Leading Through In/Visibility

We are grateful to Harpreet Ghuman for helping us deepen our thinking around what Leading Through In/Visibility entails and making connections between ideas that are important to us.

By: H. Ghuman

How do educational leaders push through the experiences of their own invisibility and honour the current generation of learners who look to them for voice and validation?

For many of the panellists featured on this episode, much comes to mind about the identities that are not acknowledged or reflected by those in power, and those identities that are erased from institutional spaces entirely, one way or another. There is a loss of voices, stories, being-ness, contributions, knowledge and wisdom, essence, brilliance and excellence, humanity, and wholeness.

The importance of each of us showing up as our whole selves cannot be underestimated. I say that despite spending some of my schooling experience trying to hide the very essence of my Sikh identity. I often reflect on my faith-based values and teachings from Sikh scriptures around being a voice/ally for those facing oppression and tyranny. SEVA or selfless service for Sikhs can take on so many forms of support and advocacy for others from offering langar and warm meals through the community kitchen to amplifying silenced voices or physically protecting those in harm’s way. This helps to align the work of anti-oppression and anti-racism because it is very much tied to my own personal and spiritual journey. If you see or hear me advocating for Palestinian students or others who have expressed to me their feelings of being unseen or oppressed, know that this is the function of my Sikh identity coming to the surface and the presence of my authentic self in that space. Inherent in these examples is our connected struggles for human liberation - a racial solidarity amongst many tribes and peoples to honour our voices and make our stories visible.

“The greatest teacher will send you back to yourself.” - Nayyirah Waheed

While I am grateful for the strong connection I feel to my Sikh roots and history as an adult, this was not at all the case while I was a student. For about 5 years, Harpreet was known as Mike. In 2020, I wrote a piece entitled, When You See Me that helped me come to terms with some of these schooling experiences. In this piece, I write:

“Cut off my hair, I changed my name, I felt so lost and so ashamed, till I found Malcolm, and found myself, he was the missing book not on the bookshelf.” (Ghuman, 2020, 1:03)

I guess you could say culturally relevant and responsive teaching is not what I was exposed to, and I can imagine the same is true for many of you. How does one feel affirmed when you don’t see yourself or your people’s rich history and contributions? How did this iconic Black leader and figure, Malcolm X, become a doorway for a young Brown boy to discover his Sikh heritage? From 1993 to present day, many words and teachings of Malcolm X and the journey for Black liberation would echo in the mind. Through his words, he became that culturally affirming teacher in some ways, whose words and lessons would guide me back to my own Sikh roots and history. As he shared in one of his landmark speeches:

“Who are you? You don’t know?...And where were you? And what did you have? What was yours? What language did you speak then? What was your name?...And why don’t you now know what your name was then? Where did it go? Where did you lose it? Who took it? And how did he take it? What tongue did you speak? How did the man take your tongue? Where’s your history? How did the man wipe out your history?”

There is no shortage of communities who may be feeling invisible. By naming some of these communities, I know that I will inevitably render invisible those that are not named. From my own work experiences and conversations with students, staff, and families, Tamil, Palestinian, Latin X, East Asian, South Asian, and 2SLGBTQ+ communities have shared their experiences of invisibility through lack of representation and acknowledgment, alongside families from Somalia, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Syria, Vietnam, El Salvador, and Ethiopia. Working with newcomer communities in the Greater Toronto area, whether in Jane and Finch, Crescent Town, Rexdale or Scarborough, I have also learned about the experiences of those who may have entered the schooling system as refugees or as undocumented people as a result of fleeing war, conflict, or other oppressive realities in their countries of birth.

What creates feelings of loss and invisibility? What leads to notions of not being seen or heard? Of course, this differs for all of us, but we might turn our attention to who is left out of books, lessons, conversations, announcements, assemblies, school and community events, teaching placements, and decision-making spaces. We might consider whose histories, identities, causes, and concerns have greater influence and take up more space, because they are actually seen and acknowledged. Even as we work towards anti-racism and anti-oppression, we must continue to ask ourselves which communities continue to fight for the basic recognition of being human.

We might look closely at who is seen and invited to be a leader, and which leaders are considered deserving of recognition and emulation. Which of our familial, cultural, and community experiences are seen as valuable for leadership as assessed through hiring and promotion practices and honoured in professional learning opportunities? We might also notice how students and staff are expected to conform to particular expressions of leadership that are rooted in the worldviews, needs and interests of white, cisgender, able-bodied, Christian, straight, men in a higher socio-economic bracket (Abawi, 2021; Shah, 2022; Turner, 2020). This is precisely where our social location, power and privilege, in systems and in communities, greatly impacts how we move and the risks or rewards we face (Lowery, 2022; Ryan, 2016). Our social locations and positionalities also influence how we strategize, how we mobilize, how we resist, how we build networks, how we develop relationships with community, the knowledge systems we value, and how we imagine different possibilities for education.

In making visible the students, educators, communities, and leaders who have long been invisiblized, we might ask ourselves some of the following important questions:

- How do leaders reconcile past and present-day erasure of particular communities and continue leading as their authentic selves in ways that enable greater visibility for others?

- What enables or inspires us to be more of our full selves and what prohibits us from doing so?

- Do we enter these spaces with a sense of full authenticity, our full sense of humanity and our vulnerabilities or with a somewhat self-censored sense of being?

- How does the over-visibility of some communities and experiences render other communities and experiences invisible? How does power operate in whose stories and experiences are honoured and whose stories and experiences are hidden and denied?

My hope is for each of us to walk into spaces with the pride and strength of our ancestors and communities in ways that outshine the systemic conditioning and silencing.

While I take great pride in serving as a role model to students, families and staff who may identify as Brown, Sikh, Punjabi and South Asian through my role as Superintendent of Education, I recognize how unusual it is for students with these identities to see someone who looks like them in this role. There is no doubt that much work needs to be done in all sectors so that those in power are more reflective of the communities they serve. However, representation through positional power alone will not fully validate those who feel unseen and unheard. In fact, racialized leaders can further enable or perpetuate ideologies of white supremacy, settler colonialism, and other oppressive practices and structures if their practices and work are not grounded in anti-racist and anti-oppressive leadership and grassroots community engagement (Shah et al., 2022). While it is validating for those we serve to see themselves reflected in positions of power, racialized leaders with positional power can also further harm if we do not use this power to support others to see themselves as worthy, dignified, capable, and sacred people. As I noted in a composition entitled 2020, “You could be racialized, don’t make you lesser, brothers doing work, for the oppressor” (Ghuman, 2020). We must amplify the voices of identities currently on the margins in our classrooms and in the broader society, and we must also model taking action both structurally and in our individual leadership practices. This entails serving actively in community and walking alongside marginalized communities (Ghuman, 2009; Ishimaru, 2020). It also entails demonstrating the courage and the will to centre such voices, particularly in institutional and structural spaces. How do we amplify those voices who do not have a seat at the table or who have consistently been blocked from having a seat at the table?

“And now I’m found, and we reclaim, more than identity, more than a name” (Ghuman, 2020, 1:24).

To recognize the histories and contexts of how we became raced and erased, and how we continue to serve a racist system is to resist white supremacy (Shah, 2022). To honor our families, our students, and our communities is to explore the fullness and plurality of our identities, our histories, our experiences, and our futures (Ghuman, 2020). By truly centering the lived experiences of those we serve, we honour their stories and their voices.

And to students everywhere, may you see yourselves, always.

Reflection Questions:

- What experiences, realities and forms of oppression are not visible/not included in more mainstream understandings of oppression?

- How does the racialization of these identities make them simultaneously hyper-visible (difference, accent, political, etc.) and invisible?

- Which identities and experiences are actively ignored? How does the active denial of experiences and identities serve to maintain white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, and other systems of oppression?

- How do we lead through invisibility? Who do we need to be as leaders to challenge this in/visibility?

- How might we apply this understanding to the work we do in communities, schools, and academies?

References:

Abawi Z. (2021). Race(ing) to the top: Interrogating the underrepresentation of BIPOC education leaders in Ontario public schools. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies, 2(1), 80-92. http://johepal.com/article-1-94-en.html

Ghuman, H. (2009). Leading and learning with the community. ETFO Voice. https://etfovoice.ca/feature/leading-and-learning-community

Ghuman, H. (2020). Student Voice. The Register, 23(1) 28-32. https://issuu.com/ontarioprincipalscouncil/docs/opc_fall20-aoda-final

Ghuman, H. [Ghuman H20]. (2020, May 25). When you see me [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2H-4FyCeNY

Ghuman, H. [Ghuman H20]. (2020, December 31). 2020 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cavV4ZZi5O4

Ishimaru, A. M. (2020). Just Schools: Building equitable collaborations with families and communities (J.A. Banks, Ed.). Teachers College Press.

Lowery, K. (2022). ‘What are you willing to do?’: The development of courage in social justice leaders. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(1), 1-20.

Ryan, J. (2016). Strategic activism, educational leadership and social justice. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 19(1), 87-100.

Shah, V. (2022). In/Visible POC: Narratives of a brown professor in teacher education. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 22(2), 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086211051787

Shah, V., Aoudeh, N., Cuglievan-Mindreau, G., & Flessa, J. (2022). Subverting whiteness and amplifying anti-racisms: Mid-level district leadership for racial justice. Journal of School Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1177/10526846221095752

Turner. (2020). Suddenly diverse: How school districts manage race and inequality. University of Chicago Press.

Additional Recommended Resources

Anderson, G. L. (1990). Toward a critical constructivist approach to school administration: Invisibility, legitimation, and the study of non-events. Educational Administration Quarterly, 26(1), 38-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X90026001003

Asian Canadian Educator Network: https://www.acenetedu.ca/

Canadian Tamil Youth Alliance: https://www.facebook.com/CanTamilYouth/

Canadian Tamil Youth Development Centre: https://www.facebook.com/LikeCanTYD/

Hadi, A. S. (2020). Take care of your self: The art and cultures of care and liberation. Common Notions.

Live Well, Take Action: https://www.livewelltakeaction.com/

Mena, & Vaccaro, A. (2017). “I’ve struggled, I’ve battled”: Invisibility microaggressions experienced by women of color at a predominantly white institution. Journal About Women in Higher Education, 10(3), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407882.2017.1347047

Neimann, Y. F. (2012). The making of a token: A case study of stereotype threat, stigma, racism, and tokenism in academia. In G. Gutiérrez Y Muhs, Y. F. Neimann, C. G. Gonzalez, & A.P. Harris (Eds.), Presumed incompetent: The intersections of race and class for women in academia (pp. 336-355). Utah State University Press.

Netolicky, D. M. (2018). The visible-invisible school leader: Redefining heroism and offering alternate metaphors for educational leadership. In O. Efthimiou, S. T. Allison, & Z. E. Franco (Eds.), Heroism and Wellbeing in the 21st Century: Applied and emerging perspectives (pp. 133-148). Routledge.

Osler, A. (2006). Changing leadership in contexts of diversity: Visibility, invisibility and democratic ideals. Policy Futures in Education, 4(2), 128–144. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2006.4.2.128

Shanmugaraj, S. (2023). From Ananthi to Anna: Teacher colonization of student names among Tamil Canadians. Journal of Critical Race Inquiry, 10(1), 43-66. https://jcri.ca/index.php/CRI/article/view/15675

Thatchenkery, T., & Sugiyama, K. (2011). Making the invisible visible: Understanding leadership contributions of Asian minorities in the workplace. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230339347

Waheed, N. (2013). Salt. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Panelists

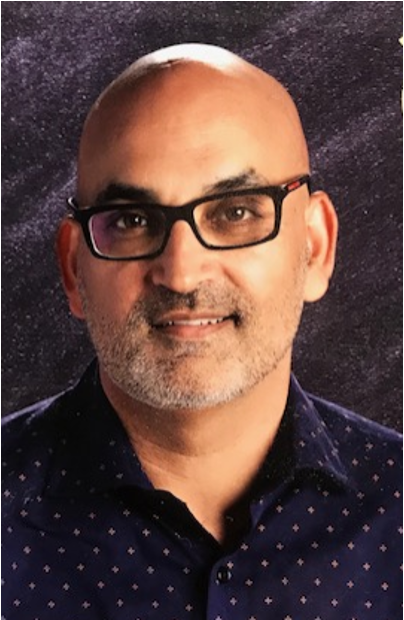

Harpreet Ghuman

Harpreet Ghuman is an educator in the Toronto District School Board with a strong belief in racial solidarity for social change, particularly through Student Voice and Community partnerships. He believes that education plays a critical role in centering the Human Rights of oppressed groups and those not represented in positions of power. This is influenced greatly by the teachings of his Sikh faith and inspired from Black liberation leaders such as Malcolm X. These teachings helped him reconnect with various aspects of his identity that he spent some of his early schooling experiences hiding.

Harpreet enjoys integrating Hip Hop Music through his work with students as a form of storytelling and a platform to affirm their own unique identities. Away from work, he spends a great deal of time journaling as a form of self care and in works of writings that at times have led to musical compositions.

While he’s currently serving as a Superintendent of Education in the TDSB, he prefers to be known as “just a kid from Jane and Finch”. This is done to shed light on a community he feels great pride in having grown up in and to shift dominant narratives of neighbourhoods in the GTA and abroad.

His greatest joy in life is being a father to his sons Kabir and Azaad.

Gen-Ling Chang

Gen-Ling Chang is the former associate director of Toronto District School Board. Currently she is deputy executive director with ALPHA Education. Gen-Ling also serves as chair of school and community with the Asian Canadian Educators Network.

Histories of colonialism and its contemporary versions inform her work on identity, voice, representation, and criticality to question and address power and privilege that create and maintain discrimination and racism. Gen Ling works with youth, educators, and communities.

Cristina Guerrero

Cristina Guerrero is an educator committed to youth empowerment, anti-oppressive practices, and authentic collaboration towards meaningful change in education. She began her career as a secondary school teacher at the TDSB, and later served in positions as an Instructional Leader for the Equity and Inclusive Schools department and as a K-12 Learning Coach.

She holds a Ph.D. in Curriculum Studies and Teacher Development from OISE/University of Toronto. Her doctoral dissertation explored the roles of self-identification, community engagement, and transformative learning among Latinx students involved with “Proyecto Latino,” a joint OISE/University of Toronto and TDSB study utilizing exploratory as well as participatory action research approaches.

Cristina currently works as a Professor in the Bachelor of Child and Youth Care program at Humber College, Lakeshore Campus. She is a Principal Co-Investigator of a 3-year NSERC-funded study entitled “Experiences of hope, self-compassion and authentic collaboration: Foundations for a consumer-informed compassion-based human services delivery framework in a Canadian context”.

Cristina is also an avid runner. She really enjoys running anywhere, whether at home in Toronto or wherever she travels.

Rizwana Kaderdina

Rizwana Kaderdina taught in the elementary panel of the YRDSB for many years before moving into the Board’s Inclusive School and Community Services department as an Equity Consultant. Rizwana is currently the co-Chair of the Alliance of Educators for Muslim Students (AEMS), and is a member of MENO (Muslim Educators Network of Ontario), ACENet (Asian Canadian Educators Network), and al-Ansar Foundation. She also volunteers with Harmony Movement and Victim Services of York Region, Rizwana believes in service, advocacy, and community. Rizwana strives to work from a justice-oriented stance. She is exploring the possibilities for healing and transformation that come through affinity and solidarity-based work.

Muna Saleh

Dr. Muna Saleh is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at Concordia University of Edmonton (CUE), former elementary and secondary school teacher, mother to three wonderful humans, and the author of “Stories We Live and Grow By: (Re)Telling Our Experiences as Muslim Mothers and Daughters.” Drawing upon her experiences as an intergenerational survivor of violent Palestinian displacement and as a caregiver to a child with a dis/ability, her most recent research is a narrative inquiry alongside Muslim mothers of children with dis/abilities who arrived in Canada with refugee experiences.