Creative Shifts proved that creativity is alive and well at York University's School of the Arts, Media, Performance & Design (AMPD), despite the challenges of the pandemic.

The November 2020 event brought together graduate students from across AMPD to share stories of transforming their research and creation projects in response to the COVID-19 restrictions.

“We want to think together across the arts,” said Laura Levin, AMPD’s associate dean of research, during her introductory remarks at the Creative Shifts event. “We feel this is vital for understanding the array of methods that this moment might be opening up. And we also want to think together about how we might support one another in this very unusual year.”

Despite the challenges of working alone with little opportunity for the usual cross-pollination that takes place in hallways, studios and around water coolers, these shifts led to fruitful research experiments and unexpected discoveries in artmaking.

The event, co-organized by Levin and Sunita Nigam, an AMPD postdoctoral researcher, offered wonderful stories and fascinating insights about creating.

A workshop reckoning and pivot

For Scott Christian, a master's student in music composition, the pandemic necessitated turning around a carful of actors and returning to Canada from a New York state park in mid-March.

His off-Broadway workshop of Dead Reckoning, co-created with director and lyricist Lezlie Wade, had been cancelled due to public health closures.

Christian then received funding to film 30 minutes of the piece and present it online. The video launched in October 2020 and has been seen by more than 2,000 people.

The camera as a dance partner

“If we were going to present a developmental workshop for an audience,” said Christian, “we might hit 100 people. So, the fact that we were able to create something that reached 2,000 people this year feels like a real victory.”

The camera also became a new collaborator for Meera Kanageswaran, a master of fine art student in dance, as she transitioned to a filmed version of her Bharatanatyam choreography, documenting this Southern Indian dance form.

“In Bharatanatyam,” said Kanageswaran, “we use facial expressions and movements of isolated body parts. The dancers adjusted pretty quickly to adjusting their respective cameras to focus different body parts – either their face, their feet, or their hands. I think the camera now has become a dancing partner, not just a documenting device, and that’s something I would like to retain in my practice.”

She notes the initial trouble of finding rehearsal space for each dancer to rehearse in, but reflected that this led to exploring other forms of physical expression. “Bharatanatyam uses strong footwork, which produced some unhappy neighbours. That resulted in us changing our choreography a little bit.”

Unintended basement collaborations

Ella Dawn McGeough, a PhD student in visual arts, was nearly an unhappy neighbour when her landlord proposed turning their basement into an extra apartment amid the pandemic.

She notes the initial trouble of finding rehearsal space for each dancer to rehearse in, but reflected that this led to exploring other forms of physical expression. “Bharatanatyam uses strong footwork, which produced some unhappy neighbours. That resulted in us changing our choreography a little bit.”

Unintended basement collaborations

Ella Dawn McGeough, a PhD student in visual arts, was nearly an unhappy neighbour when her landlord proposed turning their basement into an extra apartment amid the pandemic.

More than just a storage space, the basement was a generative place to create in the first few months of the pandemic before she returned to her studio at York University.

“The basement’s floors had long been a feature of fascination,” said McGeough, “a chaotic mystery of poorly poured layers of uneven concrete, the buckle and bend and fragmented sections of exposed dirt.”

She could even spot 30-year-old paw prints from a resident cat, Charlie. The basement was never made into an apartment and these non-human entities that she discovered in her art spaces over the last year became, in her words, “unintended collaborators, but I was also thinking of them as viewers.”

Taking theatre to Zoom

For Lisa Marie DiLiberto, a PhD student in theatre and performance studies, these broader audiences have become a recent focus of her work engaging the imaginations and aspirations of young people in her role as artistic director of Theatre Direct.

“One of the questions I had at the beginning of this pandemic,” said DiLiberto, “was how can theatre help young people heal through this traumatic experience of living through the pandemic through these last few months?”

One of her answers was Eraser: A New Normal, a digitally touring and Zoom-produced show that touches on issues that young people are facing in the pandemic.

The show’s digital nature has led to a broader and more geographically diverse audience. “[We’ve] reached audiences across the country or internationally, whereas that might not have been such an easy possibility to begin with,” said DiLiberto.

Accessible code illuminates environmental content

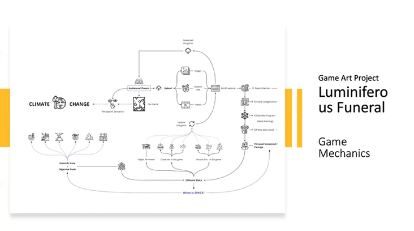

Sarah Vollmer and Racelar Ho, PhD students in computational arts, have shifted original research-creation plans by expanding the participatory scope of their virtual reality project Luminiferous Funeral, which discusses the invisible erosions brought on by climate change.

Vollmer and Ho have used tools like Google Collab and Miro to make their code accessible and allow participants to submit their own environmental content to Luminiferous Funeral.

“The original point,” said Ho, “was to break through the privilege of museums and galleries, so we tried to make our work more digital and flexible so audiences could participate in our work as content generators.”

The two have found more time to write about their work, which led them to present on how they handled their constant flow of climate data and content at a conference on information and online environments.

“That work transfers immediately into the pandemic state,” said Vollmer. “So, we’ve been able to help in ways that we didn’t think we could.”

Using augmented reality to situate artifacts

After initial setbacks in her PhD work, Lia Tarachansky, a PhD student in cinema and media studies, developed her research interests through a newly created Mitacs grant supporting her Toronto-based augmented reality (AR) project in the historic St. John’s Ward. Archeologists uncovered the artifacts in 2015 and transported them to London, Ont. Tarachansky hoped to use AR to situate them back home.

COVID-19, though, has continued to alter the project. “Through a series of trial and error I was able to get a 3D scanner from [CMA professor] Dr. Caitlin Fisher,” said Tarachansky. She then scanned artifacts like a hat block (mould), a memorial plate of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and a children’s doll, which will allow her to place the digital copies in Toronto via AR.

The current social challenges are just as serious as the technical ones and have led to important discoveries about the nature of research, something that is all too often taken for granted as an autonomous endeavour.

“Without access to people, without the ability to interact and brainstorm together,” said Tarachansky, “working in isolation is bringing out the understanding of how collaborative academic research is, even when pre-COVID we used to think it was very isolated and self-driven.”

Levin agreed that events like this one aimed to bring makers and thinkers together to support each other. “Many of us are having conversations within our own disciplinary silos right now,” said the associate dean, “about how to wrestle with the conditions of distanced research, both intellectually, creatively, and in other modes.”

Judging by the lively discussion that followed the presentations, the event met its goal of sparking new connections across AMPD.

By Thomas Sayers, MA student in theatre & performance studies at AMPD

Courtesy of YFile.