Given the politicization of COVID-19, a new and ground-breaking book offers insights on the personalities of diplomats, and the risks that those with certain mindsets introduce on a world stage. The author considers the perils of having political leaders with a depressive temperament.

Peter S. Jenkins, an adjunct faculty member at Osgoode Hall Law School, is an expert on digital media and the law. However, he turned his attention to a highly original area a few years ago – the mindset of political leaders – and the resulting book, War and Happiness – The Role of Temperament in the Assessment of Resolve (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), could not be timelier. Although it was published before the pandemic, key insights can be gleaned about the politicization of COVID-19 and the response to the global crisis by certain world leaders.

Canada and the world need visionary and inspirational leaders more than ever, many would argue. With the plight of COVID-19 patients and their families, healthcare systems and resources stretched to the limit, and with the global financial disruption that began last March, it feels as if we’re living through a dreadful combination of the Great Depression and the Spanish Flu. “Unprecedented” no longer suffices.

Jenkins’ desire to investigate cognitive biases in international relations is well-timed. He is a seasoned academic who has presented his research papers around the globe, including at the University of Oxford, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Beijing Normal University.

Lesson 1: Leaders often act in very odd ways prior to war

In this 16-chapter, 378-page book, Jenkins dug deep into the British Hansard and the U.S. Congressional Record; he examined four crises leading up to the First World War; the appeasement of Nazi Germany; Pearl Harbour; the Korean War versus the Gulf War; and much more.

War and Happiness offers a fulsome analysis of empirical data, from psycholinguistic text mining and semantic analysis of debates, speeches, statements and memos to detailed case studies of the origins of twelve wars with Anglo-American involvement from 1853 to 2003.

In analyzing these many separate events, Jenkins’ first realization was one commonality: leaders often act in bizarre ways leading up to crises. For example, Jenkins notes that, less than 48 hours before the Germans invaded Poland prior to World War Two, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared that he was more worried about getting the Poles, not the Germans, to be reasonable.

The 1982 Falkland Islands War, led by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, is another perplexing event that Jenkins unpacks, as is American involvement in the Vietnam War, which caused a total of more than 1.3 million deaths.

The 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, “Operation Iraqi Freedom,” spearheaded by American President George W. Bush, in search of weapons of mass destruction that never materialized, is another example of unwarranted conflict that Jenkins cites. Over 100,000 Iraqi civilians were killed during the resulting Iraq War, which lasted until 2011.

Jenkins’ book is filled with many such historical gems – events that have left scholars scratching their heads for years. Most academics point to geopolitics and power plays as the root cause of conflict, but Jenkins has unearthed a different and novel commonality: the leaders’ mindset.

Jenkins argues depressive temperament at heart of issue

War and Happiness suggests that leaders, politicians and diplomats who have depressive temperaments will tend to underestimate the resolve of their state’s adversaries and overestimate the resolve of its allies, while the converse will occur when those individuals have non-depressive temperaments.

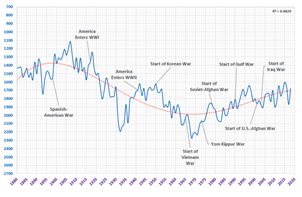

The chart below illustrates the annual frequency (per million, inverted) of sadness words in the U.S. Congressional Record (1880–2018) as a way of measuring the temperaments of politicians over time.

“The emotional climate of a state’s national legislature changes significantly over the long term in response to exogenous factors, creating a greater risk of the outbreak of war being caused by the overestimation or underestimation of its adversary’s resolve,” Jenkins explains.

Clearly, Jenkins is in his element in history. As a result, War and Happiness has received acclaim. “Jenkins’ rare combination of psychological theorizing and archival research in several countries and time periods yields a fascinating new take on the central question of when states overestimate or underestimate others’ resolve. The biases that leaders and elites fall prey to appear to vary with their emotional states and senses of well-being, factors that most scholars have ignored,” said Columbia University’s Robert Jervis, a leader in the study of the psychology of international politics.

To learn more about Jenkins, visit his profile page. To learn more about the book, visit the publisher’s website. You can also watch a short video about it.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch; watch our new video, which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity, such as Artificial Intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic, a glimpse of the year’s successes.

By Megan Mueller, senior manager, Research Communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca