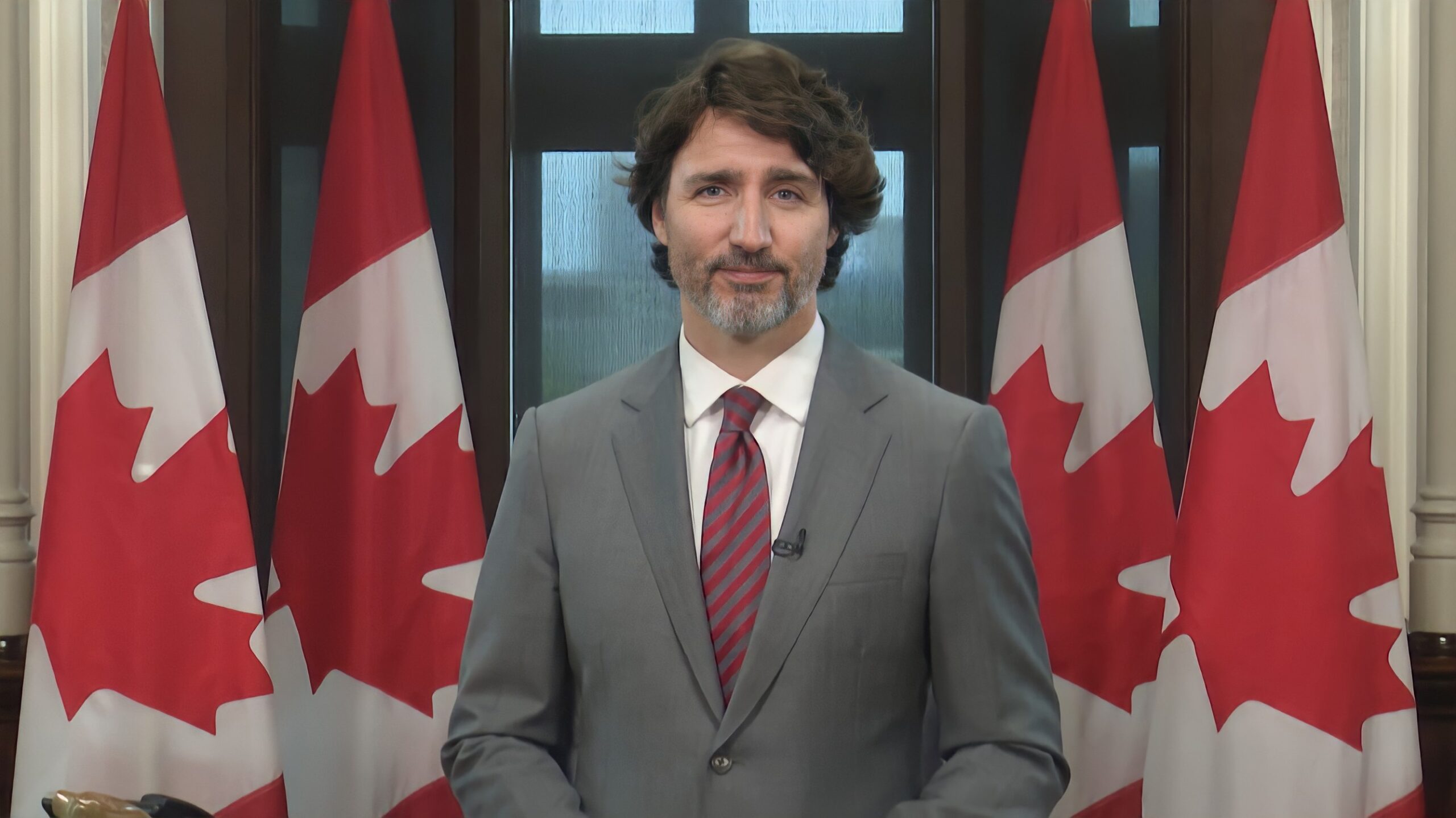

Justin Trudeau is leaving his stamp on the Supreme Court of Canada

With the recent resignation of Supreme Court Justice Russell Brown, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will appoint his sixth Supreme Court judge. That amounts to nearly one new justice for every year Trudeau’s been in power.

Canada’s Supreme Court is not as politicized as that of the United States. Donald Trump’s three appointments during his single term as president dramatically shifted the court’s decisions, especially on abortion rights.

Nonetheless, the people who serve on the highest court in Canada also wield significant influence over the lives of Canadians.

Cases reach the Supreme Court because the laws passed or decisions made by politicians cannot account for every possible eventuality.

Rulings by the Supreme Court can therefore directly impact Canadians in many ways, running the gamut from same-sex rights to Indigenous treaty rights, private health care, the right to medically assisted death and the ability of the federal government to set carbon taxes.

The Supreme Court also provides advice on the constitutionality or interpretation of federal or provincial legislation that dramatically affects the country. An example is the Supreme Court’s opinion in 1981 on patriating Canada’s Constitution and its 1998 guidance involving the right of a province to separate from Canada.

Cementing his legacy

Trudeau has been granted an unexpected opportunity to cement his legacy. Supreme Court justices serve until age 75, when they must retire.

Justice Michelle O’Bonsawin, the most recent Trudeau appointee, could serve until 2049. Mahmud Jamal, appointed by Trudeau in 2021, could serve until 2042. By then, Trudeau will be long gone from the political arena, but his priorities and values will continue to shape the nation.

In fact, the Supreme Court already bears Trudeau’s stamp given O’Bonsawin is the first Indigenous Supreme Court justice and Jamal is the first racialized Canadian to be named to the court.

Brown, from Alberta, filled one of two seats on the court historically allocated to justices from western and northern territories and provinces.

Given the fraught relations between Ottawa and Alberta, Trudeau may be unlikely to nominate an Albertan. He might appoint someone from Saskatchewan, which has not had a representative for half a century.

Selection process begins

Trudeau has opened the process to select the next Supreme Court justice.

Only judges and lawyers from western and northern Canada can apply to the Independent Advisory Board for Supreme Court of Canada Judicial Appointments that will soon provide Trudeau with a list of three to five candidates.

Trudeau is not obliged to select a name from the list, but he’s previously always drawn from it. Unlike earlier prime ministers, Trudeau has already specified that candidates must be functionally bilingual.

There are currently four women and four men on the court. Trudeau could make history by naming a woman, which would create, for the first time, a Supreme Court with more women than men.

The Supreme Court has long been a bastion of male privilege, with the first woman, Bertha Wilson, only appointed in 1982 after intense pressure from feminist groups. The prime minister who facilitated that shattering of the court’s glass ceiling was Justin Trudeau’s father, Pierre.

The Charter’s influence

Many cases that reach the Supreme Court require justices to decide whether to interpret a law in a literal sense or to also ponder the social, political and economic context that gave rise to the legislation. That includes the intentions of the lawmakers.

The enactment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 dramatically increased the role of the Supreme Court. That’s because the Charter outlines the rights and freedoms of Canadians in general terms, but then goes on to note these are not absolute.

These inherent tensions in the Charter gave the court an activist role in public policy. Prior to the 1980s, the Supreme Court had mainly dealt with the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments — specifically, which level of government had been granted responsibility for what in 1867.

After 1982, the Supreme Court often had to determine which laws were consistent with the Charter and to clarify central aspects of the Charter. In doing so, many decisions relied in some measure on the justices deciphering the intent of the politicians who enacted the legislation in question.

In 1995, for instance, the Supreme Court ruled that sexual orientation is constitutionally protected under the equality clause of the Charter, even though there is no mention of sexual orientation in the document. Sexual orientation was ruled to be an “analogous ground” to those listed in the Charter: race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

In the decades to come, Canada’s Supreme Court will undoubtedly issue rulings related to climate change, Indigenous Peoples, individual rights, the impact of technology, international relations and much more.

As with past rulings, these will shape the lives of Canadians in matters large and small. And Trudeau’s foresight will likely be evident in some of those decisions.

By Professor Professor Thomas Klassen, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional Studies, York University.

This article is republished from The Conversation Canada