Physics Research

"If I knew what I was doing, it wouldn't be research."

- D.M. Winnicott

Presently I Am Concentrating On:

Testing Fundamental Symmetries with Trapped Antihydrogen

A primary reason for making measurements with antimatter is to try to find

clues to one of the central mysteries of our time - namely, "Where is all the

antimatter?" That is, in the Big Bang, matter and antimatter were created in

equal amounts but the universe is now dominated by matter. This is a good thing

as matter and antimatter annihilate each other so we wouldn't be around if this

wasn't the case. But it still begs the question as to the mechanism that led to

the disappearance of the primordial antimatter. You can hear me talk about this

on the "Big Questions"

Quirks & Quarks show broadcast June 21, 2014 as well as my

"the star spot" podcast

Where Have All the Antimatter Gone? broadcast on June 15, 2014.

A few years ago I also gave a

public lecture

about this using as a central theme the movie "Angels & Demons" where antimatter is

used as bomb (trailer alert: not possible, so relax).

By the way, while there isn't a lot of it,

it is still true that there is antimatter all around us - even coming from

you ... and

bananas! A nice discussion of antimatter is given in

Ten things you might not know about antimatter (April, 2015) although,

come on, admit it, you know at least 5 of them.

The

ALPHA

(Antihydrogen Laser PHysics Apparatus) experiment

(

animation) is done

at CERN's

Antiproton Decelerator. The AD has been upgraded with a

new deceleration ring ELENA which is to come online in 2021

(LS2 Report: waiting for antiprotons... - CERN News, October,

2020). ALPHA managed to produce and hold ("trap")

antihydrogen atoms for as long as 1000s (2011), made the

first measurment of

microwave transitions in antihydrogen (2012), and measured

the charge of

antihydrogen (2014). The Canadian group on ALPHA was

awarded the 2013 NSERC Polanyi Prize.

Not to toot our own horn or anything but in 2010 ALPHA along with another AD experiment

called ASACUSA were named the

Physics World

Breakthrough of the Year. We were one of the

finalists for the 2021 Breakthrough of the Year but ultimately

Quantum entanglement of two macroscopic objects is the Physics World 2021 Breakthrough of the Year.

You win some, you lose some.

Spectroscopic Measurements with ALPHA

Spectral lines can be

measured with great precision. Comparing the spectral lines of antihydrogen

with those of hydrogen allows for one of the most precise tests of the

CPT Theorem (a kind of symmetry between matter and antimatter)

which requires the lines to be exactly the same.

CPT invariance is a fundamental requirement of

a quantum field theory and the Standard Model, the theory that describes the

interactions of elementary particles, is a quantum field theory. Finding

deviations from CPT invariance would have enormous implications for

physics and would require a rethink of our mathematical description of nature.

A clear, detailed discussion of testing CPT (and gravity, see below) using trapped

antihydrogen is given

in the 2015 PhD thesis by Andrea Capra.

Here are some recent results:

|

We're on the cover of Nature!

|

- Laser cooling of antihydrogen atoms

- nature, April 1, 2021

- Investigation of the fine structure

of antihydrogen - nature, February, 2020

- Observation of the 1S-2P Lyman-alpha

transition in antihydrogen - nature, August, 2018

- Characterization of the 1S-2S

transition in antihydrogen - nature, April, 2018

- Observation of the

hyperfine spectrum of antihydrogen - nature, August, 2017

- Observation of the 1S-2S transition

in trapped antihydrogen - nature, December, 2016

- An improved limit on the charge

of antihydrogen from stochastic acceleration - nature, January, 2016

Testing Gravity with ALPHA-g

I am also involved with the efforts to use trapped antihydrogen to test the

gravitational interaction between matter and antimatter (so-called "antigravity").

I wrote a little paper in 2012 -

"Why We Already Know that

Antihydrogen is Almost Certainly NOT Going to Fall "Up"" -

where I argued that it is probably

not much different from the matter-matter gravitational interaction but there is

still wiggle room and, as always, it is an experimental question! As said

by Shel Silverstein in his poem "Falling Up"

I tripped on my shoelace

And I fell up -

Up to the roof tops,

Up over the town,

Up past the tree tops,

Up over the mountains,

Up where the colors

Blend into sounds.

But it got me so dizzy

When I looked all around,

I got sick to my stomach

And I threw down.

ALPHA published a

first, very imprecise limit

on the difference in 2013. We are presently designing an optimized experiment (ALPHA-g)

to probe this fundamental question. Here are some recent articles about ALPHA-g:

You can watch Timelapse videos

of the construction in 2018 of the ALPHA-g apparatus in the ALPHA pit. It's

really amazing how the pit got filled up with stuff!

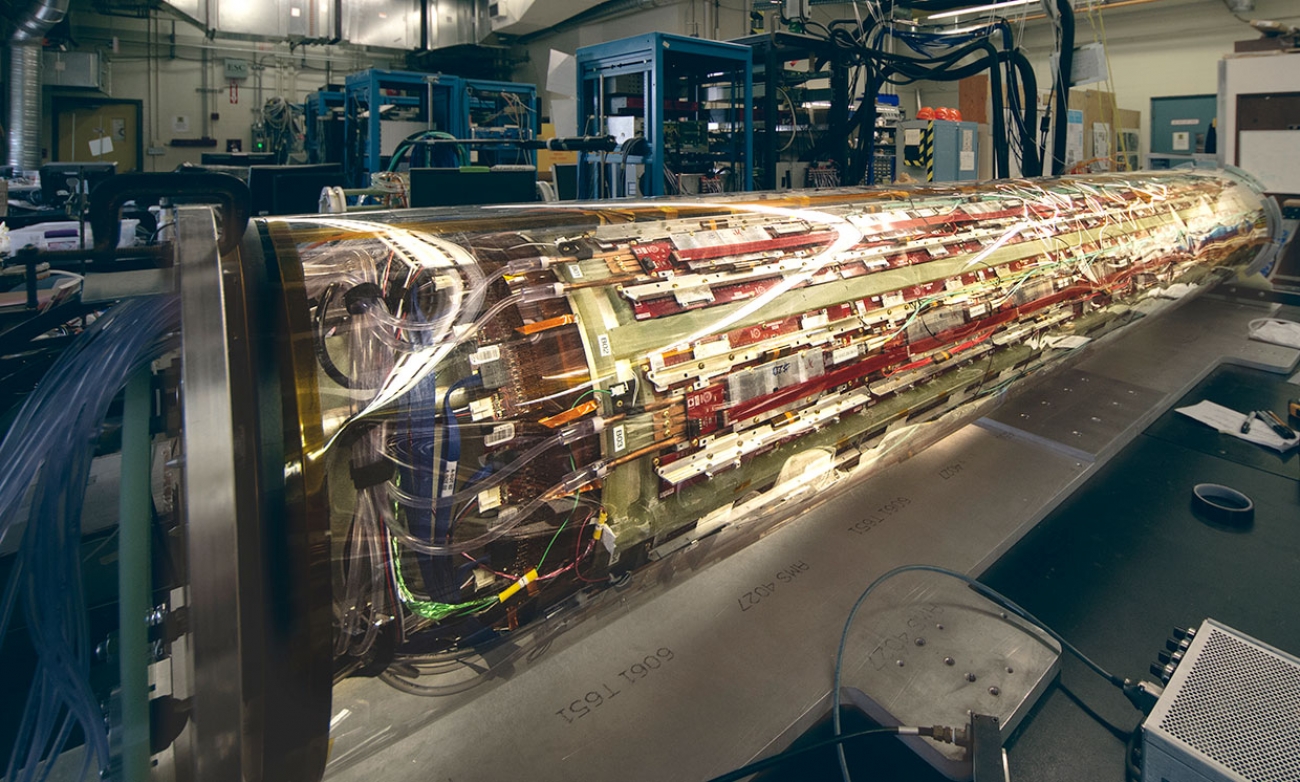

The part of ALPHA-g that I specifically work on is antihydrogen detection using a tracking chamber (a so-called

radial Time Projection Chamber or rTPC) and a scintillating cosmic ray veto detector. Here is some information

about the rTPC:

Long-baseline Neutrino Experiments using Liquid Argon Time Projection Chambers (LArTPC)

Muon Colliders

- One large advantage of lepton colliders such as the e+e- colliders LEP and SuperKEKB over

hadron colliders like the proton-proton collider LHC is that all of the beam energy goes into the primary

collision. That is, in a 91 GeV per beam collider like LEP, there is 182 GeV of energy available for new particle

production since the collision is a point-particle on point-particle collision. At the LHC, on the other hand,

the protons may have a kinetic energy of 7 TeV or so but the proton is not a point-particle and so that energy

is shared among the constituents of the proton, the quarks and gluons. The actual point-particle collisions

(the so-called "hard collision") are between constituents of the colliding protons and so the energy available

for production of new particles is often considerably less than 14 TeV. Why not then just build a 14 TeV center-of-mass

energy e+e- collider you ask? The answer is synchrotron radiation, the EM radiation emitted

by charged particles when they are accelerated (as happens for a charged particle travelling in a circular path

as in a collider). The problem is that for a given kinetic energy and accelerator radius,

the power (energy/time) of the emitted radiation

is inversely proportional to the 4th power of the mass of the particle being accelerated. Since the

proton is around 2000 times as massive as the electron, then amount of synchrotron radiation emitted for an electron

is 20004 times greater than for a proton. You can reduce this loss by increasing the radius but it

puts a major limit on e+e- colliders and is the reason why LEP basically set the energy

limit for circular colliders while the LHC uses the same tunnel but has beams with almost 100 times the energy.

- One could get around this to some extent (i.e., have the advantages of leptonic point-particle collisions but

with much less synchrotron radiation loss) if there were a heavier lepton than the electron. Luckily there is - the

muon. I have for many years (as in several decades) thought that muon colliders were the way to go. Oddly enough

there are few other crazy souls out there as well as evidenced by this November 2021 article from APS News -

Muon Colliders Hold a Key to Unraveling New Physics. And the nice thing is that with a

muon collider you also get a Neutrino Factory essentially for free. A Neutrino Factory was historically seen

as a precursor to a Muon Collider since you don't need two (colliding beams) but just one. Here's a small sample

of the various design reports, etc., over the years:

Past Experimental Collaborations:

[Menary Home Page]

[Particle Physics Resources]

[Physics & Astronomy]

[Graduate Program]

[York University]