York research: AI better than human eye at predicting brain metastasis outcomes

Lassonde engineers create novel technique they hope will provide cancer patients and clinicians with better, faster information

A recent study by York University researchers suggests an innovative artificial intelligence (AI) technique they developed is considerably more effective than the human eye when it comes to predicting therapy outcomes in patients with brain metastases. The team hopes the new research and technology could eventually lead to more tailored treatment plans and better health outcomes for cancer patients.

“This is a sophisticated and comprehensive analysis of MRIs to find features and patterns that are not usually captured by the human eye,” says York Research Chair Ali Sadeghi-Naini, associate professor of biomedical engineering and computer science in the Lassonde School of Engineering, and lead on the study.

“We hope our technique, which is a novel AI-based predictive method of detecting radiotherapy failure in brain metastasis, will be able to help oncologists and patients make better informed decisions and adjust treatment in a situation where time is of the essence.”

Previous studies have shown that using standard practices, such as MRI imaging – assessing the size, location — and number of brain metastases — well as the primary cancer type and condition of the patient, oncologists are able to predict treatment failure (defined as continued growth of the tumour) about 65 per cent of the time. The researchers created and tested several AI models and their best one had an 83 per cent accuracy.

Brain metastases are a type of cancerous tumour that develops when primary cancers in the lungs, breasts, colon or other parts of the body are spread to the brain via the bloodstream or lymphatic system. While there are various treatment options, stereotactic radiotherapy is one of the more common, with treatment consisting of concentrated doses of radiation targeted at the area with the tumour.

“Not all of the tumours respond to radiation — up to 30 per cent of these patients have continued growth of their tumour, even after treatment,” Sadeghi-Naini says. “This is often not discovered until months after treatment via follow-up MRI.”

This delay is time patients with brain metastases cannot afford, as it is a particularly debilitating condition with most people succumbing to the disease between three months to five years after diagnosis. “It’s very important to predict therapy response even before that therapy begins,” Sadeghi-Naini continues.

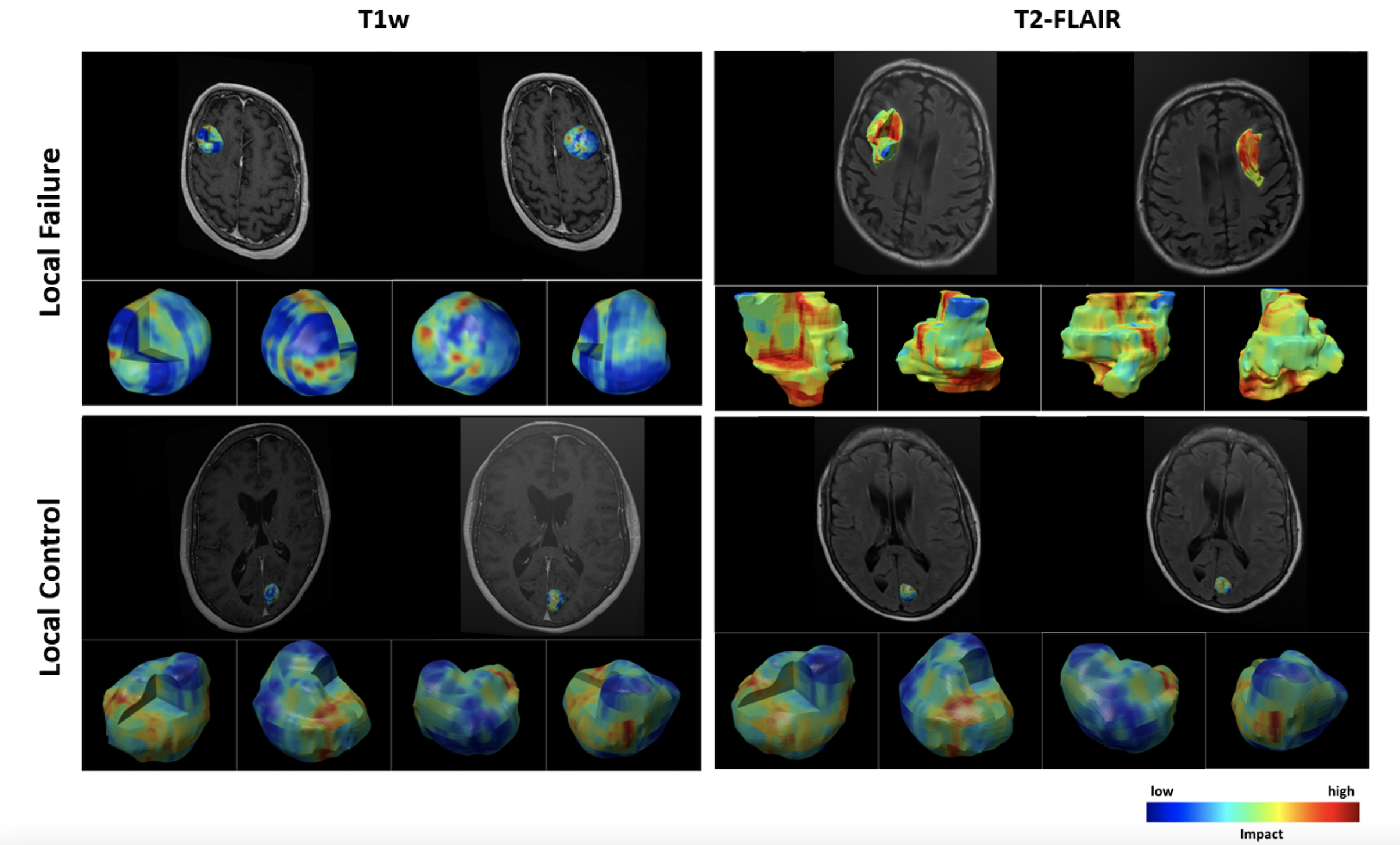

Using a machine-learning technique known as deep learning, the researchers created artificial neural networks trained on a large pool of data, then taught the AI to pay more attention to specific areas.

“When you look at an MRI, you see areas within or surrounding the tumour where the intensity and pattern is different, so you attend to those parts with your vision system more,” explains Sadeghi-Naini. “But an AI algorithm is blind to this. The attention mechanism we incorporated into the algorithm helps these AI tools to learn which part of these images are more important and put more weight on that for analysis and prediction.”

The study, now available online, has been published in the IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine. Partially funded by the Terry Fox Research Institute (TFRI), the modelling work was done at Sadeghi-Naini’s lab at York’s Keele Campus with York PhD student Ali Jalalifar, first author on the study. When it came to data acquisition and interpreting the results from more than 120 patients, the team was able to leverage York’s long-standing collaborative relationship with Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. Other funders of the study included the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Hatch Memorial Foundation.

Sadeghi-Naini says that while more research needs to be done, the findings point to AI being a potentially significant tool in precision management of brain metastasis and even other types of cancer down the line.

The next step to adopting this as a clinical practice would be looking at a larger cohort with a multi-institutional data set, from there a clinical trial could be developed. “If standard treatments can be tailored for patients based on their response to treatments – that can be predicted before treatment even starts – there's a good chance that the overall survival of the patients can be improved,” he concludes.

As part of its long‐standing program involving the best cancer researchers across Canada, the Terry Fox New Frontiers Program Project Grants, TFRI is funding further research in ultrasound and MRI for cancer therapy by Sadeghi-Naini and a team of clinicians and scientists based out of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre to the tune of $6 million over the next six years. Sadeghi-Naini is leading the biomedical computational-AI core of the program, receiving $900,000 of that funding.

-30-

York University is a modern, multi-campus, urban university located in Toronto, Ontario. Backed by a diverse group of students, faculty, staff, alumni and partners, we bring a uniquely global perspective to help solve societal challenges, drive positive change, and prepare our students for success. York's fully bilingual Glendon Campus is home to Southern Ontario's Centre of Excellence for French Language and Bilingual Postsecondary Education. York’s campuses in Costa Rica and India offer students exceptional transnational learning opportunities and innovative programs. Together, we can make things right for our communities, our planet, and our future.

Media Contact:

Emina Gamulin, York University Media Relations, 437-217-6362, egamulin@yorku.ca