To tackle TB, stigma needs to be erased, language transformed, researchers say

Researchers, including those affected by tuberculosis, say a holistic approach is needed to eradicate illness that still kills more than 1.4 million people a year globally and disproportionately affects newcomers and Indigenous communities in Canada

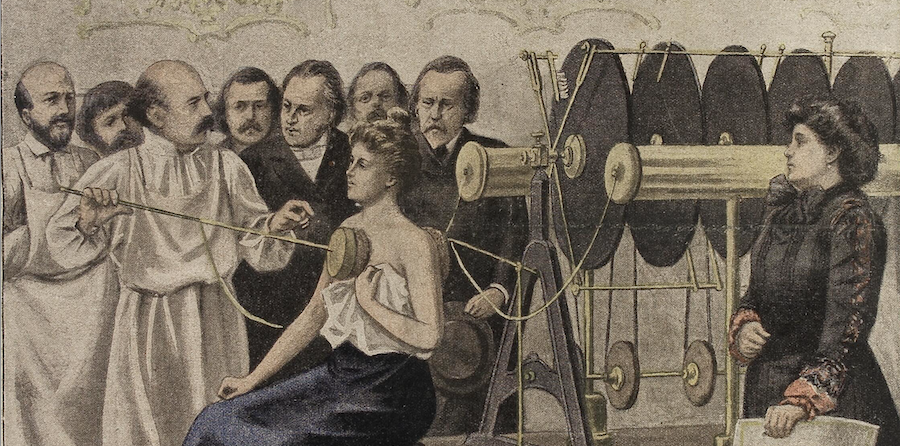

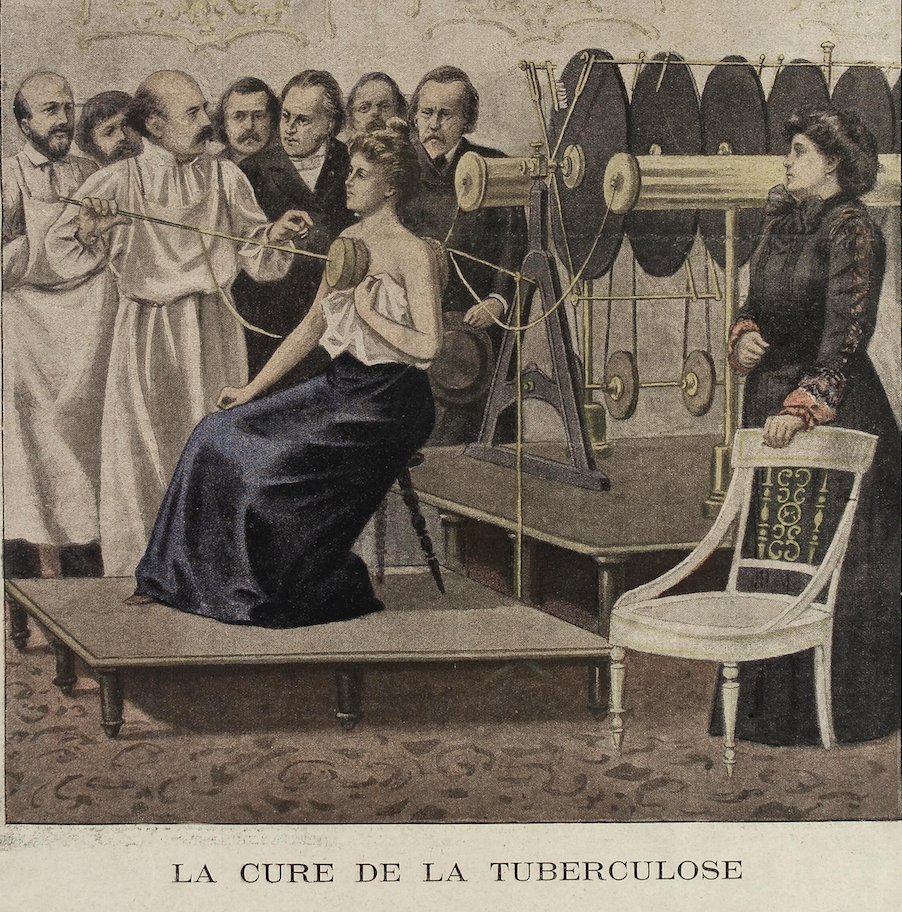

TORONTO, March 23, 2023 – While the bacteria that causes tuberculosis (TB) may be millions of years old and the disease was first recorded in human history thousands of years ago, it remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases globally, with only COVID-19 surpassing it in recent years. TB is also one of the most stigmatized diseases. People are often afraid to visit health facilities, take treatment, or share the news with others.

March 24 is World TB Day, but eradicating TB will require attention beyond one 24-hour cycle. It requires eliminating the social stigma, which includes a shift in how we frame and talk about the illness and those affected by it, say York University and international researchers in a new paper.

“Policing language is not the goal — it's not just about changing the way we talk about TB, but what impact that is going to have on the people and communities that are affected,” says lead author and York University Postdoctoral researcher Beauty Umana, a Global Health Scholar with the Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research at the University and a sociolinguist who studies how language can interact with disease treatment. “Empowering, destigmatizing language in TB would give people affected by it the opportunity to be included, and take ownership of the healing process, and even the care itself.”

The paper was published this afternoon in PLOS Global Public Health under the senior authorship of Amrita Daftary, a TB stigma researcher and founding director of York’s Social Sciences & Health Innovations For TB Centre.

“It's one of those underdog illnesses. It's not received as much attention on a global scale in terms of funding investment, political commitment, or support as some of the other diseases that have affected more affluent countries, different types of populations. But it's entirely preventable, it's curable and treatable,” says Daftary.

Contributor Rhoda Lewa, an independent consultant from Nairobi, Kenya who works on programming and policymaking for HIV, TB and malaria, developed TB in her early 20s while studying at university and knows the stigma of the illness all too well.

“Having to go through the entire treatment regimen without my entire family knowing, without my colleagues knowing, it was not an easy task,” says Lewa. “It takes more than new drugs and new technologies to overcome TB. Language is a very powerful lens. With the power of the tongue, you can either build or destroy, you can encourage or deflate somebody.”

While the researchers say that the language is evolving, a lot of what is used in practice still has negative connotations, including that of criminality. For example, people being referred to as TB “suspects” and “cases,” and those who don’t finish a course of treatment being referred to as “absconders.” Terms such as “vulnerable populations” can also be disempowering.

But, Umana emphasizes, it is not just about individual words, but also how those words are contextualized. For example, treatment management files that are written in a way where the person with TB is seen to be a problem, rather than the illness itself and barriers a person may experience to treatment.

The World Health Organization estimates that in 2021, more than 10 million people were diagnosed with tuberculosis and 1.4 million died, despite antibiotics being available. In Canada, while rates are overall very low, newcomers and Indigenous communities are greatly overrepresented compared with the general Canadian population. In Canada, and all over the world, tuberculosis is often talked about as an illness of poverty, which further stigmatizes those who develop the illness, the researchers say.

The UN has set a Sustainable Development Goal to eradicate TB by 2030.

Umana, Daftary and Lewa, as well as collaborators Jessica Vorstermans, James Malar and Deliana Garcia, hope to change how people talk about the disease, and some of them were also involved in developing a TB language guidance Words Matter.

“Compassionate language is about people who are affected by tuberculosis seeing themselves in those words and saying ‘You know what? This is my story, this is my life, and I’m going to take full control of it,’” says Umana.

Watch a video of Umana and Lewa explain why compassionate language matters.

About York University

York University is a modern, multi-campus, urban university located in Toronto, Ontario. Backed by a diverse group of students, faculty, staff, alumni and partners, we bring a uniquely global perspective to help solve societal challenges, drive positive change, and prepare our students for success. York’s fully bilingual Glendon Campus is home to Southern Ontario’s Centre of Excellence for French Language and Bilingual Postsecondary Education. York’s campuses in Costa Rica and India offer students exceptional transnational learning opportunities and innovative programs. Together, we can make things right for our communities, our planet, and our future.

Media Contacts: Emina Gamulin, York University Media Relations and External Communications, 437-217-6362, egamulin@yorku.ca