The following article by Faculty of Education PhD candidate Ixchel Bennett was originally posted in the February 24, 2021 issue of Policy Options Magazine as a part of the Identifying the Barriers to Racial Equality in Canada special feature.

Addressing racism in the classroom requires educators to ask hard questions of themselves, white discomfort, and the discarding of old traditions.

In 1920, Duncan Campbell Scott, then-deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs is quoted for suggesting that his goal was to “get rid of the Indian problem.” Scott’s solution was to expand the residential school system forcing Indigenous people to assimilate. One hundred years later, the legacy of residential schools continues to impact Canada’s current school systems. Research shows that Indigenous children across the country continue to experience systemic racism by their peers, teachers and the larger community. Needless to say, shaming and assimilation persist today.

Over the past 16 years, I’ve worked in education in various roles as a teacher, board lead, university course director and now as a vice-principal. Throughout this time, I’ve noted many advancements in championing Indigenous education and narrowing the Indigenous achievement gap by increasing graduation rates. But time and time again, I’ve also noticed deep discomfort and fear among educators when it comes to addressing anti-Indigenous and anti-Black racism in schools.

“I don’t feel comfortable!”

For the most part, educators want to have a positive effect on their students. But when asked to participate in creating that change by addressing racism, I’ve witnessed some who squirm and say they prefer not to “rock the boat.” For systemic racism to be dismantled in Canadian schools, however, we need to address the discomfort and fear that some educators feel in disrupting anti-Indigenous and anti-Black racism in schools.

For example, during a staff meeting at a Scarborough school where I previously worked, an administrator asked staff members how racism was being spread at school. Was it the curriculum? Our choices of books? The way we speak to students? I thought these were excellent questions to ask to encourage self-reflection and to prompt discussion about potential areas for improvement. In response, however, there was a long silence.

By comparison, I asked colleagues at different schools if race-related conversations were also happening during their staff meetings. For example, looking at race-based data and examining in-school practices that might hinder Black and Indigenous students. Most said yes, but added that they were led largely by Indigenous, Black and racialized educators.

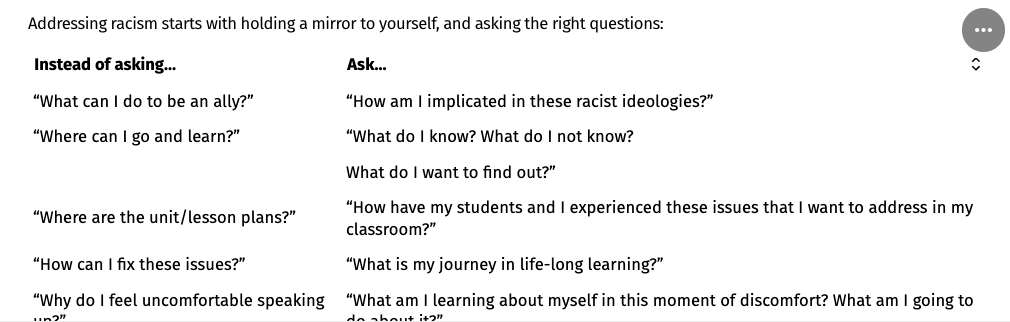

Why are some white educators so uncomfortable? Perhaps it’s fear that openly and honestly engaging in these critical conversations may result in being labelled “racist” or “insensitive.” That said, many racialized and white educators do want to speak up. They are on a journey towards unpacking their racist ideologies or internalized oppression – but they don’t know how and where to begin or what language to use. Sometimes, it helps if a critical friend engages them in discussion. But this responsibility usually falls on Indigenous, Black and racialized people, which is problematic because the work of becoming anti-racist is a personal journey that doesn’t involve others.

“ I do not feel safe”

This makes me wonder what the union’s role is in protecting racialized teachers from microaggressions and unintentionally or intentionally racist remarks. Whose safety matters when having these discussions? What role will the union play in dismantling racism at Canadian schools?I’ve witnessed colleagues respectfully correcting white educators for saying: “I do not think racism is that bad in our school…is it?” Unfortunately, some have complained to the teachers’ union that they “do not feel safe” or feel “attacked” whenever they’re corrected for making a racist or problematic statement.

There’s also significant discomfort among educators when it comes to using anti-racist language when teaching elementary students. I’ve consistently heard some say that children at this age have “tender minds” or are “too young” to learn, and that “we don’t want to instill fear” in them. Yet research suggests that kids begin to perceive racist ideologies from the age of two. That’s why anti-racist education shouldn’t be just one lesson or unit plan. Instead, it needs to be embedded in everyday practices, starting from kindergarten. And if a student uses the term “racist” incorrectly, teachers should take that as a learning opportunity to address the class.

“I have good intentions!”

There is no doubt that educators have good intentions for student safety when participating in school board-wide events, such as Orange Shirt Day, Remembrance Day and Treaty Week. But what happens when these events cause harm to students?

For example, the purpose of Orange Shirt Day is for educators to teach students about the cultural genocide committed against First Nations, Métis and Inuit children, so it’s an opportunity for the school community to unite in the spirit of reconciliation. Specifically, students learn that the RCMP forcefully removed Indigenous children from their families and communities, as the Canadian government’s goal was to “kill the Indian in the child.”

That’s why, on Sept. 30, they read about Phyllis, a residential school survivor from Northern Secwpemc in British Columbia. As the story goes, Phyllis’ grandmother bought her an orange shirt to wear to St. Joseph’s residential school, but when she arrived, school officials took her shirt away. As a 6-year-old, Phyllis expresses that she felt worthless and like no one cared about her.

Despite this focus on Phyllis and other Indigenous residential school survivors, though, their experiences are often decentered on Orange Shirt Day. How? I’ve seen students receive handouts with the sentence starter, “I matter because…” Students’ responses, which ranged from “I am lucky I have a safe school” to “I have a mom and a dad,” are all valid but the voices of Indigenous people are erased in the process. It’s essential that educators focus on Phyllis’ story because only then can Canadians move forward towards reconciliation. For example, educators can dive deeper into researching residential schools’ objectives, and then explain how they were wrongly informed by white supremacist ideologies.

Another board practice we need to reimagine is “spirit days” like Crazy Hair Day, which can be problematic if students choose to wear an Afro, cornrows or Native long braids as a costume. Students also learn that this type of hairstyle is “crazy,” which dehumanizes Indigenous and Black people for the sake of “making school fun” or “keeping old traditions.” What’s more, Sikh and Muslim students can’t participate in these activities because some wear a turban or hijab, so they’re automatically excluded.

Educators need to understand that some school traditions promote racism, sexism, classism and other forms of discrimination against marginalized groups. We can no longer say, “But we’ve always done it this way” or “It’s a school tradition.” For example, hold a spirit day when students identify acts of kindness among their peers and compliment them, or wear their favourite piece of clothing and share why it’s special to them. This would enable students to participate without having to assimilate or adhere to antiquated norms.

It’s time to involve students in critically rethinking past practices and reimagining new inclusive school traditions. Educators can no longer hide behind fear when Indigenous, Black and racialized students’ lives depend on it.

Ixchel Bennett Ixchel Bennett is Indigenous Nahua/Zapoteca from Mexico. She is a vice-principal with Toronto District School Board in a school with a high population of Indigenous students. She is also a PhD Candidate with York University’s first Indigenous PhD cohort.