality-testing as a result. Understanding the unconscious reasons and mechanisms involved does not alter the irrationality of the outcome. So it appears there are different types of irrationality, some that turn out not to be irrational at all in light of unconscious goals, and others that remain irrational even in light of the unconscious factors that motivate it. Psychoanalytic understanding of unconscious factors in no way forces us to embrace a postmodern relativism that considers judgments of rational and irrational merely subjective expressions of personal taste or social conformity lacking in objectivity. Such a conclusion is itself revealed to be irrational.

Although hardly adhering to reason and science in a good deal of his own work, at least in this statement denouncing relativism Terrence McKenna clearly articulates the standpoint from which the present course is taught: Terence Mckenna denounces Relativism - YouTube

See also: Why Are Reasonable People At War With Scientific Consensus? | Portside

A “mass hysteria” (as distinct from an “hysterical epidemic”): The Mystery of 18 Twitching Teenagers in Le Roy - NYTimes.com

Denial: Half of Americans Think Climate Change Is a Sign of the Apocalypse - The Atlantic

Carveth review of Kolbert (2014), The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History

Woody Allen on Hypochondria: Hypochondria - An Inside Look - NYTimes.com

Complete works of Freud available as a free download here

Jonathan Shedler, Psychoanalysis for Psychologists

Jonathan Shedler, The Efficacy of Psychoanalytic Therapy

Mark Solms Interview: Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience

Freud's theory of unconscious conflict linked to anxiety symptoms

A Case for Psychoanalysis: Exploring the Scientific Evidence - YouTube

Are we born with a moral core? The Baby Lab says 'yes' - CNN.com

Required

Bion, W.R. (1959). Experiences in Groups.

Caper, R. (2000). Immaterial

Facts: Freud's Discovery of Psychic Reality and Klein's Development of His

Work.

Carveth, D.L. & Jean Hantman Carveth (2003). "Fugitives

From Guilt: Postmodern De-Moralization and the New

Hysterias." American Imago 60, 4 (Winter 2003):

445-80.

Freud, S. (1915-16). Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. S.E., 15.

-----. (1921).

Group

Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego S.E.,

18.

-----. (1927).

The Future of an Illusion. S.E., 21: 3-58.

-----. (1930).

Civilization and Its

Discontents, S.E., 21: 57-146.

-----. (1933).

“The Dissection

of the Psychical Personality.” Lecture 31, New

Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, S.E., 22.

-----. (1933). “Revision of the

Dream Theory.” Lecture 29, New Introductory Lectures on

Psychoanalysis, S.E., 22.

Klein, M. (1959). “Our

Adult World and its Roots in Infancy.” Envy and Gratitude and

Other Works, 1943-1963.

Shedler, J. (2006). That Was Then, This Is Now: An Introductioin to Contemporary Psychodynamic Therapy. Unpublished online MS.

Showalter, E. (1997). Hystories:

Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Media.

Stevenson, L. & D. Haberman

(2004). “Freud: The Unconscious Basis of

Mind.” Ten Theories of Human Nature, 4rth

ed.

Recommended

Alford, C. Fred. (1989). Melanie

Klein and Critical Social Theory: An Account of Politics, Art, and Reason based

on Her Psychoanalytic Theory.

chapters 1-2.

Carveth, D. (2013). The Still Small Voice: Psychoanalytic Reflections on Guilt and Conscience. London: Karnac Books.

Gentile, E. (2006).

A Never-Never Religion, a Substitute for Religion, or a New

Religion?

Chapter 1 in: Gentile, E., Politics

as Religion.

Princeton

University Press, 2006.

Golding, Wm. (1958).

Lord of the Flies

Küng, H. (1990). Freud

and the Problem of God. Enlarged ed.

Meerloo, J. (1949). Delusion and Mass-Delusion.

-----. (1962). Suicide and Mass Suicide.

Meissner, W. (1984). Psychoanalysis

and Religious Experience.

Miller, A. (1971). The Crucible. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1977.

Mitchell, J. (2000). Mad Men and Medusas:

Reclaiming Hysteria.

Mulhern, S. (1994). “Satanism, Ritual Abuse, and Multiple

Personality Disorder.” International Journal of Clinical

and Experimental Hypnosis 42 (October

1994):

266.

Shorter, E. (1992). From Paralysis to

Fatigue: A History of Psychosomatic Illness in the Modern Era.

Recommended:

Ebola Hysteria Fever: A Real Epidemic

The Serial Killer has Second Thoughts: the Confessions of Thomas Quick

Compliance (2012). When a prank caller convinces a fast food restaurant manager to interrogate an innocent young employee, no-one is left unharmed. Based on true events.

The Milgram Experiements on Obedience

The King’s Speech.

Tom Hooper, Dir. Perf.

Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush. Momentum Pictures, 2010.

The Rapture (1995).

New Line Cinema. Produced by Nick Wechsler, Nancy Tenenbaum

and Karen Koch; written and directed by Michael Tolkin.

Rapture: The belief held by many conservative Christians that Christ will soon

appear in the sky and that all of saved individuals, both living and dead, will

rise to meet him.

Lord of the Flies (1963). Directed by Peter Brook. Diamond

Video, 1963. Cast: James Aubrey, Tom Chapin, Hugh Edwards. Credits: Written by

William Golding, based on his novel of the same title. Originally

released as a motion picture in 1963. Abstract: A group of British

schoolboys being evacuated from

The Crucible (1998).

Twentieth Century Fox ; a Nicholas Hytner film ; a

David V. Picker production ; screenplay by Arthur Miller ; produced by Robert

A. Miller and David V. Picker ; directed by Nicholas Hytner.

Safe (1995).

Chemical Films in association with Good Machine, Kardana

Productions, Channel 4 Films ; produced by Christine Vacs

ihon and Lauren Zalaznick ;

written and directed byTodd Haynes. Sony

Pictures Classics: distributed exclusively in

(119 min.). Cast: Julianne Moore, Peter

Friedman, Xander Berkeley, Susan Norman, Kate

McGregor Stewart, James Legros. Credits:

Cinematography, Alex Nepomniaschy ; film editing,

James Lyons; original music, Ed Tomney. Rated

R. Abstract: Carol White, a suburban housewife, finds her affluent environment

suddenly turning against her. Personal author: Haynes, Todd.

Corporate author: Chemical Films (Firm).

Requirements:

Two one-hour tests at the end of each term worth 10%

each, and two major essays each term worth 40% each. The first essay will

review selected classic contributions to the study of the irrational in social

life. The second will involve researching, describing and analyzing a mania, a

mass illusion or delusion, a mass hysteria or hysterical epidemic, utilizing

concepts and theoretical perspectives studied in this course.

First Term Essay: Friday, Dec. 5th, before 4:30 p.m., in C213. Submit typed work only; keep an electronic copy.

1. What do the Freudian and Kleinian psychoanalytic perspectives have to teach us about irrational human experience and behavior?

2. Write an essay on the theme of what psychoanalysis teaches us about the ways we manage not to know ourselves that includes defining, explaining and illustrating at least ten mechanisms of defence.

Second Term Essay

Identify a suitable mania, illusion, delusion, mass hysteria,

hysterical epidemic, irrational group behavior or, in Terrence McKenna's words,

one of the "pernicious forms of idiocy that flourish in our own communties" and research it, describe it, and

analyze it utilizing perspectives and concepts reviewed in this course.

Essay Instructions: (click here for further tips on essay style

and presentation)

1. It is essential that you discuss your

essay topic thoroughly before beginning to write so that you are quite clear

about what is expected.

2. Students may generate essay topics of their own only with the

explicit written permission of the instructor.

3. Remember you are writing, not for the instructor, but for the

intelligent lay person who has not taken this course. Define all key terms.

4. Lectures are designed as a guide to your own research.

Essays which merely regurgitate lecture notes will not be accepted.

Do not quote or refer to lectures

in your essays; work with relevant texts instead.

5. Form, style, syntax, grammar, spelling, punctuation, etc., are as

important as the content of your essay. Have someone proof-read your essay

before handing it in.

6. The "in text" reference system is to be used. For

an illustration of this system see: Carveth, D.

(1993),

"The

Borderline Dilemma in Paris, Texas: Psychoanalytic Approaches to Sam Shepard." Canadian Journal of

Psychoanalysis/Revue canadienne de psychanalyse 1, 2: 19-46.

7. Length: Approximately 2500 words or ten typed and double-spaced pages (Times New

Roman 12).

8. Students who wish to express their

solidarity with feminism linguistically should consistently write

"she", "her", etc.,

or alternate the masculine and feminine forms, rather than "he/she",

"him/her", etc.

9.

Deliver essays to C213 (slot in door). Remember to keep a copy on file.

10. Please use complete justification of

the text (as distinct from left justification).

11. In your first reference to a book

provide in brackets it's year of first publication. As long as you

continue to refer to this book

you need not repeat the bracketed reference; when you turn to a different book

by this author, or a book by another author,

provide the bracketed date.

13. In your test refer to dates of first

publication if possible, but in your bibliography include the year of publication

of the edition you are using.

14. Do not write excessively long

paragraphs. Each paragraph should contain one main idea. When you

shift to another idea start a new paragraph.

15. Do not sacrifice clarity in an attempt to write elegantly.

16.

Keep the use of online resources for essays to an

absolute minimum. Read books and journal articles. Do not quote or

make reference to Wikepedia as it is

not a valid academic resource, though

it may refer you to valid academic sources which may be referenced.

17.

Late penalties apply after due date at the rate of 5% of the grade earned per

day (e.g., one day late would drop you from 80% to 75%, two days to 70%, three days to 65%, etc). Deliver to C213 (slot

in door). Be sure to keep a copy as "lost" essays will receive

a grade of zero. Hard copies must be submitted. Essays emailed to the instructor will

not be accepted.

Please Note:

1. Consumption of food in

class is a distraction and an annoyance to both other students and the

instructor; snack before or after, but not during class time.

2. Please ensure that

cell phones, pagers, blackberries, smartphones, etc.,

are turned off before entering the classroom.

3. If you arrive late for

class, do not enter until the break. My voice is loud: you can hear from the

hall without disrupting the class by entering.

4. Use of computers in

class is forbidden unless you have a documented disability requiring this.

5. This is a 4th year level Glendon/York course. Only students registered in 3rd

or 4th year or graduate students are permitted to enroll. Your work

will be evaluated at the 4th year level.

Essay Information

(prepared for another course but applicable to this one)

First Term.

We begin with a chronological and critical survey of Freudian theory tracing its development from its pre-psychoanalytic beginnings (up to 1897), through the psychology of the unconscious, so-called "id psychology" (1897-1914) and, finally, through the evolution of Freudian "ego psychology" (1914-1939). We then turn to Melanie Klein's contribution, her evolution of what might be called Kleinian Freudian theory. In addition to the writings by Freud and Klein, Caper's Immaterial Facts provides an excellent overview of both Freudian and Kleinian thought. An appreciation and critique of psychoanalytic theory is offered by Carveth (2013).

First Term Test

Here is a list of CONCEPTS from which

those that will appear on the first term test will be selected. This is not a

final list; a week or so prior to the test some concepts may be added or

removed. Additional Kleinian CONCEPTS.

Second Term.

We begin with Freud’s group psychology and then turn

to Bion’s group psychology. Read Golding’s Lord of the Flies or view

the British or American film versions of the novel.

Then we review of Freud’s developing theory of

religion:

Freud's five main

statements regarding religion:

(1) "Obsessive Acts and Religious

Practices" (1907). S.E., 9.

(2) "Totem and Taboo" (1913

[1912-13]), S.E., 13. Both (1)

and (2) are also in Freud, The Origins of Religion, (London: Penguin

Books, 1990), pp. 31-41; 49-224.

(3) "The Future of An Illusion"

(1927c), S.E., 21. You may use

the edition online here:

The

Future of an Illusion

(4) "Civilization and Its

Discontents" (1930a), S.E., 21. Both (3) and (4)

are also in Freud, Civilization, Society and Religion. (London: Penguin

Books, 1990), pp. 179-241; 243-340. Online here: Civilization and Its

Discontents

(5) "Moses and Monotheism" (1939), S.E.,

23; also in Freud, The Origins of Religion, pp. 239-386.

Of these 5 readings, we will go through Future and Civilization chapter by chapter.

Subsequently we turn to Showalter’s (1997) Hystories: Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Media

which should be purchased as we will go through it chapter by chapter. In

connection with Showalter we will also view the film Safe (1995) and read Carveth, D.L. &

Jean Hantman Carveth

(2003), "Fugitives From Guilt: Postmodern De-Moralization and the New

Hysterias,” American Imago 60, 4 (Winter 2003): 445-480. Online here:

Fugitives

Second Term

Test:

List of second term CONCEPTS from which 5 will be chosen to appear on the test.

Home | Publications | Reviews | Practice | Courses | Psychoanalysis | Existentialism | Religion | Links