The Osgoode Library has purchased a modest collection of twenty-eight bookplates of various Canadian legal personages. These bookplates are of interest for biographical, bibliographical and professional reasons, and are also sure to be of interest to Game of Thrones fans for their assortment of family sigils and words, or in heraldic parlance, charges and mottoes.

A bookplate, also known as an ex-librīs (from the Latin for "from the books of..."), is usually a small label pasted into a book, often on the inside front cover, to indicate ownership. Bookplates can be decorative or plain. Simple typographical bookplates are often termed "booklabels". Typically, though, they bear a name, motto, device, coat-of-arms, crest, badge, or any motif that relates to and identifies the owner of the book. Many collectors and other bibliomanes commission an artist to design a bookplate for their personal use. The name of the owner is usually preceded by an inscription such as "From the books of . . ." or "From the library of . . .", or the Latin, "Ex libris . . ."

When attempting to determine the provenance of a book, a researcher’s best friend is the humble bookplate. No handwriting to decipher, no ambiguous ink marks, and no mysterious initials - bookplates are a comparatively clear and exact indicator of previous ownership (unless some sneaky individual inserts another person’s bookplate in a book never owned by that person - who could commit such an atrocity?).

Very often, especially before the 20th century, bookplates took the form of an individual’s coat of arms, which is wonderful, because — in theory at least — no family’s arms should be the same as any other's, and even within the same immediate family arms are distinguished from person to person by marks of cadency. If the family plays by the rules of the appropriate heraldic authority (in our case, the Canadian Heraldic Authority), then the coat of arms should point directly to a particular individual, or at the very least, a particular family. Coats of arms are described with a specific heraldic argot, and since each is — again, theoretically — unique, each description should be unique too. If you know one of the name, coat of arms, or the description of the coat of arms, you can usually logically infer the rest of the information with the appropriate resources. What’s more, many arms and crests also feature mottos (think “Winter is coming”), which not only sound heroic, but are also an important piece of information. In sum, armorial bookplates can be as exact and even more meaningful than a clearly printed name and date, and they are much more delightful to behold.

While bookplates are certainly useful to researchers, many of them are also quite stately little works of art. Here are a few choice examples from our new collection, with well-researched descriptions courtesy of our dealer Warren Baker.

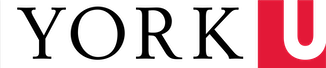

Abbott, Sir John Joseph Caldwell (1821-1893). Crest. 8.8 x 6.2 cm. Gagnon Supp.2649. Harrod & Ayearst, p. 18; Masson Coll. Vol. I, #3.

Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott Abbott was widely viewed as the most successful lawyer in Canada for many years, as measured by professional income (and when St James Street in Montreal had not yet been surpassed by Toronto's Bay Street). He began lecturing in commercial and criminal law at McGill in 1853, and in 1855 he became a professor and dean of its Faculty of Law, where Sir Wilfrid Laurier, future prime minister of Canada, was among his students. He continued in this position until 1880. Upon his retirement, McGill named him emeritus professor, and in 1881 appointed him to its Board of Governors. Abbott succeeded Sir John A MacDonald as Prime Minister of Canada on MacDonald's death in office in 1891, but held the office for only a year due to his ill health. He was our fist Canada-born prime minister. The plate was engraved by Francis Adams, Montreal engraver and lithographer, active from 1853-57. [Motto: Devant si je puis, or Forward if I can]

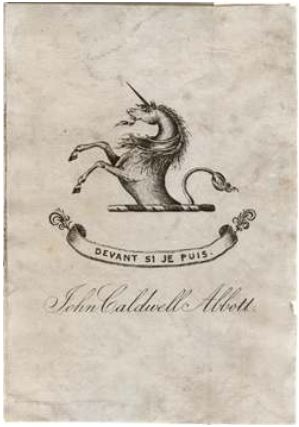

Baldwin, Dr William Warren (1775-1844). Armorial. 11.6 x 7.2 cm. Gagnon I, 4759; Harrod & Ayearst, pp. 22 & 23; Masson Collection Vol. II, #229.

According to Harrod & Ayearst, this bookplate refers to the father of Robert Baldwin. He arrived in Upper Canada from Ireland in 1799, settling first in Durham County, where he was appointed a lieutenant-colonel in the Durham militia and a justice of the peace before the family resettled in York (not Toronto). He was called to the Bar in 1803 and appointed a district court judge in 1809. He became a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1807 and served several terms as Treasurer. He was elected MP for Norfolk in 1838. His home in York (Toronto) was called Spadina House from the Indian word spadina, which means a sudden rise of ground such as that upon which the house was built. [Motto: Nec timide nec temere, or Neither rashly nor timidly]

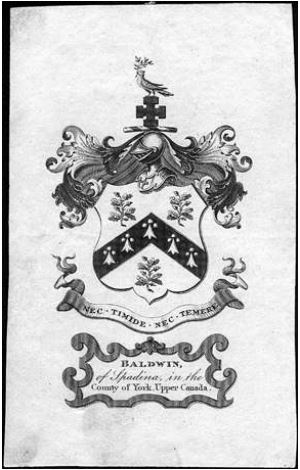

Robinson, John Beverley, Sir (1791-1863). Armorial mantling. 9.7 x 7.7 cm. Gagnon 4945. Harrod & Ayearst, p. 122; Masson Coll. Vol. XI, #1803.

John Beverley Robinson was born in Lower Canada, son of a Virginia loyalist. The family moved to Kingston, Upper Canada, in 1792. In 1799 he was enrolled in the school in York recently opened by John Strachan, and he lived in the the Strachan household until 1807. At age 16, he left to enter the study of law D'Arcy Boulton. Robinson served in the War of 1812 as a militia officer under Sir Isaac Brock, and was appointed acting Attorney General of the province. From 1818-1829, Robinson was the Attorney General of Upper Canada, and, in 1829, he was appointed Chief Justice, Speaker of the Legislative Council, and President of the Executive Council of Upper Canada. As a judge he has had few equals in the history of Canadian judicature. [Motto: Propere et provide, or Quickly and cautiously]

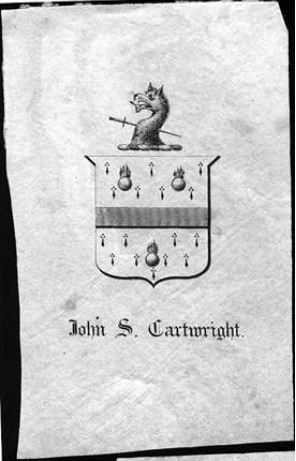

Cartwright, John S., QC (1804-1845). Engraved armorial. 10.6 x 6.7 cm. Gagnon I, 4796 who gives J. R. Cartwright; Harrod& Ayearst, p. 43, who assign his death date to 1860; Masson Collection Vol. III, #439.

John Solomon Cartwright was born in Kingston, Upper Canada, the son of Richard Cartwright and Magdalen Secord (the sister of Laura Secord). He studied law in York, UC (now Toronto) in the law office of John Beverley Robinson (whose bookplate is shown above) and was called to the Bar in 1825. He went to London to pursue further legal studies at Lincoln's Inn, but by the autumn of 1830 had returned to Kingston, where he resumed his law practice. His seriousness about his profession is shown by the large sum he was spending on legal books. In England he had probably laid out £250 for a “law library”. In 1834 he was appointed a judge of the Midland District Court; he was elected a bencher of the Law Society of Upper Canada in 1835 and in 1838 he was made a QC. He became the first president of the Commercial Bank of Kingston in 1831. He was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada in 1836 and to the Legislative Assembly of United Canada in 1841. He opposed the Union of 1840 and turned down the solicitor-generalship from Sir Charles Bagot in 1842. He died at Kingston. His great-grandson, John Robert Cartwright (1895-1979), a graduate of Osgoode Hall Law School, was Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, 1967-1970.

If you’re interested in learning more about bookplates, head to the ultimate resource at the Bookplate Society.