Interview by Serena Aprile

What was it like being the President and Vice Chancellor of York University in 1997-2007, a time when not many women were in such a position?

In my academic life, I studied at four different universities. For twenty years after my doctoral studies, I was a professor and administrator at the University of Toronto, then after eight years in the Senate of Canada, I was president of Wilfrid Laurier University (WLU) for five years from 1992-1997 and, finally, I was at York University from 1997-2007, and then taught for a few more years. All are interesting universities, each with its own culture and characteristics, but at York University I felt most at home. I love the edgier culture of York University, its total lack of complacency.

Our convocations are great moments of triumph for the graduands, faculty, staff, and families—joyful occasions!

When I took the presidency of WLU I was not the first Canadian female university president, and I received excellent advice from women colleagues who were or became presidents elsewhere. At York University, I followed another female president, a longtime friend, Susan Mann, who preceded me from 1992 to 1997. The presidency is unlike any other senior administrative position, and I was grateful for conversations with other presidents, women and men, who shared their experiences. I was fortunate because there were people who disagreed with my decisions or my leadership style, but as far as I could tell none of these disagreements was rooted in sexism.

"I love the edgier culture of York University, its total lack of complacency."

Lorna Marsden

After participating in the founding meeting, you later became the President of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC), from 1975-1977. What were the motivations for establishing the NAC, and how did you and the other early participants create the first-ever national association to support and promote the interests of women? What was it like being President of NAC, what were some of the satisfactions and challenges of this position?

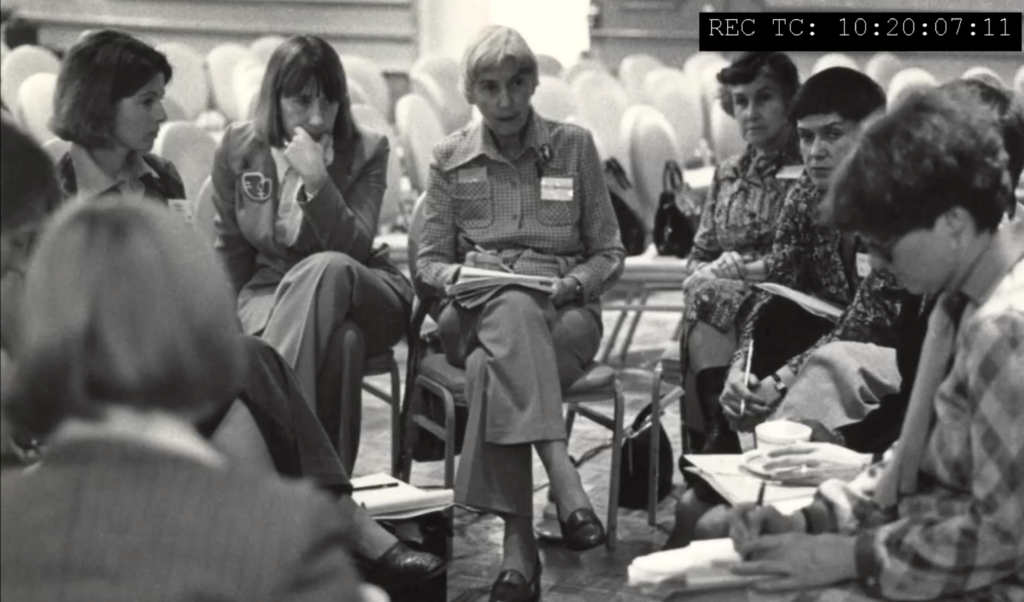

After the Report of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women (RCSW) was tabled in December 1970, feminists formed pressure groups to press for the implementation of the RCSW recommendations at both the provincial and federal levels. When I returned to Canada after completing my doctoral studies at Princeton University, I was asked to join the Ontario Committee on the Status of Women (OCSW). We were a group of like-minded women. Our aim was to ensure that recommendations of the Report concerning provincial laws and regulations (such as the gender wage gap) were implemented to help bring about greater equality for women. So, we lobbied and put pressure on many levels of government and especially the government of Bill Davis, the premier of Ontario from 1971-1985. It was hard work, but we had some successes; for instance after about seven years, the Davis government agreed to some form of pay equity. We supported many other feminist groups similarly committed to achieving equality for women. Our main strategy was to prepare well-researched documents, but we also found that one of the best ways of getting things done was through the different political parties. Our members included women in all the major parties.

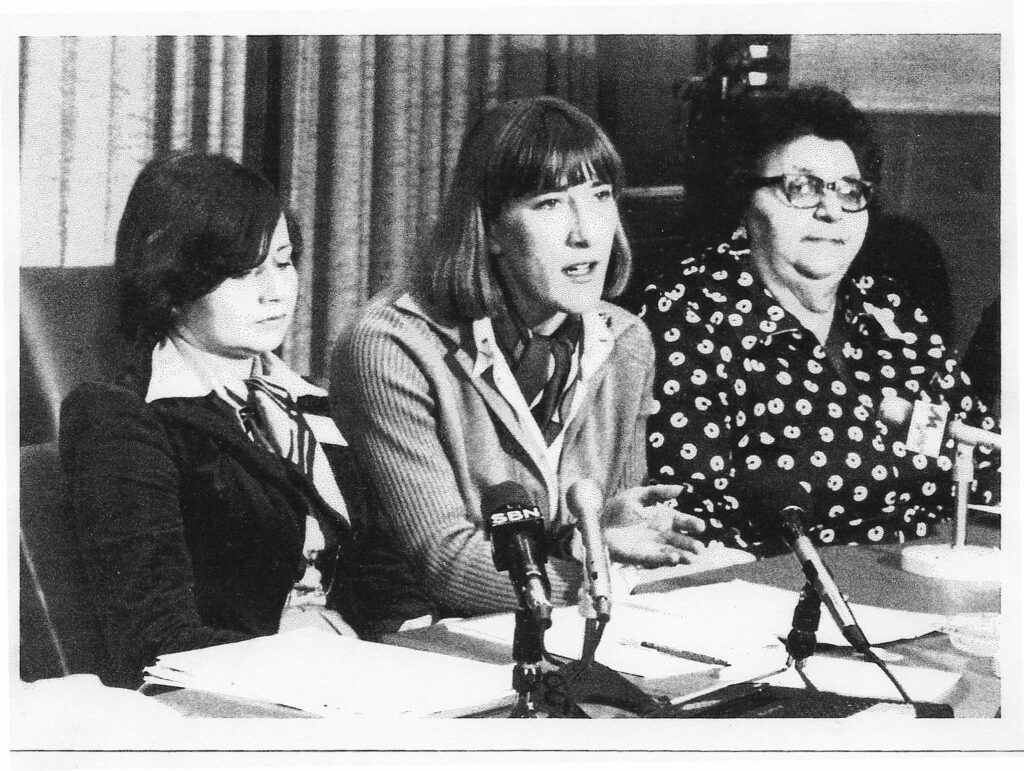

In April 1972, Laura Sabia, who had lobbied hard for the creation of the RCSW, convened the Strategy for Change conference to press for implementation of the recommendations. Women like Grace Hartman, Madeleine Parent, Mary Two-Axe Earley, and other leaders of women’s groups attended the founding meeting, as did most of us in the OCSW. That conference, in the old King Edward Hotel in Toronto, created the National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC).

NAC was a coalition of feminist groups from across the country organized to put pressure on the federal government so that they would implement the Report’s proposals. The OCSW was just one of those many groups from coast to coast focused on provincial governments. Laura Sabia, a well-known Canadian social activist and advocate for equality for women was the founding president; Grace Hartman, a union activist and the first female president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) the second; I was the third, although at the Founding Meeting, I was simply a novice learning the ropes.

Before modern-day electronic communication, organizing was difficult. There was a fine group of leaders from every province and territory, however, and we wrote to each other via the post and occasionally talked, being careful because long-distance telephone calls were very expensive. We lobbied hard with those people who could make change, such as our Members of Parliament, Senators and political party executives at both the federal and provincial levels.

"Being president of NAC was very challenging: it was time-consuming, filled with opposing views among the members, and no real funding at first."

Lorna Marsden

My innovation was to take the NAC representatives to a meeting with Cabinet members in Ottawa. That was a mixed success! Being president of NAC was very challenging: it was time consuming, filled with opposing views among the members, and no real funding at first. The OCSW, on the other hand, was differently organized, had constructive discussions, and worked strictly at the provincial level. Many of my closest friends then and now are from the OCSW.

She attended the founding meeting of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women in April, 1972 and served as President of NAC from 1975-77.She was active in the Ontario Committee on the Status of Women from 1971 and is co-author of the book about that feminist group, White Gloves Off (2018).

She joined the Liberal Party of Canada, becoming national policy chair in 1975 and vice-president in 1980. In 1984, she was appointed by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to the Senate representing the senatorial division of Toronto-Taddle Creek, Ontario. While serving on the senate, she chaired the Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology from 1989-1991 as well as being a member of committees ranging from National Finance to a special committee on Youth. She resigned in 1992 to become President and Vice-Chancellor of Wilfrid Laurier University. In 1997, she was appointed President and Vice-Chancellor of York University, serving until 2007.

Marsden was named one of "Canada's Most Powerful Women: Top 100", She became a Member of the [[Order of Canada]2006] and a member of the Order of Ontario in 2009. She received the Order of Merit (First Class) of the Federal Republic of Germany in 2007. She holds honorary doctorates from the University of New Brunswick, University of Winnipeg, Queen's University, the University of Toronto, Wilfrid Laurier University and the University of Victoria. She has received the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal, the Canada 125th Anniversary Medal, and the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal. She was named a YWCA Women of Distinction in 2003 and was made an Honorary Alumnae of the University of Victoria in 2003. She received the Senate Medal for Canada 150 in 2017.

As President of York University, Marsden founded the university's Culture and Communications program (joint with Ryerson University) and she led a major building campaign. One outcome of the building campaign was the construction of the university's first green building: for computer engineering.

Among your many publications, in your 2012 book Canadian Women and the Struggle for Equality you write about Canadian women’s journey, or journeys, fighting for equality for more than 150 years. Looking ahead, how does understanding the past help continue the fight for gender equality in our society today and into the future? What do you think young feminists should know and what advice would you give to us?

For many years at the University of Toronto and then later at York University, I taught courses about the labour force and women’s studies. Many students took the courses based on their ideological commitment to understanding and supporting women’s issues. But to understand how social change comes about in this complicated country, they need to understand the structural and cultural issues that either prevent or facilitate change. My 2012 book was intended for those undergraduate students, so each chapter is meant to illustrate some of those structural and cultural issues: for instance, the division of powers between the federal government and the provinces, and how history and economics define different interests in equality.

"All problems have historical roots that are important to understand when trying to make changes. I urge young feminists to analyze the issues they find crucial—and then look at the roots of that issue in history and in the social and economic structures."

Lorna Marsden

Each generation tends to think that their challenges are “unique,” but they seldom are. For example, in the ‘50s the number of women in the paid labour force was low, but many adult women worked before and after marriage, or if they were widowed or deserted (divorce was very difficult). They often faced laws and customs barring them from jobs. In my generation, many more of us said, “We're going to work in all occupations and regardless of marital status.” Where rules had to be changed to permit married women to work, such as teaching, we lobbied for change. We thought we faced new problems, but many women of the earlier generation had faced the challenges of working life, too. All problems have historical roots that are important to understand when trying to make changes.

I urge young feminists to analyze the issues they find crucial – and then look at the roots of that issue in history and in the social and economic structures. From that analysis, sort out how to tackle the problem. In my opinion, demonstrations are not the most effective way of creating change. Wasting your time and effort is an awful error. Life is too short for that! What you really need to do is get laws and regulations changed.

Sometimes you can get a change just by going and seeing the right people with a well-prepared brief. Proposing a constructive way forward, in a written document, like a policy or action brief, is usually the most effective way to dismantle barriers to women’s equality. One has to propose a workable solution to the system, and, in some cases, this demands personnel changes to really tackle important problems.

For women who don’t have access to decision makers or who have barriers to the resources to creating concrete, workable courses of action, it is important to find or found the right group who will do that work.

Serena Aprile is a third-year student at York University's Glendon Campus majoring in sociology and minoring in political science. She is interested in the impact of education especially for young women.