This article is cross-posted with permission from Bereskin & Parr.

The United States Patent and Trademarks Office (USPTO) has released an updated set of Eligibility Examination Guidelines to provide guidance to examiners on when to reject claimed inventions as ineligible abstract ideas. These guidelines give a sense of what computer-implemented subject matter the USPTO considers to be ineligible for patent protection.

Developing guidelines was difficult for the USPTO as the courts have provided little explanation of when patent claims are invalid for defining ineligible abstract ideas, or even what abstract idea means, and the USPTO lacks the authority to craft its own definitions. The USPTO is largely limited to telling examiners that patent claims cover abstract ideas if they cover subject matter that is similar to what the courts have determined to be abstract ideas. Given the absence of general concepts or principles for identifying the kinds of abstract ideas that are not eligible for patent protection, practitioners and applicants need to be aware of all of the Federal Circuit and Supreme Court case law on patent subject matter eligibility, and to craft patent claims with arguments in mind as to why the subject matter covered by the claims is materially different from subject matter determined to be ineligible in any of this case law.

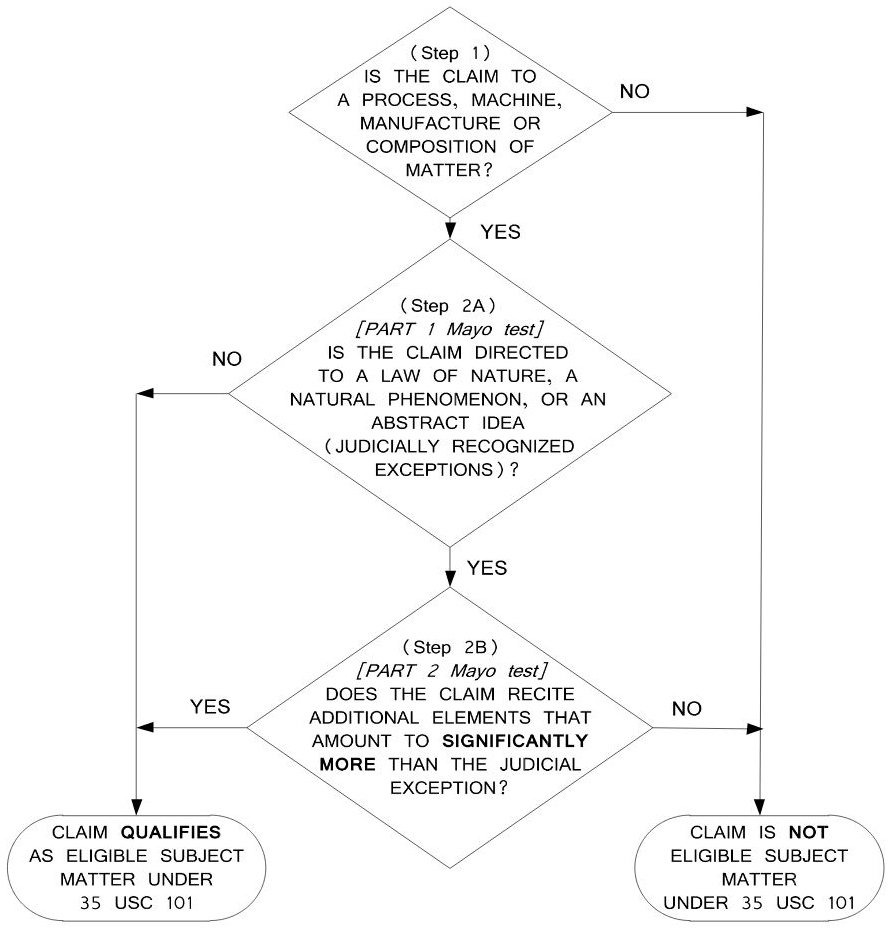

The original 2014 Interim Guidance on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility1 document (“the Guidance”) defines steps to be taken by an Examiner to assess subject matter eligibility. Steps 2A and 2B apply the two-part analysis from Alice2 and Mayo3. In step 2A the Examiner determines whether the claim is directed to a statutory exception to patent protection: a law of nature, natural phenomenon or an abstract idea. If not, then the claim is eligible for protection (although the Examiner must still determine whether the claim meets the other requirements for patentability, such as novelty and non-obviousness). If the claim is directed to a law of nature, natural phenomenon or an abstract idea, then step 2B applies and the Examiner determines whether the claim as a whole represents “significantly more”. Claims that do not cover significantly more than a law of nature, natural phenomenon or abstract idea are ineligible for patent protection and are to be rejected under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

The posting of the Guidance in 2014 provoked much comment and criticism, some critics alleging that under the Guidance virtually nothing was eligible for patent protection. The July 2015 Update on Subject Matter Eligibility4, (“the Update”) responds to these comments and criticism.

The Update provides an updated set of subject matter examples, and also divides the case law into different categories of abstract ideas, which are useful both as a credible attempt to organize the case law, and to provide insight into the USPTO’s perspective on this case law and arguments they may find persuasive. It also provides reassurance that the USPTO is addressing criticism that under the current rules post-Alice5 there is not a clear path forward for software patent applications because of the difficulties encountered with subject matter objections. The Update makes it clear that examiners should not determine a claimed concept to be an abstract idea unless the claimed concept is similar to at least one concept that either the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court have identified as an abstract idea. In other words, applicants should be able to avoid having their claims rejected, at least in the USPTO, on subject matter eligibility grounds by defining concepts in the claims that differ sufficiently from claim concepts invalidated on these grounds by the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court.

Of course, much will depend on how aggressive and creative examiners are in determining that claimed concepts they are considering are similar to a concept determined to be an abstract idea by the courts. Further, the Update makes it clear that this determination of similarity does not require evidence: examiners can ground such a rejection by merely explaining, clearly and specifically, why the claimed concepts are similar to concepts determined to be abstract ideas by the courts, and are thus ineligible for patent protection.

New Examples

In the Update, several new examples are provided in addition to those found in the original Guidance document and include:

- Transmission of Stock Quote Data – modeled after the claims at issue in Google Inc. v. Simpleair, Inc.6, (Claim 1 ineligible, Claim 2 eligible).

- Graphical User Interface for Meal Planning – based on Dietgoal Innovations LLC v. Bravo Media LLC7 (Claim 2 ineligible).

- Graphical User Interface for Relocating Obscured Textual Information (Claims 1,4 eligible, Claims 2-3 ineligible).

- Alerting System for a Catalytic Chemical Process -- based on Parker v. Flook8 (Claim 1 ineligible).

- Temperature Control of Rubber Molding -- based on Diamond v. Diehr9 (Claims 1-2 eligible). Claim 1 is the actual claim 1 from Diamond v. Diehr, Claim 2 is a hypothetical claim in the form of computerized instructions.

- Exhaust Gas Recirculation in an Internal Combustion Engine – based on technology from U.S. Pat. 5,533,489 (Claim 1 eligible).

- A method of loading System Software (BIOS) into a computer – based on technology from U.S. Pat. 5,230,052 (Claim 15 eligible).

In each example, the Update evaluates the hypothetical claims based on steps 2A and 2B, and discusses how an Examiner might determine patent eligibility for patent claims covering an analogous technology.

Example #25 – Diamond v Diehr

An interesting example in the Update is #25, since it introduces hypothetical claims modeled after the technology in the 1981 case Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981). This case dealt with a patent involving a computerized process controlling a rubber molding press. The invention offered significant advantages over the prior art at the time, as it enabled in situ temperature monitoring and automatic recalculation of the optimal cure time. This calculation involved using the temperature inputs and the Arrhenius equation, long used to calculate the cure time of rubber molding processes.

The reasoning in the Update for Diamond v Diehr differs from the reasoning provided by the Supreme Court. In the 1981 decision, the Supreme Court obliquely refers to the machine or transformation test in determining subject matter eligibility:

“A mathematical formula, as such, is not accorded the protection of our patent laws, Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U. S. 63 (1972), and this principle cannot be circumvented by attempting to limit the use of the formula to a particular technological environment. Parker v. Flook, 437 U. S. 584 (1978). Similarly, insignificant post-solution activity will not transform an unpatentable principle into a patentable process. To hold otherwise would allow a competent draftsman to evade the recognized limitations on the type of subject matter eligible for patent protection. On the other hand, when a claim containing a mathematical formula implements or applies that formula in a structure or process which, when considered as a whole, is performing a function which the patent laws were designed to protect (e.g., transforming or reducing an article to a different state or thing), then the claim satisfies the requirements of § 101. Because we do not view respondents' claims as an attempt to patent a mathematical formula, but rather to be drawn to an industrial process for the molding of rubber products, we affirm the judgment of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals.”10

In example #25, according to the Update, Claim 1 from Diamond v. Diehr involves a repeated calculation of the Arrhenius equation, a mathematical relationship held to be representative of a law of nature, and therefore Step 2A is met. Next, analyzing the claim as a whole using the Guidelines, the combination of steps taken together amount to significantly more than just the abstract idea of the Arrhenius equation (Step 2B). Thus, claim 1 in Diamond v Diehr is patent eligible, satisfying the “significantly more” step of the test.

The USPTO may have seen fit to rewrite the justification for this case to bring it into accord with the Alice framework. The Court in Diamond v Diehr determined that the structure claimed, considered as a whole, was the kind of structure and performed the kind of function the patent laws were designed to protect. In making this determination, the Court refers to the machine or transformation test to establish the patentability of the claimed invention. However, after the decision of the Supreme Court in Bilski, the machine or transformation test is no longer the definitive test, although it remains a helpful indicator of subject matter eligibility.

Categories of abstract ideas outside the scope of patentable subject matter

The US courts have provided little explanation of when and why patent claims are invalid for covering abstract ideas. Since the USPTO lacks the authority to create its own definitions, and it is difficult, perhaps impossible, to discern principles from the case law, the USPTO has instead focused its efforts on helping examiners to determine if the concepts defined in claims are similar to what the courts have determined to be abstract ideas, and are thus invalid. The Guidelines and Update construct several different categories of ineligible abstract ideas based on the case law. Each category covers many different examples, taken from the case law, of concepts defined in patent claims that have been invalidated by either the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court as abstract ideas. Clearly, patent applicants should do whatever they can to define their inventions using claim language and concepts that fall outside these categories.

These categories are the closest the USPTO gets to general concepts or principles for subject matter eligibility. These categories include the set of “judicial descriptors” associated with software based subject matter that has been identified by precedent in the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court as patent ineligible, including

- “Fundamental economic practices” including concepts dealing with the economy and commerce including contracts, legal obligations and business relations.

- Mitigating settlement risk -- Alice11.

- Mitigating hedging risk -- Bilski12.

- “Certain methods of organizing human activity” including concepts dealing with personal and intrapersonal activities including relationships, transactions involving people, social activities and behaviour.

- Managing human behaviour, specifically meal planning -- Dietgoal13.

- Advertising, marketing and sales – Ultramercial14.

- “An idea ‘of itself’” i.e. an idea standing on its own including a bare concept, plan or scheme, and

- Methods of comparing data that could be done mentally -- Cybersource15.

- Concepts relating to organizing, storing, and transmitting information – Cyberfone16.

- “Mathematical relationships/formulas” including algorithms, mathematical relationships, formulae and calculations.

- Converting binary coded decimal values to pure binary values -- Benson17.

- A mathematical formula for hedging – Bilski18.

It is difficult to find recent cases where software related patents have survived subject matter eligibility analysis by the Federal Circuit or the Supreme Court. Given the numerous examples of ineligible subject matter in the Update and Guidelines combined with the rejection statistics19 from the USPTO and invalidation statistics20 at the Federal Circuit, it is reasonable to ask whether any claims have recently survived challenge on subject matter eligibility grounds. One example outside of the scope of software subject matter is Myriad21, where the Supreme Court allowed claims for complementary DNA.

While the Supreme Court invalidated all of the claims in both Bilski and Alice; there is one case related to software subject matter that has survived scrutiny, at least at the level of the Federal Circuit: DDR Holdings v Hotels.com22.

DDR Holdings v Hotels.com23

The Guidelines discuss this case. This is the first Court of Appeal for the Federal Circuit case to uphold the validity of a software subject matter patent since Alice. In this patent, the claims were directed to managing the look and feel of an e-commerce website to provide “store within a store” functionality.

The claims in DDR covered a software solution to a problem, which, according to the judgment but not the dissent, was unique to the internet. The claims dealt with the problem of retaining website visitors at an ecommerce site and offered a solution anchored in software that addressed a challenge unique to the web. Specifically, in the prior art a user clicking on an advertisement would be taken away from the host website to the advertising merchant. The claimed invention involves presenting a hybrid page generated by the host website to include a composite of the host website and advertising merchant’s product information. The decision was based, at least in part, on the grounds that the claimed concept lacked a non-technological analog.

Takeaways

When drafting new applications for software-based inventions, it is important to keep in mind the judicial descriptors of ineligible subject matter, and to draft the claims to avoid categorization under any of these judicial descriptors if at all possible. However, it is also important to keep in mind that this area of law is in flux, and will almost certainly see significant change over the next few years. In particular, the categories of ineligible subject matter constructed by the USPTO may evolve or grow in number over the next few years as more cases are decided. Eventually, as the courts grapple with more and more cases, clear principles may start to emerge from the present chaos. One day, it may again be possible to rely on general principles to distinguish patent eligible subject matter from ineligible subject matter. At present, that day seems far distant, and for the foreseeable future it will be even more important to keep up-to-date on the latest Federal Circuit and Supreme Court precedent, mostly to know what kinds of subject matter to avoid claiming, but also to keep an eye out for the occasional beacons of hope, such as a DDR.

1 2014 Interim Guidance on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility, 79 Fed. Reg. 74618 (Dec. 16, 2014).

2 Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S.Ct. 2347, 110 U.S.P.Q.2D 1976 (2014) [Alice].

3 Mayo Collaborative Serv. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 132 S.Ct. 1289, 101 U.S.P.Q.2D 1961 (2012) [Mayo].

4 July 2015 Update on Subject Matter Eligibility, 80 Fed. Reg. 45429 (July 30, 2015).

5 Alice, supra.

6 Google Inc. v. Simpleair, Inc., Covered Business Method Case No. CBM 2014?00170 (Jan. 22, 2015).

7 Dietgoal Innovations LLC v. Bravo Media LLC, 599 Fed. Appx. 956 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 8, 2015) [Dietgoal]

8 Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 98 S. Ct. 2522 (1978).

9 Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 101 S. Ct. 1048 (1981) [Diamond v Diehr].

10 Diamond v. Diehr supra at 191.

11 Alice, supra.

12 Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 130 S. Ct. 3218 (2010) [Bilski].

13 Dietgoal, supra.

14 Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709 (Fed. Cir. 2014) [Ultramercial].

15 Cybersource Corp. v. Retail Decisions, Inc., 654 F.3d 1366, 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2011) [Cybersource].

16 Cyberfone Systems, LLC v. CNN Interactive Group, Inc., 558 Fed. Appx. 988, 993 (Fed. Cir. 2014) [Cyberfone].

17 Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 93 S. Ct. 253 (1972) [Benson].

18 Bilski, supra.

19 Robert Sachs. “Bilski Blog: Business Methods” (2015), BilskiBlog (blog), online: http://www.bilskiblog.com/blog/business-methods/.

20 Ibid.

21 Association for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. __, 133 S. Ct.2107 (2013) [Myriad].

22 DDR Holdings v. Hotels.com, 773 F.3d 1245, 113 U.S.P.Q.2D 1097 (Fed. Cir. 2014) [DDR Holdings].

23 Ibid.

Ian McMillan is a partner, lawyer and patent agent in Bereskin & Parr's Patent Group in the Mississauga Region. He is active with the Intellectual Property Institute of Canada (IPIC) and has contributed extensively to patent education in Canada. Paul Blizzard is a JD candidate at Osgoode Hall School and was a summer student in Bereskin & Parr's in Toronto. Twitter: @paulblizzard.