Becoming Professor Carl James

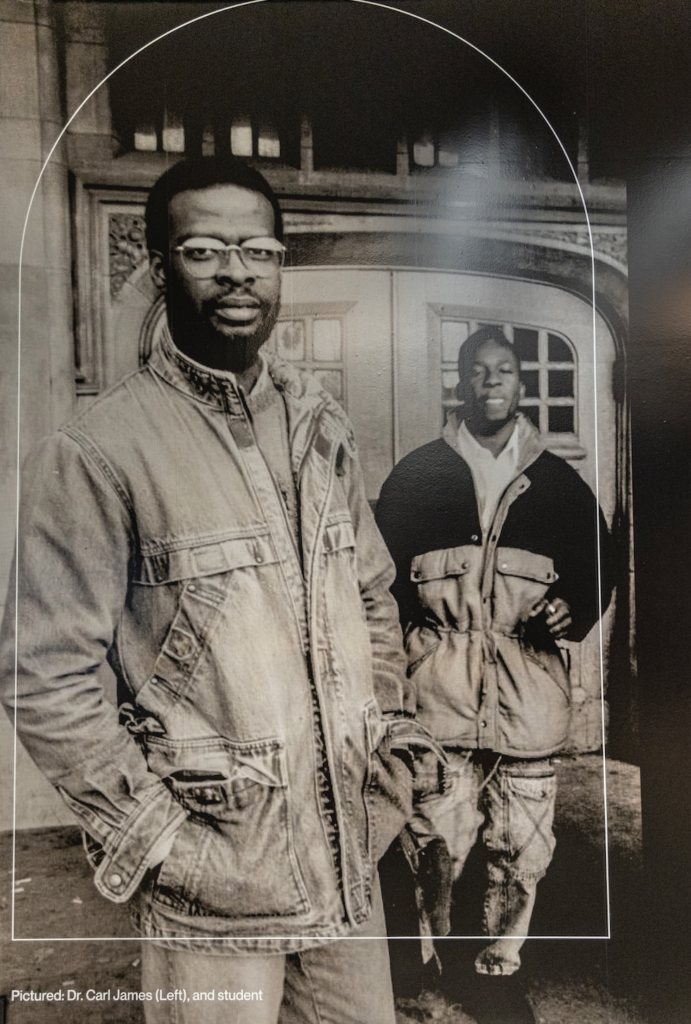

Now a prominent academic, York's Faculty of Education Jean Augustine Chair reflects on experiences of Black community in 1970s Toronto

It was at the now-closed Brockton High School near the new Dufferin Mall on what was then called Awde Street, where a young Carl James met with other community organizers on a September Saturday. That morning they launched the Caribbean Alliance Council (CAC) and that evening they celebrated with dinner and dance at the Soul Palace Restaurant, just north of what is now Sankofa Square.

Like other Black immigrants of his generation from Antigua, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Trinidad and Tobago and other Caribbean islands, James came to Canada in the post-1967 period after the state had removed race-based immigration restrictions.

While pursuing his education, James engaged in youth work, volunteering with organizations such as the Black Education Project. Located just north of Davenport on Bathurst, James describes the organization as “central” to the education experiences of Black parents and students at the time. He also worked with Harriet Tubman Centre at St. Clair and Oakwood, which still operates today as the Harriet Tubman Community Centre close to Don Mills subway.

“I was at the time going through school, volunteering and working with the other volunteers – an adolescent working with younger Black adolescents,” recalls James. “I came to the work that I do through working on issues of Black life. The situation that I was observing and trying to understand with regard to Black youth informed my work.”

Later, he worked in Regent Park, a neighbourhood located in Toronto’s east downtown that’s now a mix of condominiums and social housing. Back then it was exclusively a public housing project – Canada’s first and largest. Many of the youth with whom James worked saw their participation in sports as the key to their future success and were not often going into academic areas because of streaming practices in their schools.

This inspired his early research at York University. Today, James is a prominent academic who has dedicated his career to studying some of the very issues he first observed and experienced four decades earlier.

“I'd been noticing that the education and schooling system had not been as helpful in educating or schooling Black immigrant students as we would have expected,” recalls James. “That happens today; and happened then. So, I'm very interested in, well, ‘How can this change? If over and over again, we keep finding and seeing the same thing, what have we not been doing to change the situation?’”

In addition to being a professor in York University’s Faculty of Education and an author of many books on race, education and immigration, James currently serves as the Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community and Diaspora.

His 2017 report Towards Race Equity in Education highlighted the systemic racism Black students face in GTA schools. This work helped to bring about an end to academic and applied streaming for Grade 9 students in Ontario, a decision that was announced in 2020.

Current projects through the Chairship include community outreach, such as the Day at York programming that helps Black high-school students see themselves in post-secondary, the Jean Augustine Mentorship program that pairs Black students at York with those entering the university, and Word, Sound, Power, a free annual event that takes place during Black History Month with dance, music and spoken word performances. It also includes partnerships with Black researchers across Canada that will serve to create better data on race and education, and collaborations with health science researchers looking at the health conditions and needs of Black individuals.

James is also a frequent figure in the media, commenting on recent news headlines from the renaming of Dundas Square, to new rules banning the N-word from use at several school boards, diversity in the city’s emergency services, and the provincial government mandating Black history in the Ontario curriculum.

However, it is not about him, James insists, nor the research, but working in the interest of community and using advocacy work to address and bring about the wider changes needed.

“It is not about research for research’s sake, but to inform action,” says James. “Community is often a central feature for those who have been marginalized. Of course, I think you can’t think of someone independent of their communities. And I'm thinking of communities not only in geographic terms, but as ethnic communities, gendered communities, class communities, and how all these might be operating in individuals’ lives.”

I'd been noticing that the education and schooling system had not been as helpful in educating or schooling Black immigrant students as we would have expected. That happens today; and happened then."

Professor Carl James, commenting on his early experiences working with youth in Regent Park

James adds that community is often a central construct of how Black youth imagine their future lives.

“You might find them highly represented in social services, social sciences, and education because they are ‘giving back’ to community,” he says. “They feel an obligation to respond to the needs of the community that has supported them. So, it's understandable that Jean would think that community is central to the work that’s been done through the Chair and for the Chair to engage community.

“Essentially, the idea is for us to work with community, and invite them to do the needed education work together.”

One of his current research projects looks at how individuals’ social capital – racialized individuals in particular – mediates access to employment, careers and occupational mobility once they land a job. Like much of James’s other work, the study follows research participants over a number of years, with a particular focus on periods of transition.

“I'm very interested in the differences between transitioning through high school to college and/or university, or from university to college, and to work,” says James. “All those permutations are very useful to look into in order to capture the ways in which young people are navigating life and negotiating the world around them.”

The Chairship is of course named after Jean Augustine, Canada’s first Black woman Member of Parliament, who made the motion that was unanimously passed in the House of Commons in 1995 for Black History Month to be officially recognized in Canada. She later established the Chair in her name at York University. James became the second Chair after the role was restructured and reimagined from the original framing of ‘Education in the New Urban Environment,’ which was held by Professor Nombuso Dlamini. Thanks to a combination of a $1.5 million gift from the federal government and grassroots funding, the Chair is now fully endowed. (Her actual, physical chair, that she once sat in as an MP, now sits in the Dean’s Office at the Faculty of Education).

James’ initial connections with Augustine go back to his early years in Toronto and their mutual involvement in community organizations such as the CAC.

Some documentation of this can be found in the Jean Augustine collection hosted through the Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections at York University’s Scott Library, such as a letter regarding the founding meeting, written and signed off by James on behalf of Augustine, then the secretary of the CAC. At that meeting, James asked the group about working with high school students and recommended a summer research project looking into the experiences of immigrant children from local communities.

James is being celebrated in two pieces of art this Black History Month – one by York alumni Robert Small as part of the Legacy Collection, and the other by Mya Salau as part of this year’s Toronto Transit Commission’s (TTC) Black History Month campaign, Building on Legacies: Celebrating Black Excellence in Toronto. Salau’s piece can be seen on an oversized mural at the York University TTC subway station, a wrap on Bus #3349 that operates on various lines deployed from the Queensway Garage, and on subways across the city.

A lot has transpired in the decades since James began his work, but it was in those early experiences with Black communities in Toronto that set him on his life path.

“I always say, suppose I never worked with those downtown youth. Would I have been able to think of the questions I have today?” he reflects. “Suppose they never answered my questions, or even sat with me for half an hour to share their experiences.

“So, while I look earnestly at the people who have worked with me, and given me mentorship, I have to also remember the research participants or even those who just simply entertained my conversations and my questions to think through more of what I might want to eventually contribute to life.”

James is not the only member of the York community to be celebrated by the TTC as part of Black History Month. Honorary Doctor of Laws degree recipient Itah Sadu, is also featured in a mural at Bathurst station. Watch Sadu, James and other honourees speak to CityTV News about the mural campaign.

Jean Augustine's story teaches us about Canada's domestic workers’ scheme

Augustine had come to Canada as a domestic worker from Grenada during a time of political upheaval in her home country, with Grenada achieving independence in 1974. These early days are documented in the Jean Augustine collection hosted through the Clara Thomas Archives at York University’s Scott Library located at Keele Campus.

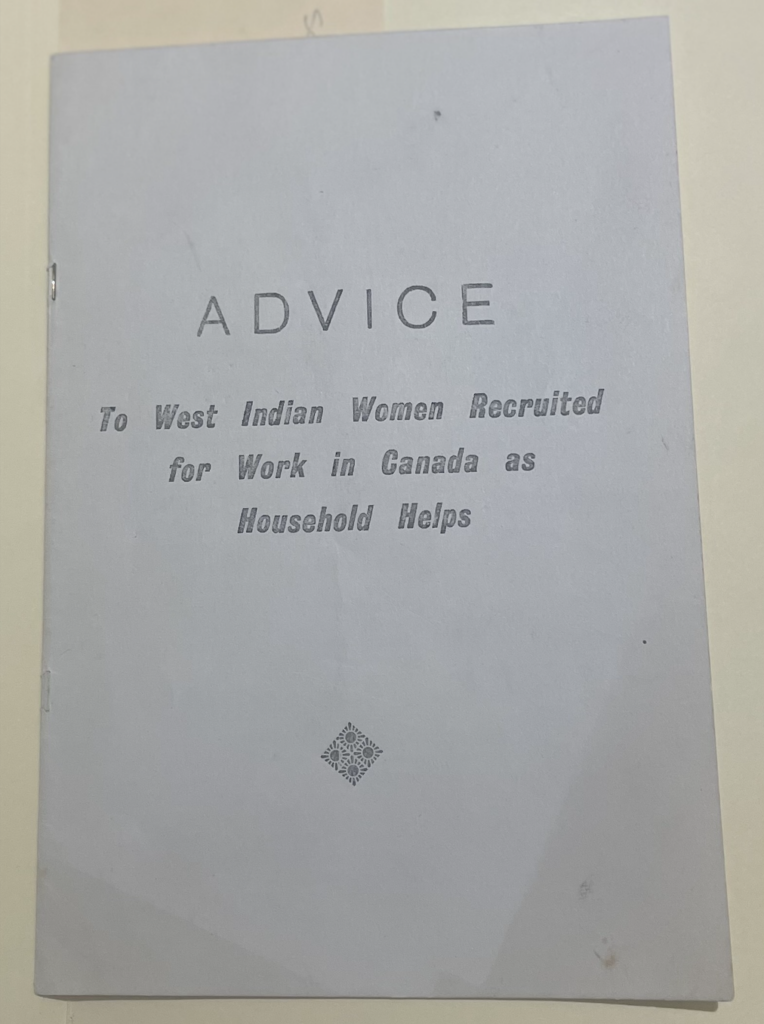

The first item in the archive is a pamphlet entitled Advice to West Indian Women Recruited for Work in Canada as Household Helps. A lot of the space in the pamphlet is devoted to advice on what behaviour is expected: Be truthful, courteous and polite at all times in your dealings with your employer and their children; unmarried women who get pregnant in their first year could be deported and may never be able to return.

“The women who have been sent to Canada in previous years have not let down West Indian womanhood and it is confidently expected that you will do the same,” a passage reads.

The pamphlet also contains practical advice on life in Canada: While it is easy to get credit, it is also easy to get in trouble with it if you can’t keep up with payments; bring warm clothes, but no more than is needed as it will be cheaper to purchase winter clothes after you arrive; if your lips get chapped, try Vaseline or Camphor Ice.

There are warnings of “useless correspondence courses,” especially in nursing, that will take large sums of money, but won’t be of any use either in Canada or back home.

Canada needed more immigrants in the post WWII period when Europeans were staying home, and it was in that context that the Canadian government allowed workers from certain territories in the West Indies entry to Canada beginning in 1955, and the total lifting of race-based immigration restrictions in 1967. Caribbean domestics came to Canada to take care of other people’s children so those people could go to work, explains James. And people like Augustine who were teachers back home, not only provided domestic duties, but also the socialization of Canadian children.

“Beyond simply thinking of Jean coming here and becoming a Parliamentarian, what does Jean's story also tell us about Canada? To me, it's a big or national story,” reflects James.

“Her story represents Canada’s relationship with the Caribbean, and Caribbean women’s, and people’s contributions to the social, cultural, economic and political development of Canada. Her story is important; and there are many things we can learn from it.”

Members of the York University community and public can access the Jean Augustine collection by appointment by contacting the Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections at archives@yorku.ca.