Moving forward while learning from past vital, York U Black History Month panellists

“February is Black History Month, but we make history every day” –

Ruth Rodney, associate director, Harriet Tubman Institute

Education, particularly math education, is not a neutral space for Black students. It continues to be a space where there are fewer expectations of success. That was one of the messages that emerged during the Black History Month panel on education, Black Educators and Black Education, at the Harriet Tubman Institute at York University.

As Assistant Professor Molade Osibodu of York’s Faculty of Education told the audience – inequities persist for Black learners.

“There is a lot of overt racism at play in education that we have to pay attention to, but there remains a lot of push back. The system of mathematics needs to change so that young people, especially young Black people, feel like they don't belong in this space,” says Osibodu, who was one of five panellists.

The panellists were from a range of disciplines and included Assistant Professor Godfred Boateng in York’s School of Global Health; Professor Lawrence Goodridge, director of the Canadian Research Institute for Food Safety at the University of Guelph; Assistant Professor Ola Mohammed of York’s Department of Humanities, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional Studies; and Associate Professor Solomon Boakye-Yiadom of the Lassonde School of Engineering (who will be in Ghana in March to do a STEM workshop with high school students) also participated.

One of the main messages was that structural change is needed to address the architecture that skews the playing field. While ending math streaming for Grade 9 students, particularly Black students, into the applied or academic level at high school is great, “Black students need to feel welcome, they need to feel they belong in these educational spaces,” says Osibodu.

Panellists also discussed how colonizers took credit for indigenous knowledge across their colonies. When the French and English first landed on the West Coast of Africa, Indigenous Black people taught them how to treat tropical diseases. In places such as South America, the colonists learned of an indigenous malaria cure – quinine – using the bark of the Cinchona tree, says Boateng. The colonizers later used that knowledge to create synthetic anti-malarials such as Chloroquine, which was then sold back to people in these colonies.

“Some of the things that were learned were not ascribed to the indigenous [populace]. It became sort of the property or the proprietary of those who came to the land. It was stolen, plagiarized.”

A more recent example was the discovery of the Ebola virus, which should have been attributed to a Congolese doctor Jean-Jacques Muyembe, but was instead largely credited to Dr. Peter Piot of Belgium at the time, says Goodridge.

Biases also play a huge role in which diseases get funding to create vaccines. Boateng also takes issue with the huge influx of resources to create a vaccine for COVID-19. While he doesn’t begrudge a vaccine being developed for SARS-CoV-2, he does question the scale of worldwide resources dedicated to it when malaria has killed millions, more than 600,000 in 2022 alone, mostly in Africa, with 78 per cent of them children under the age of five, according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) figures. The first malaria vaccine wasn’t recommended for public use by the WHO until 2021.

Many universities now have Black studies programs, including York, but Mohammed says the first Black studies department began at San Francisco State University in 1968, although informally it started years before and the work is also happening in spaces beyond academia. One of the questions Mohammed had is: “How do we organize to create more opportunities, not just for Black education, but for our community to learn and have the language and development to challenge and create change.”

Despite everything, several panellists believe there is hope.

“While the beginnings have not been that great. Today we can speak of black educators making an impact or having an impact in their field,” says Boateng. “I believe that if we are empowered, it becomes easier for us to tell you the story.”

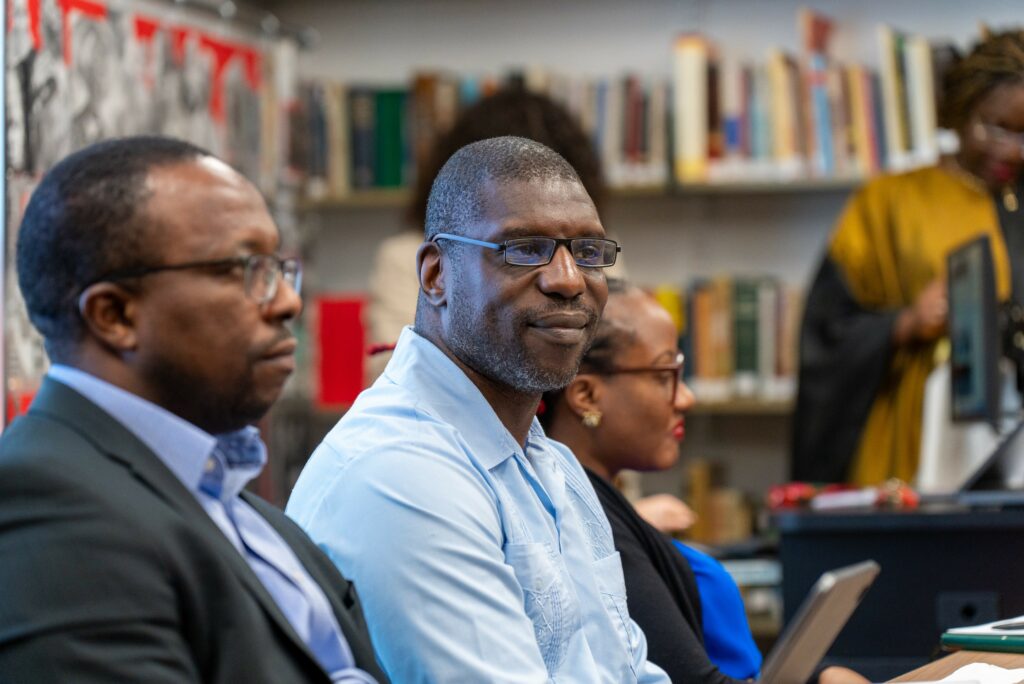

Banner photo by Shayne Phillips