The York University community is hearing all kinds of messaging about restructuring these days and it's important to provide some context as to what is behind it and examples of other restructurings, like those that were forced on the City of Toronto by Mike Harris and Doug Ford that did not deliver on the promises of cost savings.

In 2023, York University's management received a report from the NOUS Group. Management did not share this $8m report with employees or unions or students and it took months of requests by the faculty association, YUFA, to receive the go-ahead to share the report with employees.

But now we can read the NOUS report and use it to contextualize current presentations and communications from deans, provosts and presidents regarding "restructuring" plans at York University. This blog post is an attempt to connect the dots between the original consultants' presentation, derivative works (e.g. "Faculties of the Future") documents being circulated at York University, and similar related restructurings at other institutions like Laurentian and the University of Alberta.

What is the NOUS Group?

The NOUS consulting group makes money by suggesting how to restructure universities. Its track record on this is very much anti-collegial -- through quiet shifting of money, resources and decision-making away from employees like professors and more into the hands of a few executives. For example, NOUS wants Laurentian to centralize more power in its Board of Governors and to gut the collegial Senate. Its suggestions at Laurentian are similar to those that it has provided for management at the University of Alberta and, now, at York University.

The NOUS Group pushes its agenda by holding up what it purports to be examples of waste: for example, by vilifying professors, as shown in a citation-less "parking grants" item in their report.

The solution, as NOUS sees it? Remove resources, services and independent decision making anywhere near the university's front line (where students are) and consolidate it around deans, presidents, chancellors, and provosts.

Any student reading this, ask yourself: when was the last time that you had a meaningful conversation with a dean about your education or the state of infrastructure like the washrooms at the university? Has the President shown up in your class to consult with you or held a town hall in which questions weren't pre-screened? Now, ask yourself if we should have more open and responsive services fielded by employees who know you best and are willing to listen to you, uncensored, and give you frank, direct answers.

Poorly-justified amalgamation won't deliver promised benefits

Central to the NOUS report is the faulty assumption that amalgamation, consolidation and "economies of scale" are not only desirable, but also necessary and that they will lead to real financial savings. NOUS hints at the faulty assumptions, albeit quietly, in the margins and small font notes of its report. I'll get back to that shortly.

The NOUS report uses terms like "economies of scale" to help justify its directions for amalgamation of resources: to achieve economies, they say, the university will need to amalgamate work units and resources. So, the amalgamation messaging is getting out there... first as part of "austerity" messaging. Now, it's part of the talk centred around "restructuring". Earlier this year, it was at Senate. Now, the Faculties of the Future brand of amalgamation is being brought to individual faculty councils, like this:

Amalgamating work units at the University is, quite simply, a bad idea. But to do it in the name of "cost savings" -- which is how it is being presented -- is disappointing.

Again, this needs to be emphasized: the drive for amalgamation is not to make programs better. It's not to improve student experience. It's not to make research thrive. Amalgamation is to achieve "cost savings."

But we don't need to imagine that it's just a bad idea at a university like York. It's bad at other universities and in industry, too. Nobody can argue, with a straight face, that consolidation in the telecomm or grocery markets has been good for consumers. Likewise, the risk in making faculties bigger and amorphous is that more and more students will "get Yorked."

So, let's look at some examples of how amalgamations have gone badly, whether it's here in Toronto or further afield in the corporate world.

Amalgamation is bad: from the City of Toronto to Boeing to HP-Compaq

When businesses choose or are forced to merge, amalgamate, or centralize, it is often with the promise of "efficiencies" and "economies of scale". But universities, like (and different from) businesses, are complex, dynamic systems, with lots of moving, poorly understood parts. The promise is often empty and nothing more than wishful thinking. It is not, in my opinion, worth the risk that wholesale restructuring poses to an institution, when smaller, more targeted changes can be put forward, tested and evaluated.

But, here in Toronto, we have two very good examples of how amalgamations don't deliver of the cost savings promised. The first example is the Harris-era amalgamation of Toronto: "Promised savings of $300-million per year never materialized." (source and another). Loss of local representation, increases in bureaucracy are also cited as problems that have arisen as a result of the amalgamation. And, more recently, the forced restructuring of Toronto's wards has led to increased staffing budgets and other complaints.

We should also heed the warnings from the corporate world. Outside of Toronto, the tragic story of Boeing's downfall really began with its merger with McDonnell-Douglas merged, the new company was predicted to improve its market position, to allow for significant costs savings and operational efficiencies, as well as an expanded product line. Papers were published that stated that there would be "no merger effect in the long run." As we now know, the amalgamation boosters were wrong.

The nature of Boeing fundamentally shifted from a company that valued individual employee expertise and group knowledge to a centralized, top-down, management-driven monster that punished experts and led to criminal fraud tied to airliner crashes, a space capsule that stranded astronauts, and even a door panel being sucked out of an airplane mid-flight.

Another important example for corporate amalgamation gone wrong is HP-Compaq merger in 2002. While both HP and Compaq were nominally "computer" companies, they had different underlying cultures and histories. Notably, HP was guided by the famous "HP Way". Compaq had no equivalent. The prescient warnings about the merger were ignored and the result was the decline of the amalgamated company. The merger led to cultural clashes, a worsening of employee morale, worse operational performance and worse financial performance. (source) The merger was not sole reason for the decline -- HP had wrongly jettisoned valuable core assets previously -- but was simply another poor decision in corporate restructuring that led to long term negative consequences.

At Boeing and HP, amalgamation made the resulting companies less capable, not more capable. As we now know, the short-term gains were not worth the long-term losses. Promised "synergies" and "cost savings" never materialized. And while NOUS doesn't appear to suggest external mergers, it does strongly advise for internal mergers within universities. And, just like with the examples provided here, York University managers are promising synergies. (pg 18 of the draft Faculties of the Future document) Those "synergies" never appeared after Boeing-McDonnell-Douglas or HP-Compaq mergers, so why should we expect differently here at York if two faculties are amalgamated together? The risk in proposed faculty mergers, just as we've seen in the corporate world, is the loss of both actual employees and also their ability to leverage their individual expertise within their current work units.

"These are not direct cost savings" is the quiet truth in the NOUS report

The money paid to NOUS is real. We gave them eight million dollars. Eight million that could have gone into student scholarships, classroom upgrades, and more resources to protect employees from violence encountered during night shifts.

Instead, we got a poorly justified promise of a few more million dollars in possible savings. They made sure to qualify their report with statements like "These are not direct cost savings". It's right there, in the their presentation, in black and white:

Furthermore, the report states that there would be $4.5m in additional revenue from grants. As any researcher in Canada knows, the grant system is effectively a lottery and the odds are getting worse every year. But how did NOUS come up with that value? It blamed faculty for "parking grants" outside the university and blamed staff for causing "pain points" in the grant process. But if the University adopted the NOUS recommendations then the pain points would disappear and grant revenue would increase.

This is, frankly, insulting and does not reflect my experience or the experience of many (most?) of my faculty colleagues. The staff that I've worked with on grant applications are experts and bend over backwards to make the process as seamless and efficient as they can. The NOUS report does not reflect the reality of how staff currently work with faculty on grant applications and management.

researchers experience service improvements." From page 19 of the NOUS report.

Worse, grant money doesn't go into the general coffers of the Unviersity. It goes into dedicated research accounts held by individual professors. Some of it sometimes makes it into general coffers via overhead skimming, but it doesn't account for much, and it certainly doesn't apply to all grants that come in from the outside. I wonder how much central management would like to increase overhead and find other mechanisms to siphon off grant money from individual faculty.

So, the truth is that we sunk $8m into a powerpoint presentation that will be used to justify cuts and amalgamations. And the "cost savings" that NOUS touts or that we're hearing about in the "Faculties of the Future"? We will likely never see them. Because they weren't real in the first place.

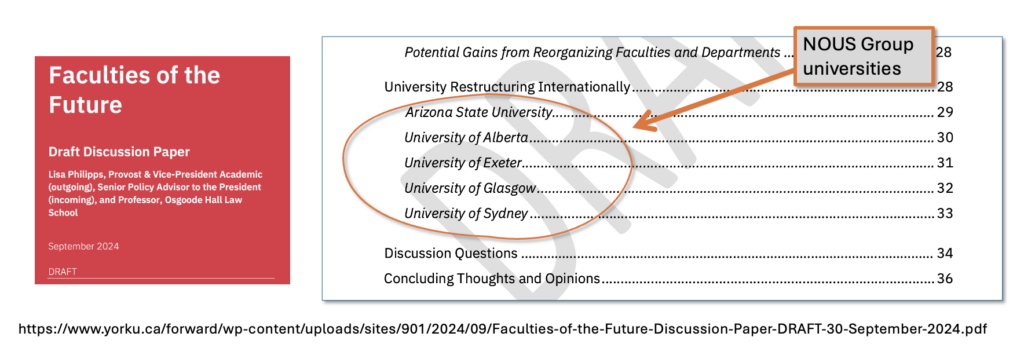

The NOUS Group has pitched the amalgamation plan before. Two of its targets, the University of Alberta and the The University of Sydney were shown as examples in the YorkU's Faculties of the Future presentation, as shown above.

In fact, all of the examples that are being given to the York University community have NOUS group's fingerprints on them, including Arizona State University, The University of Alberta, The University of Exeter, The University of Glasgow and The University of Sydney:

Notably absent from the restructuring list is Laurentian University. But, it's important to point out that Laurentian is also a target of NOUS group restructuring.

If we're going to have a discussions about merging faculties then it's important that we don't pick from the same source (NOUS). We should be looking at multiple examples and we should be putting up failed amalgamations front-and-centre to ensure that, if we go down this route, we don't repeat mistakes of the past.

What's next? Restructuring losses

But, because decision makers will feed each other this PowerPoint presentation and then will create other PowerPoint presentations that will be disseminated down to middle management for implementation, the narrative will grow that amalgamations will lead to a the promised cost savings.

And, remember, that even the consultants from NOUS told us, in the pages of their own report, that the savings aren't real.

We will hear summaries of those orders and some pretty graphs. Faculty and staff will be told that we need to get down to business. Cuts will start. Colleagues will be "let go" or be given buy-out packages like the Voluntary Exit Program.

Restructuring will be rolled-out. The University will lose institutional knowledge embedded in those employees. But the managers in the board rooms won't notice. The AC will continue to work in their offices. Their washrooms will be cleaned. And students will mill about in green space below. But the effects will be felt, later, just like they were at Boeing, HP-Compaq, and the City of Toronto.

Conclusion

The arguments being made for amalgamation of work units and for shifting and shedding of workers at York University are not grounded in evidence -- it is based on wishful thinking. The risk to the University, as a whole, and to individual faculties and work units, is real and is not justifiable.

Value for money? The NOUS report wasn't worth it. And neither it, nor any derivative works that get disseminated to the York University community should be used to justify restructuring or any other changes. This is because the underlying assumptions are faulty -- even NOUS admitted it when they stated "[these] are not direct cost savings." Students, staff and faculty should push back and put real alternatives on the table -- alternatives that reflect the strengths, needs and realities of individual faculties and on-the-ground employees and students -- because, as we'e seen elsewhere, the end result of the forced restructuring that YorkU management is pushing likely won't be what is promised.

Edits

- Sept-October,2024: major re-write primary focused on comparisons like Toronto and HP-Compaq.

- Nov 16, 2024: Compaq history video added. (Source)

- Dec. 1, 2024: typo near the parking grants item fixed. Gateway (U of A) link fixed and added. University of Sydney article re-linked.

James Andrew Smith is a Professional Engineer and Associate Professor in the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department of York University’s Lassonde School, with degrees in Electrical and Mechanical Engineering from the University of Alberta and McGill University. Previously a program director in biomedical engineering, his research background spans robotics, locomotion, human birth and engineering education. While on sabbatical in 2018-19 with his wife and kids he lived in Strasbourg, France and he taught at the INSA Strasbourg and Hochschule Karlsruhe and wrote about his personal and professional perspectives. James is a proponent of using social media to advocate for justice, equity, diversity and inclusion as well as evidence-based applications of research in the public sphere. You can find him on Twitter. Originally from Québec City, he now lives in Toronto, Canada.