Reading to improve language skills? Focus on fiction rather than non-fiction

We all know that reading is good for children and for adults, and that we should all be reading more often. One of the most obvious benefits of reading is that it helps improve language skills. A major review of research on leisure reading confirmed that reading does indeed foster better verbal abilities, from preschoolers all the way to university students. But, does it matter what we read?

In four separate studies, based on data from almost 1,000 young adults, behavioural scientist Marina Rain and I examined how reading fiction and non-fiction predicts verbal abilities.

We found that reading fiction was the stronger and more consistent predictor of language skills compared to reading non-fiction. This was true whether people reported their own reading habits or if we used a more objective measure of lifetime reading (recognizing real author names from among false ones). Importantly, after accounting for fiction reading, reading non-fiction did not predict language skills much at all.

Measuring meaningful language skills

To measure verbal abilities in three of these studies, we relied on items from the verbal section of the SAT, the standardized test used by many U.S. universities when judging applicants. Thus, the measure of language skills employed in these studies is rather obviously tied to an important real-world outcome: admission to university.

Although it was somewhat surprising to discover that reading fictional stories predicts valuable language skills better than reading non-fiction, the repeated replication of this result across several studies increased our confidence in this finding.

Motivations behind leisure reading

In a follow-up study, a collaboration between my psychology lab at York University and a lab at Concordia University led by education professor Sandra Martin-Chang, we asked 200 people about their various motivations for engaging in leisure reading.

Those who reported that they read for their own enjoyment tended to have better language skills. Related to our previous finding, this association was partially explained by how much fiction they had read.

In fact, across several types of motivation, those motivations linked to reading fiction rather than non-fiction were invariably associated with better verbal abilities. On the other hand, when a motivation was more strongly associated with reading non-fiction it tended to be either unrelated to verbal abilities or associated with worse abilities.

For example, people who were motivated to read in order to grow and learn focused on reading non-fiction, so this attitude was actually associated with poorer language skills.

Reading stories

Based on these five studies, the picture is quite clear: it is reading stories, not essays, that predicts valuable language skills in young adults. But why does reading fiction have this unique advantage over non-fiction? We don’t yet exactly know, but we can rule out one obvious possibility: that fiction employs SAT words more often than non-fiction.

To investigate this possibility, we turned to several large collections of texts, containing around 680 million words in total. Words that appeared in the SAT were either less common in fiction compared to non-fiction, or the difference was so small it was negligible.

Fiction readers are therefore not doing better on SAT items simply because fiction contains more SAT words. This means that there must be something special about reading fiction that helps promote language skills. Perhaps the emotions evoked by stories help us to remember new words, or maybe our intrinsic interest in stories results in a stronger focus on the text. Future research will hopefully uncover the reasons for this fascinating difference between reading fiction and non-fiction.

Long-term benefits of reading

Regardless of the reasons, the fact that it is narrative fiction and not expository non-fiction that helps us develop strong language skills has important implications for education and policy.

When it comes to reading, it really is a case in which the rich get richer: A great deal of past research has established that those who read more tend to get better at reading, find it easier and more enjoyable and read more as a result. This results in a causal loop in which leisure reading reaps increasingly larger benefits for readers in terms of language skills. Remarkably, this remains true all the way from preschool to university.

These improved language skills in turn result in all kinds of important advantages, such as doing better at school, attaining a higher level of education and being more successful at work.

In fact, one study of over 11,000 people found that children who were better readers at age seven had a greater degree of socio-economic success 35 years later! This held true even after accounting for important factors like their socio-economic status at birth, intelligence and academic motivation. Leisure reading is important for developing language skills, which in turn are linked to key socio-economic outcomes.

Implications for education and policy

Work from our lab, based on young adults, is beginning to clarify the association between reading and language abilities, pointing to the importance of reading fiction and not just non-fiction.

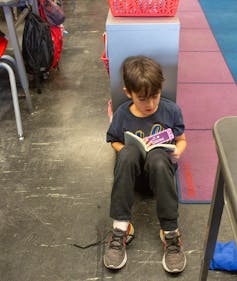

This means that it is important to foster a love for fiction in children, to promote the healthy habit of reading stories for pleasure as early as possible.

The current trend of governments prioritizing the sciences over the humanities in education runs directly counter to the evidence available. Given the benefits that verbal abilities provide in terms of success in school and in one’s career, fostering a love for stories in children should be a high priority for governments and educators.

Written by York University psychology Professor Raymond Mar and republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.