Culturally Relevant and Anti-Racist Leadership

How do we imagine and rebuild an education system that is relevant and responsive to the communities that we serve through centring the experiences, knowledge systems, and leadership approaches of the global majority?

Eurocentric values and worldviews dominate schooling and educational leadership, which have resulted in instructional, transformational, and transactional leadership models that fail to disrupt historical and enduring patterns of oppression and inequity in schools (Khalifa et al., 2016). In schooling contexts where there are disparities and disproportionality in student achievement, well-being, and engagement, culturally responsive leadership can result in socially just and equitable outcomes for all learners (Gooden & Dantley, 2012; Horsford, 2011; Khalifa, 2012; Santamaría, 2014). Following similar frameworks as culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995) and culturally responsive pedagogy (Gay, 2002), culturally relevant and responsive leadership is critical in creating a school climate that serves all learners and centers the voices of historically oppressed communities. Culture is defined here broadly to include multiple, intersecting and fluid identities such as race, gender, social class, gender identity, faith, sexuality, dis/ability, language, accent, place of birth, immigration status, and more.

In their literature review, Khalifa et al. (2016) identify four major strands of culturally responsive school leadership: critical self-awareness, developing culturally responsive curricula and educators, developing and sustaining culturally responsive and inclusive school environments, and engaging students and parents in community contexts. This requires resisting oppressive approaches to schooling and leadership, such as challenging deficit thinking about historically oppressed children and families (Khalifa et al., 2016; Shah et al., 2022). Culturally responsive leaders ensure that pedagogies are relevant to and reflective of the student body. Leaders must also be able to attract and retain staff who embody anti-oppressive, culturally relevant, and culturally responsive practices. Vidya Shah, in the podcast, “Reimagining Indigenous, Black and racialized leadership within the nonprofit sector” shares that collective and intergenerational leadership that is grounded in a network of relationships, asks responsive leaders to continuously develop their capacity to love so that they can actively disrupt the status quo (Msosa & Dogra, 2022). In their work, Shah et al., (2022) assert that “while it is important for leaders to represent the racial diversity of students and families, it is as, if not more important for leaders to have anti-racist orientations” (p. 465).

Horsford et al., (2011) speak to four dimensions of culturally relevant leadership. The political context requires an understanding of the ideological and historical origins of practices, policies, and patterns in education. The pedagogical approach requires the development of pedagogy that centers cultural awareness of how identity shapes what we teach, how we teach, and how students learn. The personal journey requires engaging in reflective practice, while professional duty dimension requires leaders to uphold equity and justice-oriented standards and competencies and make these practices a reality in schools. Drawing on Beachum’s (2011) concept of culturally responsive leadership, Lopez (2016) also names the importance of learning to unlearn, engaging agency and social action, and creating avenues for personal support and sustenance. Thus, culturally responsive and relevant leaders acknowledge and disrupt oppressive systems to affirm the identities of students and families on the margins, and anti-racist leaders see “this work as larger imperative to the larger generational goal of racial justice” (Shah et al., 2023, p. 24).

Race, racism, and racialization are often underexplored identities and oppressions, so we turn our attention to concepts of race evasion and the myth of neutrality (Shah et al, 2022). Critical Race Theory asserts that racism is a normal, everyday experience for people racialized non-White (Delgado & Stefanic, 2001) that is built into systems and structures that perpetuate ongoing racial inequality and white domination (Bonilla-Silva, 2001). Allen and Liou (2018) assert that leadership should begin with the premise that White supremacy is part of a hidden curriculum that is entrenched in schools. As such, leaders’ consciousness of racialization impacts their understandings and practices of leadership for freedom and liberation (Agosto & Roland, 2018; Santamaria, 2014; Shah, 2018). For example, instead of investing time and energy into making “white spaces'' available and accessible to racialized learners and leaders, thereby reinforcing white supremacy, Radd and Grossland (2019) argue for a restructuring of the system that makes whiteness visible. Being anti-racist leaders also means that leaders must continuously engage in reflection and invest time in healing their own racialized trauma so as not to replicate whiteness and resist being complicit in upholding white supremacy (Shah et al., 2023; BIPOC Leadership Energies, 2024).

Connected to Critical Race Theory is Critical Whiteness Studies, which explores the ways in which whiteness is invisibilized and normalized in everyday operations and interactions. We draw on Gillborn’s (2015) definition of whiteness as “a set of assumptions, beliefs and practices that place the interests and perspectives of white people at the center of what is considered normal and everyday” (p. 278). Blackmore (2010) similarly names the normalized and invisibilized nature of whiteness and the subsequent resistance of white educators to confront racism. Toure and Dorsey (2018) assert that white leaders need to develop a white racial literacy that includes critical reflections and actions. For example, white leaders may reflect on and disrupt the ways in which silences, denials, projections, protections, punishments, stalling, and inaction maintain White power in the institution of schooling.

Reflection Questions:

- What does culturally relevant and responsive leadership and anti-racist leadership look like within the educational spaces that we take up?

- How might we create leadership practices that disrupt White supremacy in education?

- Who do we need to be as leaders to lead in culturally responsive and anti-racist ways?

- How might we apply this understanding to the work we do in communities, schools, and academies?

References

Allen, R.L. & Liou, D.D. (2019). Managing Whiteness: The Call for Educational Leadership to Breach the Contractual Expectations of White Supremacy. Urban Education. 54(5), 677-705.

Beachum, F. (2011). Culturally relevant leadership for complex 21st-century school contexts (2nd Ed.). In F.W. English (Ed.) The Sage handbook of educational leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

BIPOC Leadership Energies. (2024). Storying the report: A RiverJourney into BIPOC Leadership Energies. Toronto Neighbourhood Centres. https://neighbourhoodcentres.ca/bipoc.php

Blackmore, J. (2010). “The other within”: Race/gender disruptions to the professional learning of White educational leaders. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 13(1), 45–61.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2001). White supremacy and racism in the post-civil rights era. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053002003

Gillborn, D. (2015). Intersectionality, Critical Race Theory, and the primacy of racism: Race, class, gender, and disability in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), p. 277–287.

Gooden, M. A., & Dantley, M. (2012). Centering race in a framework for leadership preparation. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 7(2), 237-253.

Horsford, S. D. (2011). Learning in a burning house: Educational inequality, ideology, and (dis) integration. New York: Teachers College Press.

Horsford, S., Grossland, T., Gunn, K., (2011) Pedagogy of the personal and professional: Toward a framework for Culturally Relevant leadership. Journal of School Leadership, 21, 582-606.

Khalifa, M. (2012). A re-new-ed paradigm in successful urban school leadership principal as community leader. Educational Administration Quarterly (EAQ), 48(3), 424-467.

Khalifa, M. A., Gooden, M. A., & Davis, J. E. (2016). Culturally responsive school leadership: A synthesis of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1272–1311.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163320

Lopez, A. (2016). Culturally responsive and socially just leadership in diverse contexts: From theory to action. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Msosa, Y. & Dogra, K. (Host). (2022, June 15). Episode 9: Reimaging Indigenous, Black, and racialized leadership within the non-profit sector [Audio podcast episode]. In Digging in with ONN. Ontario Nonprofit Network. https://theonn.ca/podcast/episode-9-reimagining-indigenous-black-and-racialized-leadership-within-the-nonprofit-sector/

Radd, S.I., Grossland, T.J. (2019). Desirablizing whiteness: A discursive practice in social justice leadership that entrenches white supremacy. Urban Education, 54(5), 656-676.

Santamaría, L. J. (2014). Critical change for the greater good: Multicultural perception in educational leadership toward social justice and equity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(3), 347–391.

Shah. V. (2018). Leadership for social justice through the lens of self- identified, racially and other-privileged leaders. Journal of Global Citizenship and Equity, 6(1), 1-41.

Shah, V., Aoudeh, N., Cuglievan-Mindreau, G., & Flessa, J. (2023). Tempering Applied Critical Leadership: The Im/Possibilities of Leading for Racial Justice in School Districts. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(1), 179-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X221137877

Shah, V., Aoudeh, N., Cuglievan-Mindreau, G., & Flessa, J. (2022). Subverting Whiteness and Amplifying Anti-Racisms: Mid-Level District Leadership for Racial Justice. Journal of School Leadership. 32(5), 456- 487. https://doi.org/10.1177/10526846221095752

Toure, J., & Dorsey, D. T. (2018). Stereotypes, images, and inclination to discriminatory action: The White racial frame in the practice of school leadership. Teachers College Record, 120(2), 1-38.

Panelists

Melissa Wilson

Melissa Wilson has worked for Peel District School Board for more than a decade in several positions. Currently, Melissa is a vice-principal at Mayfield Secondary School. Prior to her current role, she was the coordinator of anti-Black racism education, the coordinator of Indigenous education, an equity resource teacher, and a classroom teacher. Melissa is a PhD candidate in the Social Justice Education Department at OISE, University of Toronto. She completed her MA in 2012 in Sociology and Equity Studies in Education at OISE. Her research interests include anti-racism and anti-colonial education, feminist theory and methodologies, and an epistemology of ignorance. Her current research analyzes equity work in the Ontario public education system.

Nora Hindy

Nora Hindy is Vice Principal with the Peel District School Board. She holds a Masters degree in Public Policy, Administration and Law, focusing her research on Islamophobia in Ontario public schools. As a Board of Director of Urban Alliance on Race Relations, Nora has worked with unions and advocacy groups to help bring the voices of marginalized communities to the forefront. As a community organizer, she co-founded NCCM’s Stronger Together campaign, a democratic engagement campaign aimed at ensuring legislation and policies are reflective of Canada’s diversity. For the 2015 federal elections, along with Laidlaw Foundation, Unifor, United Steelworkers Canada , DawaNet and NCCM, Nora led and organized a nationwide election debate for racialized your aimed at improving the strength of democracy in Canada. Nora has spent many years working and advocating for Special Education students. She co-founded the Youth Fellowship, a leadership development program building the next generation of Muslim, Black, Tamil and Filipino public servants. Nora is a change agent who continues to be a strong advocate for students in the public school system in Ontario, facilitating workshops and presentations on topics rooted in Anti-Racism and Anti-Oppression, including presentations at the University of Ottawa and York University.

Shernett Martin

Shernett Martin is the Executive Director of ANCHOR (African Canadian National Coalition against Hate, Oppression and Racism). She has courageously led community campaigns against injustice and racism directed towards School Boards, Municipal government and agencies; bringing together the right people and networks to create significant change and fundamental shifts. She has authored several articles and two online University courses entitled Equity & Inclusion in the classroom and Equity & Diversity Specialist edition. She is the Principal consultant with the Gordon Group and has trained corporations, Government agencies, Police services, unions and School Boards in equity, diversity, anti-oppression and anti-Black racism.

Ms. Martin has been recognized as an exemplary teacher whose teaching style and classroom management skills have been featured in a media campaign for the Toronto District School Board and in various articles in the Voice Magazine. Shernett Martin holds a B.A in Sociology with a focus on Race Relations, Research and Practice, a B.Ed and she is completing a M.Ed from York University. She sits on numerous committees in an advisory capacity and is a mentor to youths throughout the GTA.

Karen Murray

Karen Murray is currently the Centrally Assigned Principal for the Centre of Excellence for Black Student Achievement in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB). She was most recently the Centrally Assigned Principal of Equity, Anti-Racism and Anti-Oppression in the TDSB. Karen leads initiatives focusing on Black Students’ Success and Excellence from K-12 and most recently has been appointed by the Ontario College of Teachers to lead the development of an Additional Qualification on Anti-Black Racism. This is not Karen’s first provincial appointment as she was previously a Student Achievement Officer with the Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat- Ministry of Education. Karen is currently pursuing her PhD at the University of Toronto where her research focuses on Black students’ success. Karen is the co-writer for the Equity Continuum: Action for Critical Transformation in Schools and Classrooms. In 2020, Karen was honoured as one of the 100 Accomplished Black Canadian Women.

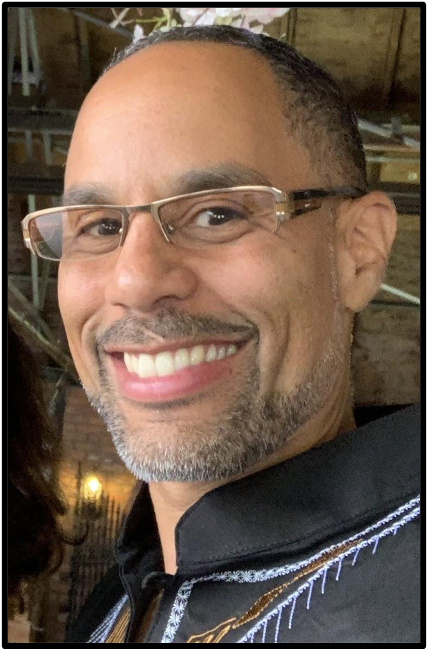

Ramon San Vicente

Ramon San Vicente is currently a principal with the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), educational activist, and author of various texts including Rhymes to Re-Education: A Hip Hop Curriculum. Previously an Instructional Leader with Equitable and Inclusive Schools (TDSB), course director (York University’s Faculty of Education), K-12 Learning Coach (TDSB) and classroom teacher, his work focuses on challenging systems of oppression in education and exploring new possibilities for equitable schooling. Since his MEd thesis on “Black Males, Hip Hop Culture and Public Schooling”, Ramon’s writing and practice have been grounded in critical pedagogies including Critical Race Theory. He is passionate about continuing to learn/unlearn, creating spaces for youth culture in public education and collaborating with others who disrupt oppressive practices in schools. Follow him on Twitter at @RamonSanVicent2.

Alice Te

Alice Te is currently the coordinator of Equity and Women’s Services at the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. She has been an elementary educator and union activist for 30 years. She has had the fortune and opportunity to work in many spaces of learning and has been engaged in the work of anti-oppressive education, intersectional feminism and equity-related pedagogical approaches throughout her personal and professional life. Alice lives in Toronto with her partner and 2 children.