Over the past few months, members of the law library staff, myself included, have been preparing to reorganize our special collections.

Now, as all savvy library users know, libraries generally organize their collections and shelve their books by subject. You’re all familiar with the Library of Congress classification system, used in academic libraries throughout the English-speaking world, and have probably heard of the Dewey Decimal System, used in public libraries and school libraries. Here at Osgoode, we use the “KF Modified” Canadian adaptation, a slight variation of the Library of Congress classification developed and maintained at Osgoode specifically for Canadian law collections and widely used in law school, law firm and courthouse libraries in Canada. These library classification systems categorize books by subject and assign a specific, uniform “call number” to each book so that, theoretically at least, all books on a given topic will be found shelved together in the library. This approach facilitates the browsing of even extensive library collections, making possible those serendipitous moments when you find the book you need beside the one you thought you needed. It’s not magic, folks: it’s library science.

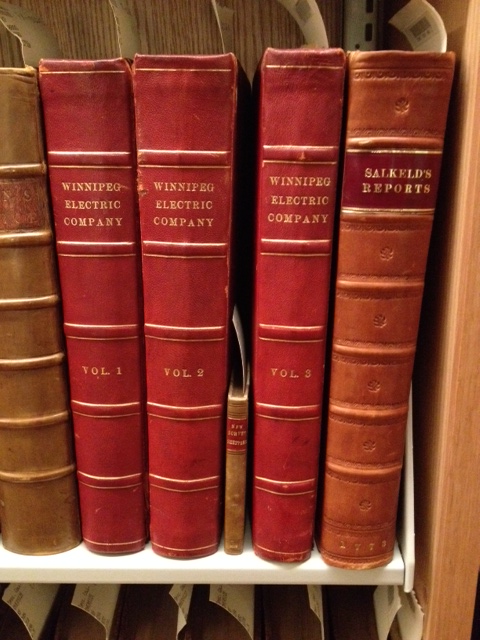

Classified systems that organize books by subject are appropriate for open collections where anyone can roam the aisles browsing the stacks for books; but for closed special collections, especially of old, sometimes rare and often fragile books, shelving the books according to subject can lead to problems. At the heart of the matter is the deep enmity that books of different sizes bear toward each other. They don’t play nicely together when sitting on the shelf. As Jane Greenfield explains in her book, The Care of Fine Books, “A large book shelved beside a small one eventually splays out.” Not only that, but “the exposed area also fades even if not exposed to strong light.” Common sense.

For maximum protection and better preservation, books are best organized by size. If books of similar size are shelved together, they lend each other support on the shelves, preventing the warping of bindings and exposing as little of their covers as possible to light. They should be shelved tightly enough that they support each other, but not so tight that you have difficulty removing them from the shelf. Naturally, since our special collections are exclusively composed of items that are either old, rare, valuable, or otherwise notable, we don’t want the bindings to warp or fade. We need to do our due diligence to take care of them, and that includes shelving them properly.

Until now, the Osgoode Hall Law School Library’s special collections had been classified and the books shelved according to subject. This was not an ideal situation for the books. Since our rare books stacks were closed and accessible only to library staff, we did not need to facilitate browsing by the public. Generally, these books will only be accessed when a patron specifically requests them, having first located them using the online library catalogue. For us and especially for the books, the benefits of shelving by size outweigh the disadvantages. So, we determined to reorganize our now extensive special collections by size.

Once this shelving scheme was decided, we needed to implement an appropriate system. Greenfield broadly categorizes books using terms that historically referred to the “format” of the book – folio, quarto, octavo, etc – which is a function of how printers folded sheets of paper to create books of different sizes. (Take a look here for more explanation and some useful illustrations, although I have to admit it’s a little tricky to understand without actually folding sheets of paper yourself). Greenfield distinguishes four sizes: miniature or small books under 10 cm; octavo books up to 28 cm in height; quarto, up to 40 cm; and folios over 40 cm. We felt these four categories didn’t quite suit our needs. In this scheme, both books 29 cm tall and 39 cm tall fall under the designation of quarto, but that still leaves 10 cm for the taller book to warp over the smaller book. We devised our own scheme that allows for not four, but ten sizes of books(!), outlined in this handy-dandy chart.

With ten sizes available to us, we only have to worry about a potential difference in size of 3 cm (1.2 inches) in any one group. Even then this 3 cm difference is unlikely to occur, as each range contains a spectrum of sizes from the minimum to the maximum heights. In group A, we have books 15 cm in height, 18 cm in height, and everything in between.

To begin reorganizing our collection by size, we first cleared a substantial section of our compact shelving, as it’s common sense and common practice to have a destination ready for your books before you start moving them. Then, we labelled our empty stacks with these letter-sizes. We know that most of our books fall within the B-D ranges, so we only allotted one stack for minis and As, while many more stacks were set aside for Cs and especially Ds. We also have a separate section of deeper shelving to accommodate books larger than D (which, when you think about it, is really no different than an oversize section you’d find in many libraries using the LC or Dewey).

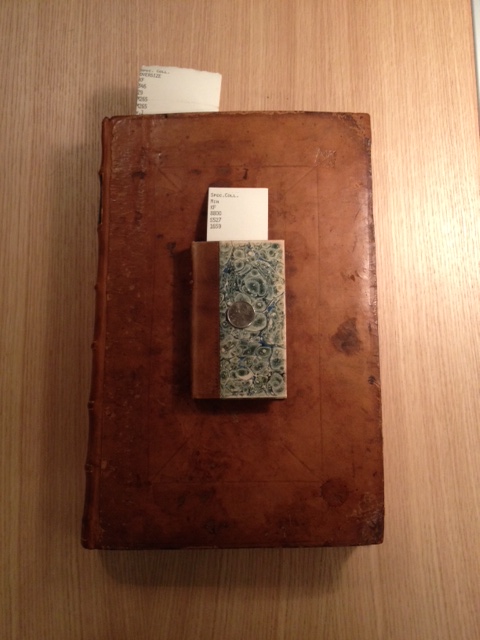

Once we had the shelves properly prepared, we needed to assign a new call number for each book based on its size. The call numbers will look something like “A-0054” or “C-0283”, those books being the fifty-fourth and two hundred eighty-third books in their size range, respectively. If there are more than 9,999 books in any size range, the letter size will become A1 instead of just A. If you see a call number with an “X” after the letter, as in “BX-0121”, it means that the book is shelved not in the compact stacks but in our rare book reading room –the Canada Law Book Rare Book Room.

Of course, we need to know each book’s size before we assign it a call number, but we can’t waste our time holding a ruler up to each volume. To speed up the process, we built ourselves a book-board (which for my money looks like it belongs in MoMA alongside Mondrian and Rothko). Behold:

I find numbers to be eccentric and challenging concepts, so I’m happy to see that someone’s nailed them down to physical reality by covering a plank of wood with the exact measurements of each letter size, all colour-coded. Now all I have to worry about are colours and letters, and I can handle that.

We have only to place a book in the board’s corner to determine its size exactly and know exactly where on the shelf it belongs. Wherever the top of the book falls, that’s its location letter. This books an “E”.

Simple, effective, and highly recommended for any library undertaking a similar project.

Finally, organizing the special collections by size has the added benefit of maximizing the space available for shelving the collection. Each shelf is always completely full, and shelves can be adjusted to uniform heights for each size category, maximizing the number of shelves in each bay of shelving. It’s a pity the stacks are closed to the public and you can’t admire the orderly elegance of the Osgoode special collections.