Introduction to Archaeology

and Palaeoanthropology:

Introduction to Archaeology

and Palaeoanthropology:

Introduction to Archaeology

and Palaeoanthropology:

Introduction to Archaeology

and Palaeoanthropology:

Humanity's Journeys

Dr. Kathryn Denning

Anth 2140, Sept 2006 - Apr 2007

21 Nov 2006... Welcome!

Plan for class

1) Announcements

2) Hominid evolution: Review... and on to Neanderthals and Anatomically Modern Humans

Announcements:

Tomorrow in tutorial: Review and studying skull casts

Reading assignment for next week - no new reading. Consolidate and review!

Next week in lecture (28th): A little more about Neanderthals and modern humans.

After tomorrow (Nov 23), no more tutorials until January.

Quiz 3 will be held in lecture on Tues November 28.

And from last week's tutorial...

Why the public fascination with the Neandertals?

And what should we be looking for in representations of early people... if we want to analyze those representations anthropologically?

The Neanderthals... and their Disappearance

: (

Three things going on at once... or four!

Early Archaic Homo sapiens more developed than H. erectus, but clearly transitional - 400 000 to 125 000 BP? dates vary. Widespread throughout Africa, Asia, Europe. Gave rise to both us and and the Neanderthals

-Neandertals - essentially a form of late Archaic H. s. - 200 000? or conventionally, 130 000 to around 30 000 BP (maybe later), only in Europe and Middle East

Anatomically modern Homo sapiens sapiens – which is what we are – emerged in the Pleistocene epoch, maybe as early as 200 000, but definitely by around 120 000 bp.

n.b. it looks now as though we have very late H. erectus survivals too (H. floresiensis)

(Anatomically modern H.s.s. is defined by cranial architecture, lack of skeletal robusticity)

Images of Skulls only:

http://www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/humanorigins/ha/nead_sap_comp.html

Quicktime: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/neanderthals/skulls.html

(Consider: Why did species branch out when they did?)

What happened next???

The Neanderthals disappeared (more shortly), leaving just us... (and H. floresiensis).

But how did Anatomically Modern Humans -- us, the modern form of the human species that dates back 100 kyr or more -- emerge?

Three theories:

All believe that Homo erectus was the first human species to spread out from Africa... and that modern humans are all one species, Homo sapiens sapiens. The data we have are clear about this. But what exactly happened in between?

There are lots of 'transitional fossils', but the challenge is making sense of the pattern of them, throughout the Old World.

Multiregional Model (p 164): Homo erectus spread out from Africa, and each regional population evolved into Homo sapiens sapiens.

Recent African Origin Model / Out of Africa-2 (p 165): Homo erectus spread out from Africa. Homo sapiens sapiens evolved in Africa and then spread out over the same territory that Homo erectus had previously occupied -- replacing them.

Assimilation model ( p 167): Homo sapiens sapiens evolved in Africa and then spread out over the same territory that Homo erectus had occupied -- but there was some interbreeding.

BACK to the NEANDERTHALS

Optional: Examine skulls and skeletons of H.s.n. and H.s.s.: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/neanderthals/skulls.html, http://www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/humanorigins/ha/neand.htm, http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/N/neanderthal/facts/looked_like.html, http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99993555, http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/cavemen/chronology/contentpage5.shtml

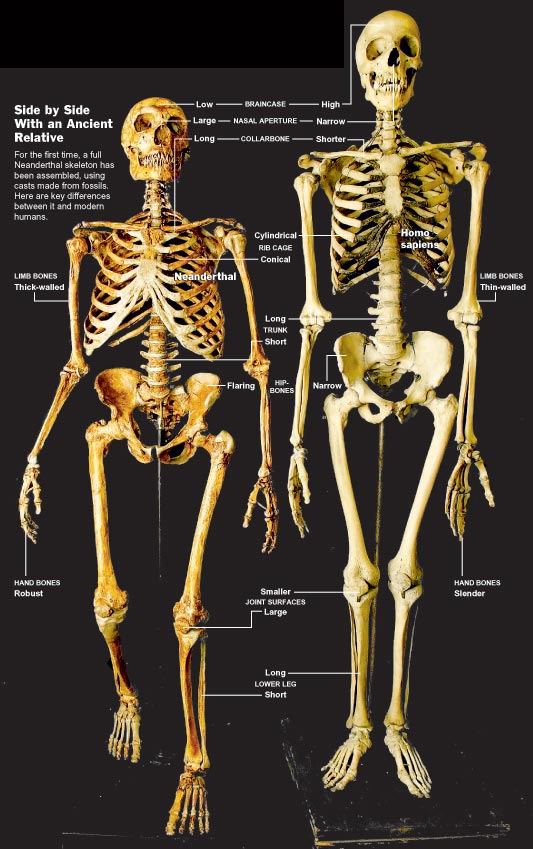

List of traits for Neanderthals (p 153)

- low sloping forehead (relative to moderns)

- large cranial capacity (1330-1750 cc)

- occipital 'bun"

- large, 'pulled-out' (prognathic) face

- large/projecting nasal opening, probably large nose

- large and rugged mandible

- no chin

- retromolar space

- Horizontal-Oval mandibular foramen

- relatively large incisors, relatively small molars

- taurodont molars (large pulp cavities, short roots)

- large, barrel-shaped rib cage

- long bones that are thick, somewhat curved, and rugged for muscle attachment

Versus list of traits for Anatomically Modern Humans (159)

- rounded head with large cranial capacity (1200-1700 cc)

- high forehead and bulging parietals (skull is widest at the top)

- round occipital

- small, somewhat flat, narrow face

- small eye sockets

- relatively small brow ridges, always divided in the middle

- small nasal opening and likely small external nose

- pronounced chin with one or two bony 'points'

- small teeth

- light postcranial skeleton and smooth long bones

So what do we actually know about the Neanderthal people?

Examples of Actual Neanderthal Skeletal remains

Neandertal: Original find,

1856, was amazingly controversial and very influential in later perceptions of

the Neandertal people. (First reconstruction based upon La Chapelle, an older

male suffering from severe arthritis.) Walked completely upright, looked much

like modern humans, actually had bigger brains than us, had sloping foreheads,

large brow ridges, large jaws, minimal chins. Lived throughout Europe, SW Asia,

and Central Asia.

Neandertal: Original find,

1856, was amazingly controversial and very influential in later perceptions of

the Neandertal people. (First reconstruction based upon La Chapelle, an older

male suffering from severe arthritis.) Walked completely upright, looked much

like modern humans, actually had bigger brains than us, had sloping foreheads,

large brow ridges, large jaws, minimal chins. Lived throughout Europe, SW Asia,

and Central Asia.

La Chapelle au Saints

Shanidar.

Several specimens: http://www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/humanorigins/ha/neand.htm

More specimens: http://www.msu.edu/~heslipst/contents/ANP440/neanderthalensis.htm

We know

- their morphology and its changes over time

- some aspects of their behaviour

- some of their material culture

- some of their dwelling sites

The current state of debate about the Neandertals

Our Relationship To Them

- war? mating/merging? resource competition?

DNA- suggests we didn't interbreed

Morphology - potential hybrid skeleton suggests we interbred (if so, how common was this? were the hybrids fertile? did the genes end up represented in later populations, or were they swamped?)

But consider: What if different things occurred in different places?

NOTE -- it will take a while for all this to settle down and for the best theory to win. But that's normal in science. Compare to understandings of electricity, telephones, etc.... It's incremental, doesn't occur all at once.

Capabilities

- did they have our intellectual capacity for innovation and adaptation? (some say yes, some say no) (Mousterian tools are fairly conservative in design, not changing much)

- new research indicates that there is not only evidence for ritual behaviour (burials), but also art... which is a surprise to some

- what about language? there is no doubt that they communicated, but what about?

- sociality - survival of the injured indicates care and compassion... or does it?

And what, historically and in popular culture, have we thought about the Neanderthal?

Neandertal: Original find,

1856, was amazingly controversial and very influential in later perceptions of

the Neandertal people. (First reconstruction based upon La Chapelle, an older

male suffering from severe arthritis.)

Neandertal: Original find,

1856, was amazingly controversial and very influential in later perceptions of

the Neandertal people. (First reconstruction based upon La Chapelle, an older

male suffering from severe arthritis.)

La Chapelle au Saints

Archaeology scholars S. Moser and M. Wiber have examined reconstruction illustrations and have noticed several key themes.

- there are 'icons' which tend to be present in these images, signifying primitivity and a separation from us: spears, clubs, skulls, long hair, etc.

- the relative positioning and activities of males, females, and children say a lot about perceived gender relationships in the past -- and in the present. (males tend to be the very 'Man the Hunter', are the ones with tools, weapons, are looking the most inventive, and are located centrally in the image)

Above: by Kupka, based on Boule, 1909

1928 reconstruction of Neanderthal

"Dissing the Neanderthal" in Chicago: http://129.237.227.3/explore/v1n2/neander1.html

Neanderthals as savage: http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/savage.html

Another great collage: http://www.mun.ca/biology/scarr/Neandertal_drawings.jpg

Zdenek Burian painting of Neanderthals. (mid 1900s)

Put a hat on a Neanderthal...

"The traditional earlier view of the Neanderthals as stooping 'ape-men' (which they were certainly not) was based largely on superstition and on the discovery of a few individuals with advanced bone disease at death. Carleton Coon's 1939 portrait of the Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal type individual in modern dress makes the point that artists' impressions depend very much on superficial things like dress and haircut." - http://www.orc.soton.ac.uk/view/402/

Channel 4, UK, recent series on Neanderthals

2001. Neanderthal child, computerized reconstruction.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/neanderthals/prod_03.html

Further information on Neandertals

There are many great books available on the Neandertals.

Also:

Summary: http://anthro.palomar.edu/homo2/neandertal.htm

Some recent articles:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4251299.stm

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/03/0306_030306_neanderthal.html

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4251299.stm

Examine skulls and skeletons of H.s.n. and H.s.s.: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/neanderthals/skulls.html, http://www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/humanorigins/ha/neand.htm, http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/N/neanderthal/facts/looked_like.html, http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99993555, http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/cavemen/chronology/contentpage5.shtml

Conflict and care: http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=00037FE6-1048-1CD0-B4A8809EC588EEDF

An argument (and there are others against this view) for replacement: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/03/0306_030306_neanderthal.html

A history of Neandertal... stamps!? http://www.franadams.com/exhibits/neandtal/neanxhbt.html

Hint: when looking for stuff on H.s.n., always search with "Neanderthal" and "Neandertal". The spellings are both correct, and are used somewhat interchangeably.

--------------

From Nature: Published online: 10 September 2002

Palaeontologists strike gold in nineteenth-century rubbish.

|

You wait the best part

of a century for a lost Neanderthal skeleton to be rediscovered, and then two

come along in a week.

Palaeontologists working in the German valley

that gave Neanderthals their name have found the remains of human skeletons,

their tools and the animals that lived alongside them1.

The bones were dug up for the first time, and subsequently discarded, nearly 150

years ago. The finding follows the Neanderthal baby recently found in a French

museum 90 years after its excavation2.

In 1856, quarry workers unearthed the first ever

Neanderthal bones in a cave on the side of the Neander valley, near Düsseldorf.

The larger bones were kept, but the rest of the cave's contents were thrown into

the valley floor 20 metres below.

By the time the bones were recognized as early

human, several weeks later, the cave had been quarried away and the other

fragments buried.

Palaeontologist Fred Smith of the Loyola

University of Chicago and his colleagues used historical records to work out

where the cave's contents might have fallen.

After picking their spot, and digging down for

four metres, they struck bone. One of the first fragments unearthed fitted onto

the thigh bone of the original Neanderthal. "It's little short of miraculous,"

says Smith.

The team now has about 75 fragments. They have

found pieces of the first skeleton's skull, plus remains from at least two

previously unknown individuals.

Carbon dating reveals that the newly found

Neanderthals lived during the Ice Age, about 40,000 years ago - around the same

time as the first skeleton. Neanderthals are thought to have arrived in Europe

about 120,000 years ago, and died out 90,000 years later.

But DNA from the new specimens hints that they

might be more closely related to Neanderthals from eastern Europe than to their

German neighbour. Too few skeletons have been analysed to be sure, says Smith,

but it is possible that Neanderthals travelled long distances.

In context

Smith's team also found stone tools, and bones

of other animals from the same period. These are the most exciting aspect of the

discovery, says archaeologist Clive Gamble of the University of Southampton, UK.

The first Neanderthal "had always been a

floating fossil - it lacked a context", says Gamble. The new evidence grounds

him in the bigger picture of what we now know about Neanderthals.

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

If the tools had been

found in 1856, Neanderthal man might have got a friendlier reception. Many

people refused to believe that the bones were old - this was before Darwin's

Origin of Species was published, after all. Some thought that the skeleton

belonged to a Russian soldier killed in the Napoleonic wars.

"Those arguments would have been invalid before

they'd been made," says Smith. "The early history of human palaeontology might

have been very different."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

|

|

|

|