A biology Professor and York Research Chair undertook a compelling study on iron overload and insulin that could inform future approaches to heart health and diabetes… ultimately, improving patients’ health outcomes. York U is leading in this area of research.

Iron is an important component of hemoglobin, the substance in red blood cells that carries oxygen from your lungs to transport it throughout your body. However, it has an often-underestimated downside: it plays a role in cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes and more. For example, an abundance of iron can contribute to heart failure.

A groundbreaking new study, led by science Professor Gary Sweeney, examined the impact of iron overload on insulin sensitivity. The study, funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Heart & Stroke Foundation of Ontario, involved experimental work by PhD student James Jahng. It was undertaken in collaboration with the University of Ottawa and Ryerson University.

The researchers made a startling discovery, published in EMBO Reports (2019), that could affect future approaches and treatments for patients with heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

From left: Gary Sweeney and James Jahng

Sweeney (York Research Chair in Mechanisms of Cardiometabolic Diseases) and Jahng (recipient of CIHR’s Frederick Banting & Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship) sit down with Brainstorm to discuss the research and its far-reaching ramifications.

Q: What were the objectives of this research?

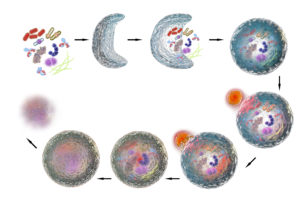

A: Autophagy is a cellular process: each cell has its own quality control mechanism so that if there’s some stress, some potential damage to the cell, then autophagy is induced to deal with that problem. It’s like a self-protective process that is able to turn on when stress occurs, and protect the cells in your body when necessary.

We wanted to test the regulation of autophagy by iron, and how it affects insulin-stimulated metabolism.

This research could lead to new treatments in metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, obesity and heart disease

Q: This is, in many ways, a continuation of your work to date, Professor Sweeney.

A: Yes. We have previously examined the importance of autophagy in regulating metabolism. This brings everything together, but this time in James’ paper (Jahng is the first author in this research article) we are looking at the direct effect of iron.

Q: Why focus on iron?

A: The reason we were looking at iron is this: in patients with diabetes and obesity, a lot of them actually have high levels of iron. There are also many genetic diseases of iron overload, which you may have heard of, such as thalassemia. Most of these patients die from heart failure, cardiomyopathy. That’s largely the result of severe iron overload.

It’s also well-established that in diabetes and obesity, there’s an increase in iron levels.

“York has a strong reputation. We now have a good cluster of researchers working in metabolic disease. This makes York a very strong leader in this area.” – Gary Sweeney

Q: How did you go about the work? Please describe the methodology and the timelines.

A: Over the last two years, approximately, we treated cells with a high dose of an iron solution for a 24-hour time period, then analyzed the results.

Q: What was the main finding? Anything unexpected?

A: The main finding is that iron caused insulin resistance in the muscle cells. It’s very simple but a strong finding.

It was a little bit unexpected because of the mechanism. When we looked deeper, we found that the cell seems to detect iron as a stress, and our data showed that there was an initial increase in this process of autophagy. But over time, after 24 hours, the iron had completely inhibited autophagy. That’s where we made the key link to iron overload stopping autophagy.

This was a very striking observation. The data was so clear. The dramatic effect we observed was somewhat unexpected.

“There’s exceptional research being undertaken here. The infrastructure, academic expertise and equipment are all superb.” – James Jahng

Q: What are the ramifications? How might this research one day benefit patients?

A: It could benefit patients in many ways. First, it could bring attention to the potential impact of high levels of iron on metabolic health. This has been known for decades, but it’s underappreciated. People know it occurs, as a small contribution, but research like this shows that we really must be careful when we consider the effects of high iron in the diet, ultimately in the body, on metabolic health. People could be more aware of iron status, and perhaps control that by dietary or pharmacological approaches.

Autophagy is a self-protective process that can switch on when stress occurs, and protect the cells in your body when necessary

There are a lot of pharmaceutical companies interested in drugs to manipulate autophagy. For example, there’s one, hydroxychloroquine, which is in clinical trials for cancer treatment right now.

As far as I know, there are no autophagy-targeting drugs in the pipeline for metabolic health. But I think this paper would suggest that one day it might be advantageous to consider autophagy-based therapeutics in treating metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity and heart disease.

Q: These results made the research very attractive to a publisher.

A: Yes, these strong results led to publication in a journal with high reputation. Being accepted for publication in a journal like EMBO Reports was fantastic not only because of the journal’s impact factor, but also because of its worldwide reputation in the scientific community.

Q: Is York U a leader in this area?

A: York has a strong reputation, yes. In terms of cardiovascular research, which has been one of the strategic priorities at York, we now have a good cluster of researchers working in metabolic disease. There’s exceptional research being undertaken here. The infrastructure, academic expertise and equipment are all superb. This, collectively, makes York a very strong leader in this area.

To read the article, “Iron overload inhibits late stage autophagic flux leading to insulin resistance” (EMBO Reports, 2019), visit the website. To learn more about Sweeney, visit his Faculty profile page. To learn more, visit the Sweeney Lab.

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York, follow us at @YUResearch; watch our new animated video, which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity such as artificial intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic for a glimpse of the year’s successes.

By Megan Mueller, senior manager, research communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca.