Dispatch by Elaine Coburn

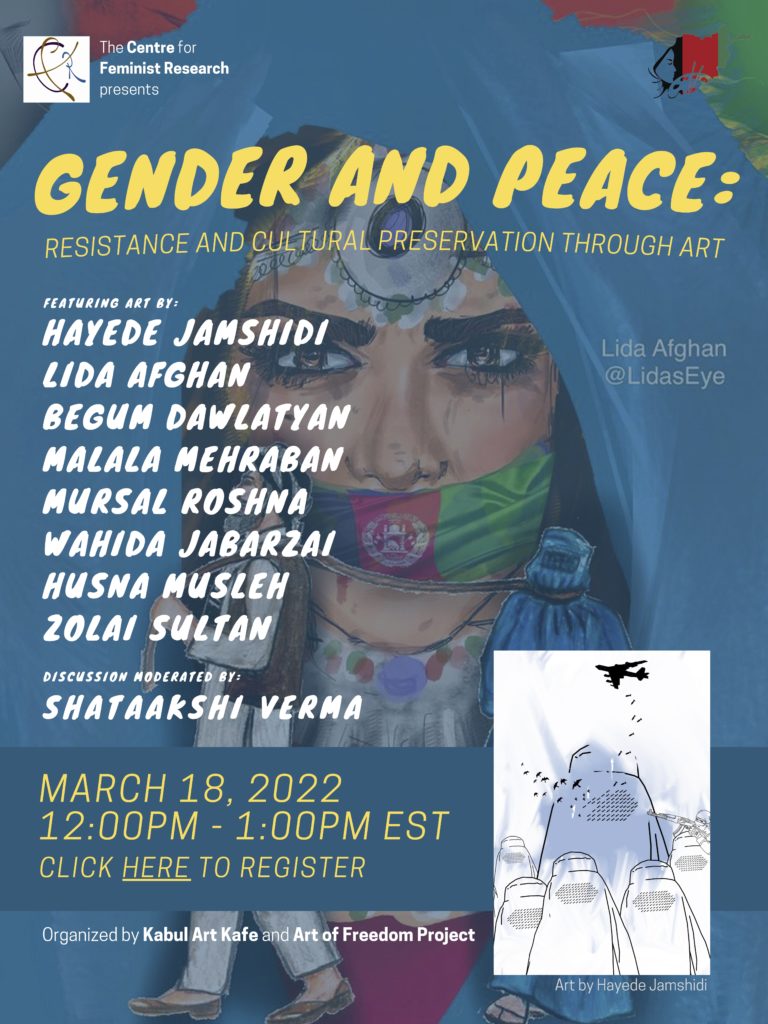

The Centre for Feminist Research is pleased to support the work of Afghan women artists in collaboration with the Art of Freedom Project, supported by the British Council, and the Kabul Art Kafe.

Amidst ongoing conflict, violence, suffering, and exile, these young women are using their imaginations to face the pain of the past and the injustices of the present. But their work does not stop there. Instead, they demand a more peaceful and more just world for each woman and for all women — especially Afghan women still living in conflict zones.

The event from which these remarks are drawn was held on March 18, 2022 and the discussion was chaired by Shataakshi Verma. Verma is a development professional working in the field of human rights, gender labour policy, peace and conflict and livelihood strengthening. She has worked in India, Afghanistan and other South Asian countries on conflict and peace-building through advocacy and art.

Lida Afghan My artwork focuses on the beauty of Afghanistan and, especially, Afghan women. I have grown up in exile and travelled to Afghanistan for the first time in 2015. I was terrified before I left, because in the media, I only saw images of conflict. The reality was very different from what I had imagined — the country and the people were so beautiful and so mesmerizing. When I went back to Denmark, I tried to explain what I had seen, but there, too, people had only seen Afghanistan in the news and they could only imagine violence. This is why, in my artwork, I show Afghanistan in the way I experienced it in 2015, creating images that show our colourful culture, our caring people. I became passionate about using art for a bigger purpose: to raise awareness. My artworks show women who have suffered, but who are strong. Art is a universal language, so pick up your paintbrush!

Hayede Jamshidi When I was about three or four years old, my parents and family took refuge in Iran. I left with just a few memories of Afghanistan, but in our family we speak in Dari and we wear our traditional dress, and so my connections with my motherland has not been severed; they remain. In Iran, I have experienced racism, but I try and challenge this by making people aware of what is happening in Afghanistan. I enjoy collages and illustration, but I also use new software and computer techniques to create science fiction. In my artworks, I imagine human beings in new environments and ask what the relationship is between ourselves and our environment and how we change in new environments. I used to pray that God would bring the bird of peace and freedom to our land, but maybe this bird was killed and will never come back. Some of my work explores how war changes and destroys the beauty in human beings, breaking them so you are no longer the person that you used to be. Our body, our mental state changes during war. It is important to think about our experiences as Afghan women, and about all those who are still living in and experiencing war.

Malala Mehraban In our artworks, we can use our voice to portray pain but also to call for hope. I began drawing and painting in Glasgow, Scotland. I missed Afghanistan, so my artworks were a way of bringing back good memories. I began with still life and portraits, as a young artist just beginning in art school, and then, once in Canada at the Ottawa School of the Arts, I learned much more about professional techniques. These new techniques expanded my style, including sculpture, which is now my favourite medium. I like to work with shadow, contrasts… I like to try everything!

My whole project is motivated by the right to education, specifically Afghan girl’s education — that is what we need, that is what will make a difference to our society, our community, our country. In one of my pieces, I show an Afghan girl writing, “I want to be a teacher," because it is a basic human right, to be educated. And I want to move beyond the destruction. There is destruction, that is true. But it is not the whole story, because we have many wise and educated women. It may seem so small to dream, to want to become a teacher, but I hope for it, I pray for it.

Husna Musleh. I am an Afghan Danish artist. I was born and raised in Denmark and I am 19 years old. My journey with art began in 2002, because that is when I was born — just after the 9/11 attacks on the United States a year earlier. These events had a huge, distorted effect on how people understood Afghani people. The Afghanistan I heard about was a terrible, violent place. But I would come home and taste the aromatic foods from my mother, the poetry recited and shared by my family, and the stories from home, and so I would experience a different Afghanistan. This is the Afghanistan that I try to share. The world can be too political, so I escape through my art. I try and show the rawness of the world, but most of all, I try and help people see the human behind the media images of Afghanistan. That is what I try and do. One of my paintings shows the courage and bravery that is required to feel hope. In my artwork, I thank my parents for all they have sacrificed. Parents want a bright future for their children, they do not want them to grow up in war, so there can be guilt for not being able to create that world, free of conflict, free of violence.

Mursal Roshna I left Kabul three months ago and I now live in Germany. In Afghanistan, there is no chance to take art classes. Women are not allowed to have an education or to work. I do not know how to talk about women, since we have learned that women have no identity of their own, no value. For men, what women feel is not important. Women cannot raise their voices or they will be beaten. Young boys can beat their mothers and their sisters. The woman must sacrifice her rights. I am trying to voice women’s pain, but also what we feel, what we want, what we hope.

Zolai Sultan I grew up in Afghanistan and I lived in Kabul until August 2021, when the Taliban took control. I am a self-taught artist, now living in Ireland. My family and myself have been through many difficulties, but now I am hoping for a brighter future. The Art of Freedom project helps me to express what is on my mind and on the minds of a thousand other girls like me. We create art pieces about gender and freedom. This is about women and their rights. I come from Afghanistan, so I know these women better than anyone — I was one of them. My artwork has a thousand meanings, but images include a girl with a sad face because girls have been banned from going to school. The Taliban will not allow her to go. Despite the sadness of her circumstances, the background represents her hopes and her wishes.

Wahida Jabarzai I was born in Afghanistan and I now live in London. My family has been very supportive of my art. Since expressing myself verbally is difficult for me, I like artworks as a way of expressing what I would like to say, if I could. Right now, I am concerned with art with a message, especially the contrast between the mainstream media and what we hear from our own families. Afghanistan is portrayed as backward, barbaric, and war-torn. Deaths and casualties are reported as if that was normal, just another statistic on the news. Too often, non-Afghans speak for Afghans and they desensitize people to our humanity. I want to take stories back so that we tell our own stories, ourselves. We refuse to see in black and white — we see Afghanistan in full colour. We are the ones who are going to empower our own people.