Workers' Stories in the COVID-19 Era: Installment #6

August 6, 2021

Written by Christina Love (Undergraduate Student, Indigenous Studies and French)

Edited by Suzanne Spiteri (PhD Candidate, Sociology)

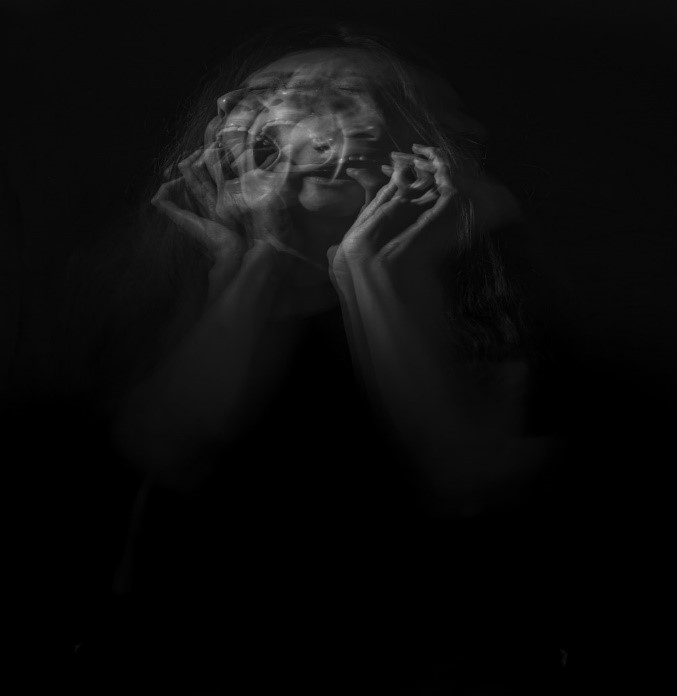

In the sixth installment of the Workers' Stories in the COVID-19 Era dialogue series, we interviewed Karl, a former veterinary assistant and current customer service representative with a hot tub retailer. In the dialogue below, we discuss the dawning realization of a worker who wants to get out of their field, and how hard doing that has become during the COVID-19 pandemic. We discover that it takes a huge toll on the mental health and wellbeing of workers.

TW: Discussion of mental health and thoughts of suicide.

For privacy, all names have been changed to protect the identities of our interviewees.

Interview

Christina: Can you describe your job, or jobs, and how long you worked at each?

Karl: I'm currently working at a hot tub retailer as a customer service representative. I've been there now three months last week. It's pretty cool. I mostly troubleshoot hot tubs and help customers.

Before that, I was working at a veterinary hospital as a veterinary assistant, and informally as a receptionist/tech. I was there for about six months. Before that, I worked at another vet clinic for about a year. Those are all the jobs that I have worked during the pandemic.

Christina: Can you describe your duties at each of the clinics?

Karl: The first one I worked at was a 24-hour clinic that handled a lot of emergencies. My job mostly consisted of assisting the technicians, handling patients, getting surgeries prepared, and doing basic cleaning.

At the second clinic, my job was more reception-based so it was booking and scheduling appointments, taking calls, and answering emails. I was still assisting with appointments and setting up surgeries and things like that, but I also did a lot of technician stuff. I took blood, I assisted with x-rays, I monitored surgeries, and I took on a lot of the administrative duties.

Christina: How has COVID-19 changed the way you work, or what has your working experience been like during the pandemic?

Karl: Pretty much every job I've worked since I was like 15 was some sort of customer relation or customer serviced-based position. And even with working at vet clinics, as much as I'd be assisting with patients, I'd also be in the room with the clients and talking with people face-to-face. So, going from seeing people on a daily basis to not seeing anybody at all and just interacting with the pets was definitely a big jump.

It took some getting used to but at the same time it was also kind of great because some people suck. It also streamlines the work, in a way, because instead of having to answer a million questions from the person in front of you, you just get the work done and then go on about your day.

Christina: Do you think that the government and your employers have done a good job adapting to the pandemic? And what supports were present or absent for you?

Karl: Until the most recent the job that I'm at now, which is outside of the veterinary field, absolutely not. Both of the vet jobs I worked at during the pandemic were very much a fend-for-yourself situation. When the pandemic first started, our hours were cut, but there was no assistance for anybody, financial or otherwise, though a lot of us worked full-time and needed to pay rent. There was an utter lack of accountability from my boss at that clinic and they basically took the stance that there was nothing they could do. That is false; they could have redistributed the profits from the business, but they chose their greed over our livelihoods.

[T]hey could have redistributed the profits from the business, but they chose their greed over our livelihoods.

At the second vet job, if you were sick at all, COVID or otherwise, you had to stay home. But if it happened too often you would get fired. For example, one of the best workers we had got fired after they and a member of their household had to take COVID tests due to risk of exposure. My co-worker was gone two weeks for that. Then they sprained their ankle at work and were fired immediately because they needed more time off. Workers have really been treated like they’re disposable during the pandemic.

Christina: How has the pandemic and working during the pandemic impacted your mental and physical health and well being?

Karl: Oh, it's definitely made it a lot worse. I would say, physically, since I’m not at the vet clinics anymore, I have less of the problems that arise when you’re restraining animals and doing that sort of thing. But during my time at the vet clinic, it was common for me to come home being physically exhausted from the labour. Mentally, it was definitely a big jump from before to during the pandemic.

Especially working in the veterinary industry, people kind of took out the pandemic on you, the worker. It was weird because I understand people are nervous, leaving their pets with you when they can’t be there. But then if anything were to go wrong, they’d immediately say it's your fault. Even if their pet had an underlying condition, which was often the reason they came in for an exam, they blamed it on you.

To have all these people cursing my name and saying that I'm killing their pet definitely took a huge toll on my mental health and made a lot of my insecurities way bigger for sure.

To have all these people cursing my name and saying that I'm killing their pet definitely took a huge toll on my mental health and made a lot of my insecurities way bigger for sure.

Christina: Can you describe your experience with job loss and job searching during the pandemic? And how does this experience compare with pre-pandemic times?

Karl: It was awful. I've worked a lot of jobs, but the process of finding a job during the pandemic was like pulling teeth with tweezers. The good thing about before was, as much as you apply on Indeed and email people your information, you could still go in and give that face-to-face connection. Honestly, nine times out of ten that's how I ended up getting jobs.

So, going from that to the point where, because of social distancing, if I was to show up in-person that would count as a point against me was such a jarring experience. For instance, when I knew I wanted to leave the last clinic I worked at, I started applying for jobs around October of 2020 and I didn't find a job until May of 2021. I applied indiscriminately to probably nine or ten places every single day. I had a dozen interviews, but the problem with the interviews is either they’re over the phone, so you lose a lot of context, or you're in-person for a single meeting. It's hard to give an amazing first impression, only once, in whatever limited form it’s taking.

Especially too, before I left the veterinary industry, being a man in that field is an anomaly. Every time I went into an interview, exacerbated because I have a unisex name[1], people would kind of take a step back because the veterinary field is 95% female. So, going into it with people also not knowing that I'm a man, walking in and making that first impression gets harder since you’re, right off the bat, not meeting their first expectation of you. It's honestly like you're running up an escalator that’s coming down. It’s brutal.

Christina: Why did you leave the job at the last veterinary clinic?

Karl: Actually, because of the pandemic, I realized that the veterinary industry is solely money-based. It’s all about extorting people and their pets for the highest possible payout. I went into it originally wanting to help, and I think most people who go into the veterinary industry go in wanting to help, which is also the reason why I was in tech school for a couple years.

I remember in my first year, our professor said that 75% of tech students will be out of the industry within five years. It's because you realize very quickly that you’re not going out of your way to help, you are going out of your way to get paid; the basic healthcare needs of pets are being treated like a luxury for people with money.

It was really hard, especially at my last job, because the owner/head vet was the only one there, and it was the first time I worked at a clinic with a single vet. It was consequently a smaller operation, so making sure we made a certain amount of money each day was super important. But we would have people coming in who had lost their jobs because of the pandemic and there was no price adjustment at all; we still had our regular exams which were around $700. Especially being a receptionist at the time, I was the one that had to tell clients to their face, “Either you pay me $1,000, or your pet dies.” It was really an eye-opening situation and I just wanted out; I was done. I like helping the animals and I liked seeing them, but I didn't like what I had to do if the client had the misfortune of being poor.

The tools set in place to help people who don't have the money to pay for services are almost nonexistent. There's the Farley Fund which takes six months to get approval for, or you surrender your pet to a rescue. But then after the surgery is done, you're legally not allowed to adopt your pet. Imagine if this happened in our healthcare system. Imagine a parent having to surrender their child(ren) to an orphanage if they couldn’t afford medical treatments, then not being allowed to adopt them back. It’s inhumane.

Imagine a parent having to surrender their child(ren) to an orphanage if they couldn’t afford medical treatments, then not being allowed to adopt them back.

Christina: If you are given ultimate power over the economy, labour rights, and the government, how would you have done things differently during the pandemic?

Karl: I think first and foremost, I would implement a universal basic income. The fact that UBI isn’t a thing is genuinely preposterous. Most of the jobs I’ve worked have barely been enough to survive on, and I’d work consistent 70-hour weeks. People who physically can't work, or are trying desperately to find a job, more and more are becoming homeless, which is crazy – we have enough homes, this isn’t a matter of housing stock, it’s a matter of capitalist greed. I think that giving people a guaranteed cost-of-living income would be the first thing to help take the edge of desperation off of the labour market, desperation that often leads to exploitation.

The fact that UBI isn’t a thing is genuinely preposterous.

I also think we should unionize everything. I don't see any real negative aspects for workers to have their work unionized. Workers are the ones who are essential, not bosses and CEOs, and unions help to lessen the exploitation they face. It's funny because in switching programs of study to social work, I'm learning a lot more about socialism and the teachings and writings of Marx. He addresses most of this and has been right since the 1800s, which is mind-blowing considering how much the world had changed since then. I guess one of the constants is proletarian oppression.

Christina: Is there anything else you want to share or any final thoughts?

Karl: I think that the main thing is that we need to find a new and effective way to job-hunt. I’ve worked a lot of jobs in my day but having to find a job during the pandemic has been one of the most difficult things I've had to do in my entire life. It was so discouraging. With employers, there is this sense of, “I can replace you at any time,” but also “I need you to be perfect because without you we’re fucked.” It's this weird imbalance of power that is exclusively taken out on the employees and job-hunters. You’re devalued, yet you’re integral.

There really needs to be a shift in how job-hunting is treated and viewed. There are organizations out there to help you, but especially if you're working somewhere already, it’s hard to access help because you’re seen as lower priority. Add in a pandemic and mass layoffs and joblessness, you’re not just lower priority, you’re ungrateful and should just stick it out and count your blessings that you even have a job. This is also an issue of underfunding too because most of these organizations don’t have the resources to help even all the people without jobs, let alone those with work trying to find different positions. Like a lot of social agencies, the sector is overburdened, underfunded, and prone to taking clients who can be used to virtue-signal.

That was the big barrier for me because I was still working full-time and trying to find a job that didn't make me actively want to commit suicide. Near the end of my time at that second veterinary clinic, suicide was an option, it was a part of my brain, and it was a way out. But because I was working full-time, if I went to places like Durham Recruiter, they pretty much told me that they couldn’t help me because I was working, even though I was always one paycheque and $50 away from starving; I could not just quit until I had something lined up. I matter just as much as everybody else; my wellbeing matters as much as everybody else’s. I should have been able to get help, but to them I wasn't broken enough.

Near the end of my time at that second veterinary clinic, suicide was an option, it was a part of my brain, and it was a way out.

In terms of government aid, I already technically made too much money to get help. And even then, I was still barely surviving, but now to add the inaccessibility of job-hunting services, it’s like they're actively trying not to help.

At the end of the day, we need more assistance, and we need more support. Finding a decent, not even good, but decent, job during this pandemic has been like trying to find a needle in a million haystacks. The system has been designed to not work for workers, for the lower classes, and it’s currently exploding around us.

[1] Changed for anonymity.