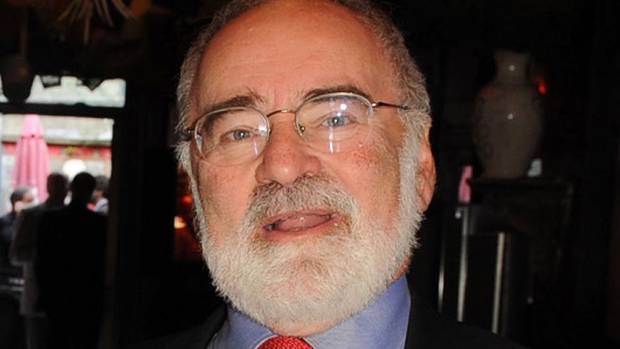

Irving Abella

Special to The Globe and Mail

Irving Abella, Shiff Professor of Canadian Jewish History at York University

(Tom Sandler for The Globe and Mail)

In the 1930s, at the beginning of the Nazi persecution of the Jews, an influential Jewish leader wrote that the world was divided into two parts – “those places where Jews could not live, and those they could not enter.” Canada fell into the latter category. To the condemned Jews of Auschwitz, Canada had a unique meaning. It was the name given to the camp barracks where the gold, jewellery and clothing taken from inmates were stored. It represented life, luxury and salvation. It was also isolated and unreachable, as was Canada in the 1930s and 40s.

Why Canada had arguably the worst record of any Western country in trying to save the doomed Jews of Europe is the subject of None Is Too Many, a book written 30 years ago by Harold Troper and me, and just reissued by the University of Toronto Press.

It is a story that shocked many Canadians who believed the myth that theirs was a country of immigrants with a long history of welcoming refugees and dissidents, a country that has always been in the forefront in accepting the world’s dispossessed and oppressed and where racism and bigotry are foreign creations that play little role in Canadian history or the Canadian psyche.

It is a story of the old, scarcely recognizable Canada of the first half of the 20th century, a benighted, closed, xenophobic society in which minorities were barred from almost every sector of Canadian life. It was a Canada with immigration policies that were racist and exclusionary, a country blanketed by an oppressive anti-Semitism in which Jews were the pariahs of Canadian society, demeaned, despised and discriminated against. Worst of all, this had permeated the upper levels of the Canadian government, the decisions of which closed the country’s doors to the desperate Jews of Europe.

Today’s Canada is far different – generous, open, decent, humane. Multiculturalism is now an integral part of Canadian policy and diversity is encouraged. Yet at a moment when intolerance seems to be the global growth industry of the new century, the lessons of None Is Too Many should not be ignored. Immigration and refugee policies still divide Canadians. There remain significant pockets of discrimination and racism. Nazi war criminals and collaborators, thousands of whom were welcomed into this country immediately after the war, still live freely among us. Clearly, we still have much left to learn from our checkered past.

To our surprise, since its publication, None Is Too Many has taken on a life of its own. We thought it would never be more than a disturbing piece of history describing a shameful period of the Canadian past. Instead, it has become an ethical yardstick against which contemporaneous government policies are gauged. We take pride that our book is often cited in debates over refugee and immigration policy and is often credited with helping make these policies more humane.

We know, for example, that None Is Too Many was instrumental in opening up Canada’s gates to vast numbers of desperate Vietnamese forced out into the rough, pirate-infested waters of the South China Sea in the late 1970s. The Canadian minister of immigration at the time, Ron Atkey, later told us that in the midst of the crisis, while he was being pressured by some to allow the refugees in and by many others to keep them out, he received an advance copy of some chapters of the book. These, he said, emboldened him not to behave in the same callous way a previous government had rebuffed European Jews. His courageous decision opened up Canada’s doors to tens of thousands of valuable new citizens.

And 30 years later, that is our hope – that never again at any time for anyone, should none be too many.

Irving Abella is the Shiff Professor of Canadian Jewish History at York University. A parliamentary celebration marking the 30th anniversary of the book is being held Tuesday evening in Ottawa.