Two psychology profs investigate coping mechanisms during the pandemic, and discover that people are consuming more alcohol, particularly if they’ve lost income; they’re drinking alone and feeling isolated; and those with children are using alcohol to cope with stress. Knowing this could help healthcare practitioners create better, more tailored and evidence-based interventions.

The pandemic has brought with it a profound disruption of daily life; introduced an unprecedented level of fear, anxiety and uncertainty about health risks, job loss and childcare; and left many searching for escape in the form of self-medication.

Psychology Professors Jeffrey Wardell and Matthew Keough co-led a team of researchers whose members included researchers from the University of Toronto and the University of Manitoba, as they investigated alcohol use, solitary drinking and alcohol problems during COVID-19.

The findings of this research, published in Alcoholism Clinical & Experimental Research (2020), paint a vivid picture of people turning to alcohol as a coping mechanism, particularly if they were feeling depressed or socially isolated, or if they had young children in the household. People who lost income were also drinking more heavily, and people who lived alone were drinking more often by themselves.

“Studying this phenomenon will help healthcare practitioners to tailor coping-based interventions toward individuals at risk for drinking to cope during the pandemic,” Wardell explains. These interventions could possibly have a wide application in a variety of addiction and mental health settings.

This is Wardell and Keough’s area of expertise. Wardell is a registered clinical psychologist with specialization in the assessment and treatment of addictive behaviour. Keough is a clinical psychology researcher and Chair of the Addiction Psychology section of the Canadian Psychological Association.

The timing of this new research was key. In the early spring of 2020 during the first wave of COVID-19, news reports were just beginning to emerge indicating that people may be turning to alcohol as a way of managing the stress.

Pre-pandemic research suggested that understanding the varied, individual reasons for drinking are important to better recognize the association between distress and alcohol use. It also found that individuals who drink as a way of coping are at heightened risk for alcohol problems.

Wardell and Keough’s original study builds on this existing research, adding a whole new dimension related to the pandemic.

Surveyed 320 adults across Canada

The objective of the study was to look at coping-motivated pathways to alcohol use and problems during the early stages of the pandemic.

The research team recruited participants via Prolific, an online crowdsourcing platform, and was able to survey 320 adult drinkers across Canada. Participants were 55 per cent male, 45 per cent female, and the average age was 32. They were asked about health anxiety, income loss, living alone, depression, living with a child under 18 years of age, and more; as well as how they were using alcohol during and before the pandemic.

The participants reported on their alcohol use, alcohol problems, and their drinking patterns over the past 30 days, covering a time period beginning less than a month after the pandemic was declared and emergency public health measures began to go into effect.

Findings tell a unique and complex story

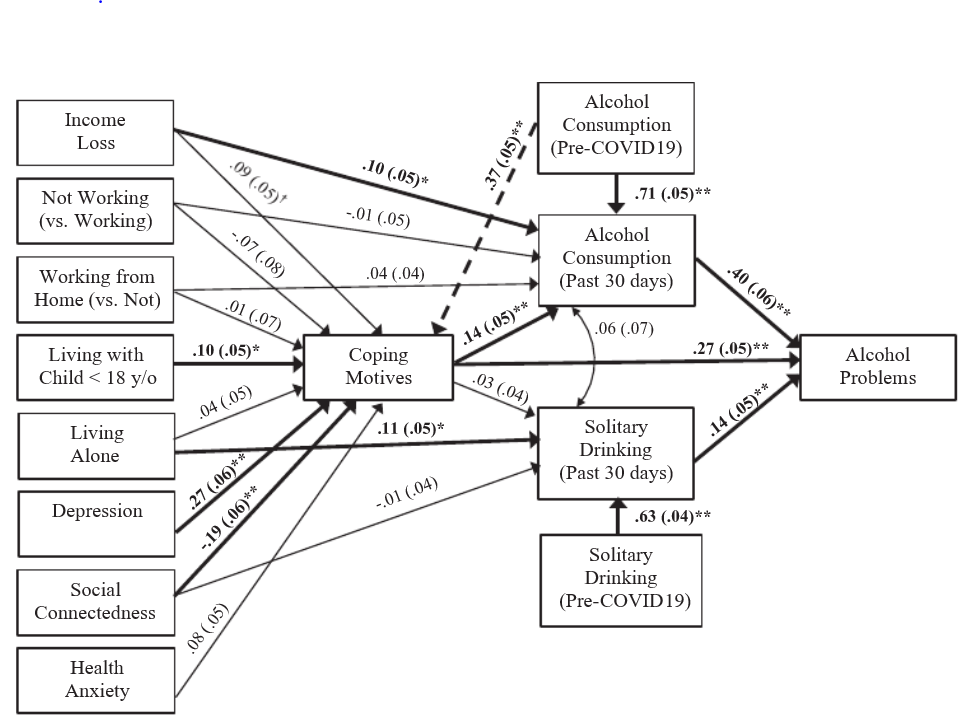

Given the large number of variables, the findings of this research are complex and comprehensive. They provide a striking new picture of how people are coping during the pandemic. The key points follow:

Drinking frequency and solitary drinking on the rise: The average drinking frequency was slightly higher than normal (pre-COVID), although the average number of drinks consumed per occasion was slightly lower than normal. Solitary drinking – an indicator of problem drinking – was more common during COVID. The percentage of solitary versus social drinking time increased from an average of 30 to 40 per cent to an average of 40 to 50 per cent.

Depression, lower social connectedness and anxiety: Most participants reported mild to moderate depression. Greater depression and lower social connectedness led participants to drink as a way of coping. Seventeen per cent reported severe health anxiety, although this wasn’t associated with drinking alcohol to ease the anxiety.

Loss of income had grave effect: Not surprisingly, most participants experienced a disruption in their work. Relocation to a home office did not affect alcohol consumption. However, for those whose income declined, the effect was grave: For over 40 per cent of those surveyed who lost part of or all their personal income, this led to more drinking. In other words, income loss had a significant, direct association with 30-day alcohol consumption.

Parents with children under 18 in the home drink more: Most participants lived with other people, not alone. Of those who had children, the average age of the child was young – five years of age. Having a child under the age of 18, who’s living at home, led participants to drink as a way of coping.

This new research will inform targeted interventions to help people cope with the pandemic without turning to alcohol. Coping-based interventions will likely also be beneficial for individuals experiencing other forms of addiction and mental health problems.

The academics, meanwhile, press for more research. “Our findings highlight the need for longitudinal research to establish longer-term outcomes of drinking to cope during the pandemic,” says Keough.

To read the journal article, visit the website. To read a media release on this visit the website. To watch a video interview with Wardell, go here. To learn more about Wardell, visit his Faculty profile page. To read about Keough, see his Faculty profile page.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch; watch our new animated video, which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity, such as Artificial Intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic, a glimpse of the year’s successes.

By Megan Mueller, senior manager, Research Communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca