Astronauts have surprising ability to know how far they ‘fly’ in space

York-led findings show astronauts can safely assess distances in weightless environment

TORONTO, March 25 2024 – New research led by York University finds astronauts have a surprising ability to orient themselves and gauge distance travelled while free from the pull of gravity.

The findings of the study, done in collaboration with the Canadian Space Agency and NASA, have implications for crew safety in space and could potentially give clues to how aging affects people’s balance systems here on Earth, says the study’s lead Faculty of Health Professor Laurence Harris.

“It has been repeatedly shown that the perception of gravity influences perceptual skill. The most profound way of looking at the influence of gravity is to take it away, which is why we took our research into space,” says Harris, an expert on vision and the perception of motion who also heads up the Multisensory Integration Lab and is the former director of the Centre for Vision Research at York.

“We’ve had a steady presence for close to a quarter century in space and with space efforts only increasing as we plan to go back to the moon and beyond, answering health-and-safety questions only becomes more important. Based on our findings it seems as though humans are surprisingly able to compensate adequately for the lack of an Earth-normal environment using vision.”

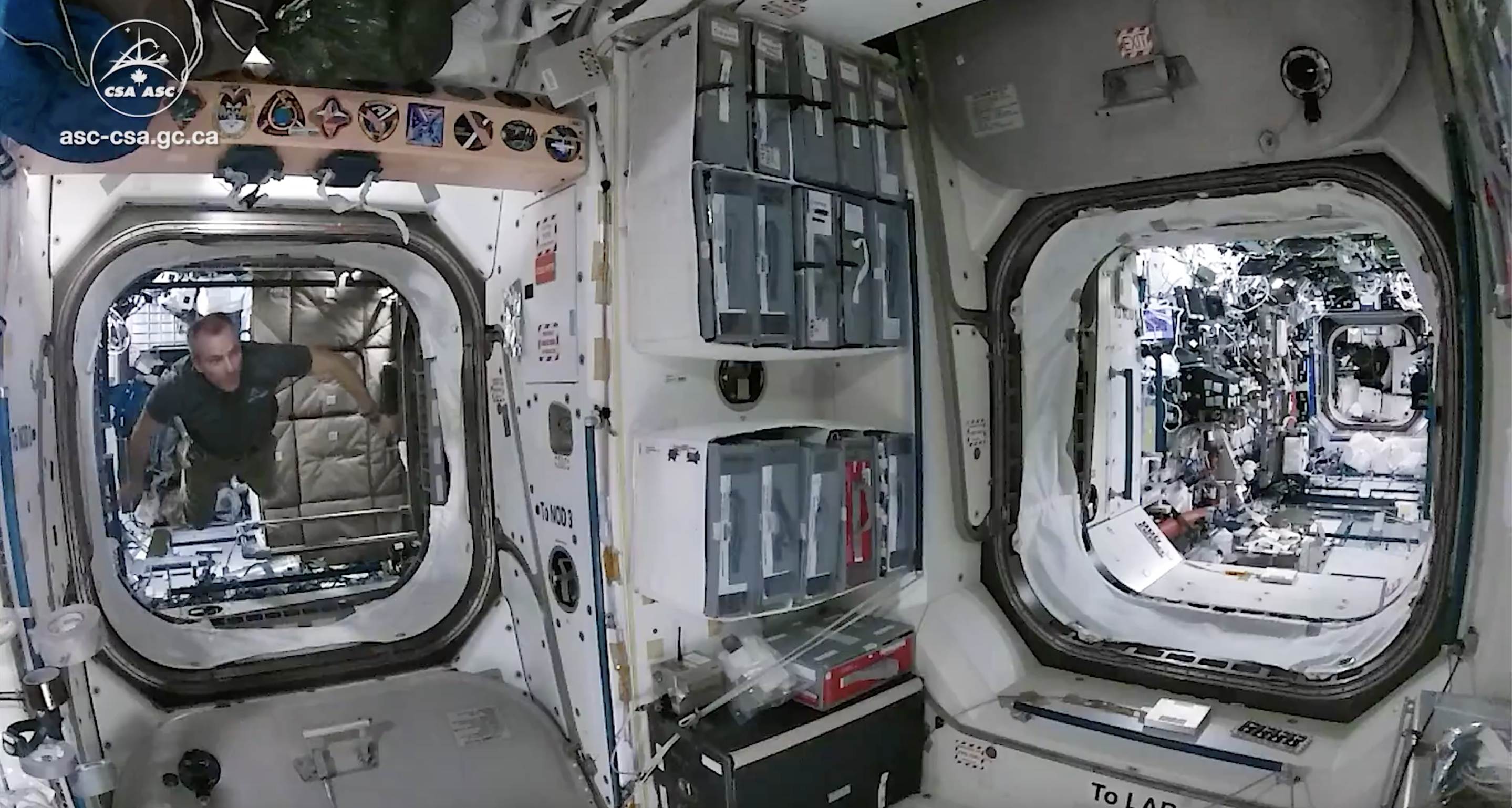

Harris and collaborators – who include Lassonde School of Engineering professors Robert Allison and Michael Jenkin, and two generations of York post docs and graduate students Björn Jörges, Nils Bury, Meaghan McManus and Ambika Bansal – studied a dozen astronauts aboard the International Space Station, which orbits about 400 kilometres from the Earth’s surface. Here, Earth's gravity is approximately cancelled out by centrifugal force generated by the orbiting of the station. In the resulting microgravity, the way people move is more like flying, says Harris.

“People have previously anecdotally reported that they felt they were moving faster or further than they really were in space, so this provided some motivation to actually record this,” he explains.

The researchers compared the performance of a dozen astronauts – six men and six women – before, during, and after their year-long missions to the space station and found that their sense of how far they travelled remained largely intact.

Space missions are busy endeavours and it took the researchers several days to connect with the astronauts once they arrived at the space station. Harris says that it’s possible their research was unable to capture early adaptation that may have occurred in those first few days, “it's still a good news message because it says that whatever adaptation happens, happens very quickly.”

Space missions are not without risk. As the ISS orbits the Earth it is sometimes hit with small objects that could penetrate the vessel requiring astronauts to move to safety.

“On a number of occasions during our experiment, the ISS had to perform evasive maneuvers,” recalls Harris. “Astronauts need to be able to go to safe places or escape hatches on the ISS quickly and efficiently in an emergency. So, it was very reassuring to find that they were actually able to do this quite precisely.”

The study, published recently in npj Microgravity, has been a decade in the making, and represents the first of three papers that will emerge from the research investigating the effects of microgravity exposure on different perceptual skills including the estimation of body tilt, travelled distance, and object size.

Harris says research shows exposure to microgravity mimics the aging process on a largely physiological level – wasting of bones and muscles, changes in hormonal functioning and increased susceptibility to infection – but this paper finds that self-motion is largely unaffected, suggesting the balance issues that frequently come from old age may not be related to the vestibular system.

“It suggests that the mechanism for the perception of movement in older people should be relatively unaffected, and that the issues involved in falling may not be so much in terms of the perception of how far they've moved, but perhaps more to do with how they're able to convert that into a balance reflex.”

About York University

York University is a modern, multi-campus, urban university located in Toronto, Ontario. Backed by a diverse group of students, faculty, staff, alumni and partners, we bring a uniquely global perspective to help solve societal challenges, drive positive change, and prepare our students for success. York’s fully bilingual Glendon Campus is home to Southern Ontario’s Centre of Excellence for French Language and Bilingual Postsecondary Education. York’s campuses in Costa Rica and India offer students exceptional transnational learning opportunities and innovative programs. Together, we can make things right for our communities, our planet, and our future.

Media Contacts: Emina Gamulin, York University Media Relations and External Communications, 437-217-6362, egamulin@yorku.ca