The panel focused on reconciliation in action and was the University’s keynote event leading into a full day of activities created for the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The day concluded with a symbolic evening illumination in orange light of the Ross Building on the Keele Campus and the Glendon Manor on the Glendon Campus.

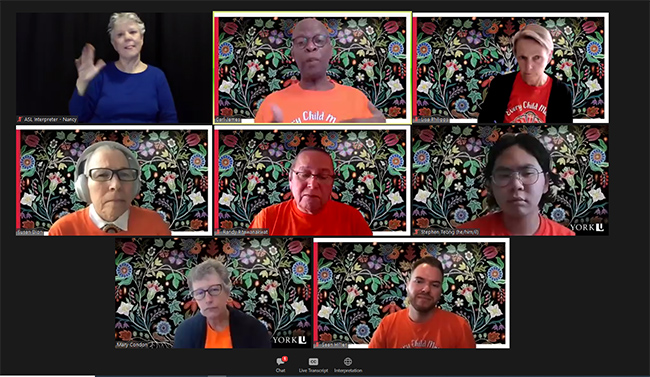

More than 700 faculty, staff and students attended York University’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation virtual panel, “Reflections on Truth and Reconciliation,” which took place Sept. 30.

Faculty of Education Professor Carl James, senior advisor on equity and representation and the Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, served as the panel moderator, which was presented by York University President and Vice-Chancellor Rhonda L. Lenton and Vice-President of Equity, People & Culture Sheila Cote-Meek.

In her opening remarks Lenton spoke about the importance of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in understanding and acknowledging Canada’s colonial practices, which had a devastating impact on Indigenous Peoples. She said that it was essential for universities across Canada to reflect on their role as part of a colonial system of education and their responsibility to advance Indigenous scholarship, knowledge mobilization and action that will help move the country towards reconciliation.

Cote-Meek, who is Anishinaabe from the Teme-Augama Anishnabai, spoke about her own experience with the intergenerational trauma that was the result of Canada’s Residential School System. “This is an important day to Indigenous Peoples as well as all Canadians, settlers and visitors to this land,” she said. “While this day marks an important step towards reconciliation, it is also a stark reminder to Indigenous Peoples of the many children who were forcibly removed from our communities and the resulting violence and trauma experienced in the Indian Residential School System.

“This past summer has been particularly difficult as unmarked graves of hundreds of children were located on various sites of residential schools across this country. Based on death records, more than 4,100 children died at residential schools,” she said, noting that the true total is anticipated to be much higher.

Cote-Meek’s own grandfather was forced to attend the St. Peter Claver School for Boys in Spanish, Ontario. “He survived but never spoke of his experiences there and it wasn’t until years after his death that I learned of his attendance. When I did, it answered so many unanswered questions for me that I did not understand about my own family.

“It is important that non-Indigenous people in Canada confront this history and understand the systems from which they benefit and begin to understand how we are all in relation to one another and the land. So today, we honour the victims, those who did not return home and we honour the survivors, including those who are descendants of survivors. We acknowledge your strength and resilience.”

After Cote-Meek’s remarks, Zoey Roy, an Indigenous artist, spoken word poet and a PhD student in the Faculty of Education, presented an original spoken word poem before a two-minute period of silence prior to the start of the panel.

Participating in the panel were: Associate Vice-President Indigenous Initiatives and Faculty of Education Professor Susan Dion; Provost and Vice-President Academic Lisa Philipps; Sean Hillier, Indigenous Council Co-Chair and assistant professor and York Research Chair in Indigenous Health & One Health; Osgoode Hall Law School Dean Mary Condon; Randy Pitawanakwat, manager, Indigenous Student Services; and Stephen Teong, interim president, Glendon College Student Union.

Each panellist was asked to answer one of five questions: How/where do you see reconciliation in action? What have you learned from the conversations happening and/or not happening about reconciliation? What actions have you taken or want to take in service of reconciliation? How do you understand your responsibility to participate in accomplishing reconciliation? Reflecting on your position within the York University community, what do you hope a focus on reconciliation will accomplish?

Dion was the first to respond to the question: What have you learned from the conversations happening and/or not happening about reconciliation?

A Lenape and Potawatomi scholar with mixed Irish and French ancestry, Dion said that while she was encouraged by the interest in truth and reconciliation, she has persistent concerns. “What do Canadians her when we speak? I know that conversations are difficult. They require a rethinking of the story we tell ourselves about what it means to be Canadian. I find that the desire to make the conversations all about you and the feelings for us – feeling sorry for us or feeling bad for Indigenous Peoples and how much you want to help us, but I have to say that sometimes these conversations can be very frustrating and tiresome, even exasperating,” she said.

In contrast, Dion said that her mother, who had been denied access to her language and cultural practices because of the intergenerational impact of her parents’ time in residential school, provided Dion and her siblings with what they needed to do the work of gathering, sharing and initiating conversations about being Indigenous. These conversations, said Dion, have focused on recuperating knowledge, participating in and learning from each other and the land. Important conversations, she said because they are about recognizing knowledge and story, cultural practice and ceremony.

“On this National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, conversations about the impacts of residential schools have to happen. They have to happen respectfully and with purpose to learn how we are all implicated and how we are all responsible to ourselves and each other, and to all creation. We have to invest time and energy in learning from the stories,” she said.

“What Indigenous Peoples need are conversations that start with a turning toward and a willingness to accept responsibility to learn from Indigenous Peoples’ experiences and perspectives,” Dion added.

Philipps, who in addition to being provost and vice-president academic at York University, is a legal scholar and professor of law. She was asked to consider the question: How do you understand your responsibility to participate in accomplishing reconciliation?

“My responsibility is to continue my own personal education and learn about Indigenous histories in Canada. My own personal education began for me as a law professor at Osgoode and my own field of scholarship and teaching, which is tax law and policy,” Philipps said. “And, about how there is a specific and interesting space carved out for First Nations and for those defined as qualifying under the Indian Act for particular types of tax treatment; the way that was expressed in case law and by judges hearing cases about that tax treatment; the kinds of assumptions and stereotypes and ideas about why that existed and what it meant.”

Philipps probed deeper into what she was seeing and began to read and research the inequities. She then brought those observations into her courses, in rather tentative ways at first, she said, and then more robustly as her knowledge increased. She attended the Anishinaabe Law Camp that Osgoode Hall Law School initiated and learned from Indigenous Elders and scholars. “What I took away from that was understanding more deeply that Indigenous communities have their own legal orders. Historically and currently, those legal orders are very much rooted in the land,” said Philipps.

She continues to pursue and deepen her knowledge through reading and conversations, listening and continuing education and brings that growing knowledge into her role as provost and vice-president academic. She is continuing to expand the numbers of Indigenous faculty at York University and is exploring how she can embed an infrastructure to support current Indigenous faculty and embed Indigenous perspectives and knowledge into the curriculum.

Hillier was the next panellist to respond. As Co-Chair of the Indigenous Council at York University, he was asked to consider the question: What have you learned from the conversations happening and/or not happening about reconciliation?

A queer Mi’kmaw scholar from the Qalipu First Nation, Hillier began with a story about his grandparents. “My grandparents never spoke of the erasure of their culture through dominant groups and violence and being ostracized, but the impacts remain. Deeply.” he said.

“I appreciate the provost’s comments around learning because this process that we are now in is not a truth-finding process, but instead it is a learning process of coming to understand and coming to terms with the truths. So, what is reconciliation? For me, reconciliation is critical to our foundation of being able to move forward as a country. Reconciliation is complex, it is multifaceted, and it is continuous and can be contentious,” said Hillier.

At its core, Hillier said, reconciliation is about learning, healing and coming together. It is about honouring the treaties that settlers entered with Indigenous Peoples. “We must acknowledge and respect Indigenous rights and titles across this country. Reconciliation is also about learning about Indigenous history.

“It means recognizing the intergenerational impacts of colonization, attempts at assimilation and the cultural genocide taking place and it means recognizing the critical roles that Indigenous Peoples have held in the creating of this country,” said Hillier. “Reconciliation is supporting the reclamation of identity, language, of culture and nationhood. I did not start my speech today with my own language because it is something that I do not have.

“When I talk to my students about the paths we are on, the journeys that we are on, I talk about a two-pronged journey. A journey of learning and a journey of healing. We all have a part in this, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, we must engage in this journey together.”

As the Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School, Condon was asked the question: What actions have you taken or want to take in service of reconciliation?

She began by saying that for legal educators and scholars, there is a strong awareness of the role that Canadian settler law and legal systems have played historically in facilitating colonial structures. “Whether that is facilitating particular types of treaty relationships and constitutional relationships between settlers and Indigenous Peoples, or the way in which settler law has facilitated the oppression that resulted in the residential school system and maintaining of those oppressive structures,” said Condon.

She observed that the comments and 94 recommendations made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission focused on law schools as being necessary to the journey toward reconciliation, including re-teaching how Canadian law has facilitated the oppression of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, creating a cohort of lawyers who can properly and respectfully serve Indigenous clients, and exploring how law schools can make space for the conversations and the study of Indigenous law.

“I think that it is fair to say that all law schools in Canada have taken up that response and that invitation from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to reflect on the role that legal education should play in the journey towards reconciliation,” said Condon.

She said Osgoode has hired four Indigenous scholars and faculty members into the school. The law school introduced an Indigenous law requirement to its JD degree and last June, the first cohort of students who have completed this requirement graduated and have a greater degree of knowledge of Indigenous perspectives on law. She is hoping to engage the law school alumni in conversations about truth and reconciliation. Condon spoke with pride about the Indigenous law camp for first year students and a law camp for upper year students. She said the law camps provide students and faculty with an opportunity to learn about communities, laws and legal orders from Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and Elders.

As manager of Indigenous Student Services on campus, Pitawanakwat, an Anishinabe with the Anishinabek Nation, is from the Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory on Manitoulin Island. He said that he was proud to be participating in the panel. He spoke about the impact of residential schools on his family, specifically his father and grandfather who attended the St. Joseph Residential School in Spanish, Ontario. “This was never spoken about to the children, it was a topic that no one discussed,” he said, noting, “the education system participated in the lack of education about Indigenous Peoples, so now the education system must now become a full participant in the reconciliation efforts.

“We need to accomplish an awareness of the past wrongs and right these wrongs. We need to accomplish a desire to join in building a new relationship. Reflecting on my current position within the York community, my hope is that we focus on establishing learning opportunities for staff and students,” he said. “There is so much to learn about Indigenous Peoples and these learning opportunities can include both in-person and online learning, including in the form of training sessions that can be made available as professional development for staff and employees. We need to build the capacity for learning and have resources available. There is a lot of work to do throughout the entire institution and we need to come together and establish a coordinated effort and set a plan, rather than the current piecemeal format.”

The learning process will be difficult, said Pitawanakwat, but necessary. “We must all work together on this, reconciliation is everyone’s responsibility.”

The last to respond in the panel, Teong brought a student perspective to the question: What actions have you taken or want to take in the service of reconciliation?

Teong responded that he felt lost and overwhelmed in trying to ascertain where to start his own journey. “As a student leader, a Canadian and the son of immigrants, my parents came to this land to build a better life. “As I reflect on reconciliation, I remind myself that impact begins with one person. I want to work in the service of reconciliation. Whether it be working with campus partners and Indigenous Student Services to learn what they do and how to incorporate their vision into our own [Glendon Student Government], I commit myself and the team to working with the Indigenous councils and student groups.”

Personally, he said that he was engaging with the Canadian Language Museum on the Glendon Campus and encouraged those viewing the panel to visit and study the museum’s free exhibit. He is pursuing his own learning through reading about the Residential School System and the intergenerational harm caused to Indigenous Peoples. He is also taking courses to learn more about the experiences of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. “As we talk about actions, it starts with learning and with difficult conversations. One person taking the first step forward and inspiring others to do the same, and it is in this spirit that we can make things better.”

In her closing remarks, Cote-Meek said that the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation represented an important milestone, and the panel was important for York University.

“As you reflect on the great injustices of the Residential School System in Canada, I want to remind you that colonization remains ongoing for Indigenous Peoples. I will leave you with the stark realities that Indigenous children and families continue to face today,” said Cote-Meek. “There are three times more First Nations children in the current child welfare system than there were at the height of the residential schools. First Nations children are six to eight times more likely to go into child welfare care than non-Indigenous children. This over-representation is largely caused by a number of factors beyond the control of individual families and parents, some of which include poverty, poor housing, under-funded education, and in many cases the lack of access to safe drinking water,” said Cote-Meek. “There are a number of other reports that are available online that I would ask you to explore. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Report remains out there and little action has been taken. A new report on the gender-diverse and non-binary community speaks to the high rates of violence directed not only to women but to that community as well.

“All of the speakers have provided us with deeper insights into what reflecting on reconciliation in action can be. There is no doubt that it will be a long journey. I leave you with this question: What will you personally commit to going forward?”

To learn more about Research & Innovation at York: follow us at @YUResearch; watch the animated video which profiles current research strengths and areas of opportunity, such as artificial intelligence and Indigenous futurities; and see the snapshot infographic, a glimpse of the year’s successes.