The Anti-Imperialist Geopolitical Suburb?

Caimanera as Guantánamo’s Revolutionary Frontier

Basu, R. (2022). The Anti‐Imperialist Geopolitical Suburb? Caimanera as Guantánamo’s Revolutionary Frontier. Antipode, 54(3), 681–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12807

The spatialities of anti-imperialist praxis are increasingly fraught with innumerable challenges that require complex epistemological considerations. As borderless US-based militarisation regimes proliferate globally at an unprecedented pace, embedding their political-territorial control more securely through state and logics of neo-imperial extractive capitalism, they have prevailed through the strategic discourse of “progress, security and freedom”. This paper explores the geopolitical workings of Caimanera, the town closest to the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base (GTMO), as a counter-hegemonic project to US imperialism. Referred to as the First Anti-Imperialist Trench in Cuba—a territory lying within the shadow of one of the world’s most notorious prisons and oldest military bases—Caimanera’s history is fraught with tension since the base was first established by the US in 1903. Since the triumph of the 1959 revolution, the base continues to be held against the will of the Cuban people and is strongly denounced as an illegal occupation. Based on archival material, landscape analysis, and visits to Caimanera in 2015, 2017 and 2019, this paper explores how the anti-imperialist geopolitical suburb has historically evolved through the territoriality of its governance and actions. This anti-imperialist geopolitical suburb is explored as a conceptual form and mode of praxis drawing insights from Fidel Castro’s theorisation of the “Battle of Ideas”, whereby the production of oppositional space in response to imperial threats and aggression is tackled through complexities of the city-building process and the cultural ideological resistance of its closely interwoven educational landscape. The anti-imperialist geopolitical suburb as a space of subaltern geopolitics creatively attends to the complex task of sovereignty and boldly promulgates a movement towards peace and solidarity in the larger transnational region.

Link to Critical Classroom

(Spanish) Las espacialidades de la praxis anti-imperialista son cada vez más cargadas de innumerables desafíos que requieren complejas consideraciones epistemológicas. Mientras los regímenes de militarización estadounidenses sin fronteras proliferan globalmente a un ritmo sin precedentes, incorporando su control político-territorial con mayor seguridad a través del Estado y las lógicas del capitalismo extractivo neo-imperial, han prevalecido a través del discurso estratégico del “progreso, seguridad y libertad”. Este artículo explora el funcionamiento geopolítico de Caimanera, la ciudad más cercana a la Base Naval de Guantánamo (GTMO), como un proyecto contra-hegemónico del imperialismo estadounidense. La historia de Caimanera, conocida como la Primera Trinchera Anti-imperialista de Cuba, un territorio que se encuentra a la sombra de una de las prisiones más notorias del mundo y de las bases militares más antiguas del mundo, está llena de tensiones desde que Estados Unidos estableció la base por primera vez en 1903. Desde el triunfo de la revolución de 1959, la base sigue retenida contra la voluntad del pueblo cubano y es denunciada fuertemente como una ocupación ilegal. Basado en material de archivo, análisis paisajístico y visitas a Caimanera en 2015, 2017 y 2019, este trabajo explora cómo el suburbio geopolítico anti-imperial ha evolucionado históricamente a través de la territorialidad de su gobernanza y acciones. Este suburbio geopolítico anti-imperial se explora como una forma conceptual y un modo de praxis que extrae ideas de la teorización de Fidel Castro conocida como la “batalla de ideas”, en la que la producción de espacios de oposición frente a las amenazas y agresiones imperiales se aborda a través de las complejidades del proceso de construcción de la ciudad y la resistencia cultural ideológica de su paisaje educativo estrechamente entrelazado. El suburbio geopolítico anti-imperial como espacio de geopolítica subalterna atiende creativamente a la compleja tarea de la soberanía, y promulga audazmente un movimiento hacia la paz y la solidaridad en la región transnacional más amplia.

Cuban and Soviet planes abandoned in Pearl’s Airport following U.S invasion

“Second-chance” Education: Re-defining Youth Development in Grenada

With the end of the Grenada Revolution and the subsequent American invasion, the nation’s education policies shifted from being conceptualised as a national development strategy “fashioned in our own image”, to being a project aiming to strengthen the region’s global marketplace participation through the creation of the “ideal Caribbean person/citizen/worker”. Recognising the discursive shifts in education and development, this article focuses on how Grenadian youth (16-24) interpret these institutional objectives through their participation in “second-chance” education, or non- formal education. Following Henri Lefebvre’s (1991) spatial triad, the analysis examines the concept of “second-chance” education as a socially produced space conceived by the state, perceived by organisations, and lived by the students. The article reveals gaps between discourse and practices of youth in development, highlighting ways in which youth actively navigate and respond to the socioeconomic and geographic realities involved with “second-chance” education organizations, national growth, and regional integration.

(Spanish) Con el fin de la Revolución de Granada y la subsiguiente invasión estadounidense, las políticas nacionales de la educación pasaron de ser conceptualizadas como una estrategia de desarrollo nacional “hecha a nuestra imagen”, a ser un proyecto que apunta a fortalecer la participación del mercado global de la región a través de creación de la “persona/ciudadano/trabajador caribeño ideal”. Reconociendo los cambios discursivos en la educación y el desarrollo, este artículo se centra en cómo los jóvenes granadinos (16 a 24 años) interpretan estos objetivos institucionales a través de su participación en la educación de “segunda oportunidad”, o educación no formal. Siguiendo la tríada espacial de Henri Lefebvre (1991), el análisis reconoce el concepto de educación de “segunda oportunidad” como un espacio producido socialmente, concebido por el estado, percibido por las organizaciones, y vivido por los estudiantes. El artículo revela las brechas entre el discurso y las prácticas de la juventud en el desarrollo, resaltando las formas en que la juventud navega y responde activamente a las realidades socioeconómicas y geográficas relacionadas con las organizaciones educativas de “segunda oportunidad”, el crecimiento nacional, y la integración regional.

The contrast between development discourses and practices of education in Grenada raise critical questions on what the role of education should be. Concerns surround the increasing demand for skilled workers in the face of high youth unemployment, the relevance of an academically-streamed curricula in an economy that is increasingly service-based and agricultural, and, as scholars point out, the continuing implications of systemic inequities in education that are overlooked by a narrowing focus of transitioning youth into the labour market (Bailey and Charles, 2010; Lewis, 2010). In effect, reform efforts have done very little to re-think the function of education across the region (Louisy, 2001; Jules, 2008; Hickling- Hudson, 2004; 2015). Nevertheless, the engagement of youth in the processes of learning, whether formal or non-formal, remains an area that requires further inquiry.

Against this background, I conducted a study in 2019, also the 40th anniversary of the Revolution, to investigate how these official discourses and institutional targets of “ideal Caribbean person” and education for development are interpreted and experienced by the subjects of policy— youth. My focus was on young people between the ages of 16-24 attending “second-chance” education and training organisations, or the non-formal education sector (NFE). Bearing in mind the mainstream role of education for growth and the history of Grenada’s development, this study was guided by the following questions:

- What is the meaning of “second-chance” education for youth?

- What does it mean for youth in their everyday life to be an “ideal Caribbean/ Grenadian person”?

- What are some of the challenges and opportunities youth face in their relation to “second-chance” education, regional integration, and perception of development in Grenada?

Collectively, the study highlighted education strategies and development challenges and opportunities that youth navigate, respond to, and negotiate in Grenada. Through policy-related and conceptual contributions, the study hopes to contribute to the conversation on postcolonial directions in education with youth as responsive partners, critics, and agents of change in development. The chapter sought to have youth became a part of the conversation on development rather than sole subjects of the discussion. Notably, for young persons who participated in this study, their sense of self was not merely defined by age or gender altogether (albeit impacted by these attributes), but rather by their capabilities, skills, and interests as learned and supported by “second-chance” education organisations, and how they could apply these along with their knowledge to the world around them.

Perez Gonzalez, L. (2020). “Second-chance” education : re-defining youth development in Grenada. Postcolonial Directions in Education, 9(2), 226-271. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/65661

Sources:

Bailey, B., & Charles, S. (2010). Gender differentials in Caribbean Education Systems. Commonwealth.

Hickling-Hudson, A. (2015) Caribbean schooling and the social divide – what will it take to change neo-colonial education systems?. CIES 2015 Annual Conference of the Comparative and International Education Society. Washington, U.S.A

Jules, D. (2008). Rethinking education for the Caribbean: A radical approach. Comparative Education, 44(2), 203–214.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Lewis, P. (2010). Social Policies in Grenada. Pall Mall, London: Commonwealth Secretariat. Lewis, T., & Lewis, M. V. (1985). Vocational Education in the Commonwealth Caribbean and the United States. Comparative Education, 21(2), 157–171.

Louisy, P. (2001). Globalisation and Comparative Education: A Caribbean perspective. Comparative Education, 37(4), 425–438.

Resistance and Empowerment in a Necropolis: Fighting Educational Inequality through Popular Education

Protest against Education Budget Cuts in Sao Paulo, 2019

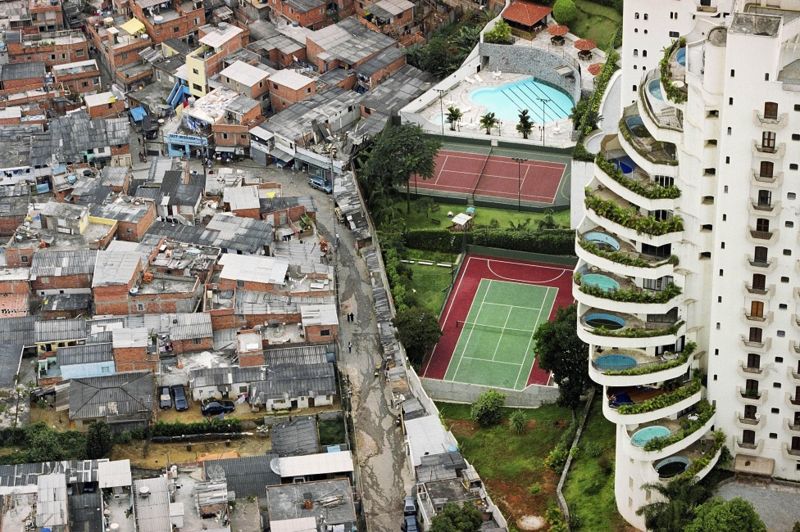

Paraisopolis Favela and Luxury Condominium in Sao Paulo

In the past two decades, education in Brazil has undergone several changes. Access to basic education is now almost universal, secondary education has been expanding very rapidly, as well as higher education, at the undergraduate and graduate levels. For the first time in Brazil’s history Afro-Brazilians are the majority in public universities, representing 50.3 percent of all students enrolled in such institutions in 2019 according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). This increase in university enrollment can be attributed to a series of affirmative action programs started by former presidents Lula Inácio da Silva and Dilma Rousseff between 2003 and 2016, one of them being the adoption of racial quotas in admission processes in Brazilian public universities (Igreja & Ferreira, 2019).

With Bolsonaro’s rise to the presidency in 2018, however, education has been primarily affected due to the adoption of neoliberal policies that have reduced funding for the Ministry of Education. An example of this is a recent approved bill that slashed a total of 2.7 billion BRL (approximately 500 million USD) from the annual education budget (The Brazilian Report, 2021). It is not an exaggeration to affirm that Bolsonaro has declared open warfare on public education, having also reduced 30% of the budget for all government-funded higher education institutions in Brazil, which include 69 federal universities and 39 federal institutions (University World News, 2019). As a result, several of these institutions have reported to be at risk of permanent closure.

While Bolsonaro has undoubtedly compromised public education, access to education in has always been an issue in Brazil, especially for Black, poor and peripheral youth. According to PNAD, despite 54% of the population self-identifying as black, Afro-Brazilians represent 75% out of the 10% poorest in the country, and this is reflected in access to education as well (Unibanco, 2015). According to the Lemann Foundation, compared to white Brazilians, Afro-Brazilians have a higher probability of either not being enrolled in school, or being enrolled in schools that have the worst infrastructure and faculty. Educational inequality is also represented in racial disparities as only 51% of black individuals are in high school compared to 65% of white students. Additionally, high school dropout rates are also an issue since among the 15 to 17-years-olds who have dropped out of elementary school 57% are black while 43% are white (Instituto Unibanco, 2015). Disparity between white and black students also become visible when looking at differences between residents of formal and informal neighborhoods. In fact, according to the IBGE’s National Household Sample Surveyamong favela residents, 70% of the population has one to eight years of schooling, whereas the same percentage of the population in formal urban areas has over five years and a significant percentage of residents has 12 years or more (Monge-Naranjo et al.). It is worth mentioning that the majority of residents who live in peripheral communities are black or pardo (mixed-race).

Racial inequality in education must be understood as a part of a process of subalternity that is reproduced in political realms of the economy and daily relations (Almeida, 2018, p. 27 in Costa et al., 2020, p. 3). This allows for an understanding of racism as a form of discrimination that is reproduced systemically, unconsciously, and consciously, and that is used as a weapon of white supremacy to cause the social exclusion and slow death of Black people. Racial hierarchization started with the exploitation and predatory pillaging of the African continent, which eventually resulted in the colonization and instilment of a race-based slavery in Brazil. This set of beliefs in the superiority versus inferiority of races was necessary to perpetuate the social exclusion that is found to this day (Santos, 2002 in Costa et al., 2020, p. 3). In Brazil, the prevalence of the myth of racial democracy and society’s unwillingness to address racism has led many Afro-Brazilians to suffer the day to day discriminations of racist oppression but not perceive it as a structural problem (Nogueira, 2013, p. 23).

However, data on inequality in education, income inequality and violence, has shown not only that Afro-Brazilians are disproportionately affected but that social exclusion is a part of a larger project of necropolitics, where the Black urban poor is prevented from exercising its right to life and to education (GIGA, 2020; Akkari, 2013). This represents a “process of invisibilization of the black youth in the Brazilian educational system with one of its main consequences being their symbolic death, which contributes to other ways of dying in the context of a society marked by structural racism” (Costa et al., 2020, p. 1). To counter such a hopeless scenario, civil society in conjunction with community members, themselves have risen up and made grassroots efforts to make higher education accessible. This has translated into free community-led programs that aim to prepare youth and adults primarily from the periphery to take Brazil’s university entrance exams. These programs are known as cursinho popular or cursinho pré-vestibular comunitário (CPVC), and while there is no official statistics on the total number of participants they have helped access higher education, current literature as well as personal accounts and experiences, have shown the importance of such programs in opening the doors to higher education.

CPVCs are examples of popular education initiatives, which provide critical education that engages students with the real world and their personal reality. Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire claims in The Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) that “there’s no such thing as neutral education” and that “education either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom.” In fact, educational spaces often reproduce dominant class value systems as well as historical and spatial processes that have led to the “stigmatization and subversions and to the demoralizing and silencing of many marginalized communities” (Basu, 2010, p. 2). On the other hand, popular education provides a space of contestation and resistance where social and cultural processes are redefined.

This project discuss and assess three cursinho populares (CPVCs) in the city of Sao Paulo – UNEafro, Cursinho Popular Professora Cursinho Popular Professora Leila Regina and Arcadas Vestibulares. Both UNEafro and Cursinho Popular Professora Leila Regina are located in Sao Paulo’s East Zone, a region characterized by low indicators of health, education, sanitation, as well as widespread poverty and criminality. Arcadas Vestibulares, on the other hand, is located at one of the University of Sao Paulo’s campuses, but also serves a population that is predominantly from low-income neighborhoods, as well as first-generation students. The research questions that frame this work are the following:

- How do popular education initiatives in Brazil perceive empowerment and what are the actual practices of empowerment and solidarity happening on the ground?

- To what extent have these initiatives empowered participants and helped them access higher education?

In the field of development, the concept of empowerment has been widely contested due to its vagueness and the difficulty in measuring it. Cornwall (2016) explains that empowerment is “one of the most elastic of international development’s many buzzwords” that can serve different agendas from radical to neoliberal ones (p. 342).

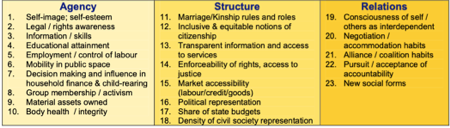

The study reveals that CPVC volunteers understand empowerment in three main ways: Empowerment as conscientization, as reclaiming identity, and as accessing spaces that have historically been denied to the marginalized – universities. CPVC volunteers’ ability to empower students is assessed using CARE’s empowerment framework, which looks at empowerment through three interrelated dimensions namely: agency, structure and relations. The analysis shows that in terms of relations, CPVC volunteers are able to collectively organize and provide community support to students in the form of resources such as food, textbooks and SIM cards for internet access. In terms of agency, it shows that volunteers can help students develop their identity and feel a sense of belonging, and that this is achieved through non-traditional classes and critical course content. However, it also shows that this is not always achieved due to the short duration of the program which limits what can be taught. In relation to structure, the assessment also identifies deficiencies that reduce the effectiveness of the programs, such as a severe lack of funding and government assistance.

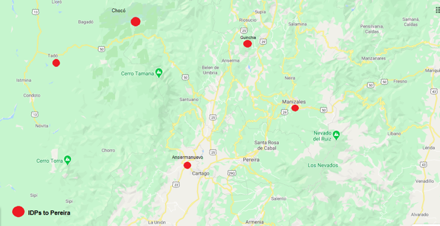

Forced Displacement and Racialization in Colombia

This thesis compares the differential processes of racialization from a Colombian perspective experienced by three groups of displaced migrants in the global North and South. First, internally displaced persons (IDPs) who have been forced to move to the Coffee Region in Colombia after leaving their homes in rural regions between 2000 and 2015. Second, Colombian refugees who had similarly sought asylum in Toronto, Canada, and who migrated between 1997 and 2004. Third, Venezuelan migrants who arrived in the Coffee Region in Colombia between 2014 and 2018 due to the deteriorating living conditions and crisis in Venezuela. This research contributes to further theoretical debates on critical geographies of race, postcolonial geography, and urban geography in relation to forced migration. The objective of this research is to question understandings of race and racism, particularly how space and mobility affect the dynamics of racialization through such diverse experiences of forced displacement. The main argument of this research is that the process of forced displacement (as experienced by the Colombian IDPs and Venezuelan migrants to the Coffee Region in Colombia, and for the Colombian refugees to Toronto), results in spatialities of racialization. While escaping violence and economic hardship, forced migrants are subjected to oppressive and exclusionary processes that make them vulnerable to systemic racism and microaggressions. This comparative research uses a combination of qualitative methodologies, including in-depth semi-structured interviews, participant observation, field diary, and policy and document reviews. The research reveals that despite different experiences of internal displacement or transnational migration, spatial processes of racialization present similar dynamics of white supremacy as the dominant racial ideology.

Map 1: Colombia and Venezuela

The maps used in this research have been taken from Google Maps and modified by the author.

Map 2: Pereira and the Coffee Region

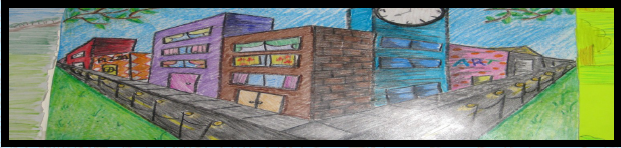

Atlas of Integrative Multiplicity in Scarborough

Overview

Atlas of Integrative Multiplicity

Scarborough is an inner-city suburb of Toronto with a population of more than 57% immi-grants of its 600,000 residents. It offers a unique perspective in understanding how the pro-cess of integration is practiced in multiple and creative ways. The rapidly changing popula-tion and historical landscape offers a unique perspective to explore how the built environ-ment has been modified and transformed into diverse uses and how the process of integra-tion moulds itself accordingly. Accessing services at places such as schools, religious institu-tions, settlement agencies, and even grocery stores, contribute to their experience of inte-gration. Integration in Scarborough, and in other cities across Canada, can be better ana-lyzed through ‘integrative multiplicity’, or in other words, how concepts of integration are imagined, understood, and practiced by newcomers through multiple public spaces within a city.

This research explores the many ways in which ‘integration’ is practiced and under-stood in Scarborough by looking at a group of diverse immigrant and refugee communities that live and work in this part of the city. Based on past research, this study seeks to under-stand the different ways that integration has evolved (or is hindered) through local institu-tions. These are articulated as

unidirectional, reciprocal or multifarious spaces of integration (Basu, 2011) where the plu-rality of cross cultural exchanges take place. It aims to contribute to a theoretical under-standing of how public spaces relate to integration and the potential implications for Scar-borough and other diverse cities that host large numbers of newcomers.

Researchers used multiple methods along with the narratives and practical wisdom of community members. Photographs were taken for a landscape analysis to better under-stand the area. GIS mapping was used to look at demographics, different public spaces, and new ways of understanding integration. Researchers reviewed a series of news articles on Scarborough to get a better take on public perception through media representation. Re-searchers then asked 49 adults and 25 youth to respond to questionnaires. Finally, four fol-low-up focus groups were carried out to explore how respondents perceive and experience public space and their integration as Scarborough residents.

The research has revealed that despite negative and stereotypical perceptions of Scarborough as a drab and dangerous city in decline, it has provided a home to recent

migrants and is understood in many different and complicated ways. Migrants under-stand Scarborough as a ‘City of Refuge and Peace’ and as a ’City of Memory, Desire and Imagination’. It is evident after some analysis that Scarborough is a ‘City of Inte-grative Multiplicity’; and has solid examples as a ’City of Civic Engagement and Fluid Resistance’.

New migrants viewed the city in this light for many reasons. They saw public space as places where diverse groups can meet, interact, and come to a broader un-derstanding of society. These types of spaces are essentially where integration is un-derstood and ‘negotiated’ by residents. The spaces are numerous and diverse, ranging from local grocery stores to public parks and libraries. They can also be found in reli-gious institutions and simply on the neighbourhood streets and can serve as one-way, reciprocal, or multifarious spaces for learning or interacting and ultimately contributing to integration.

Researchers also noted that public spaces for migrants really vary in size and scale, for example, from large scale mosques to storefront temples. They can also be both solid structures or more adhoc and unplanned spaces that change over time. Abandoned postwar industrial units, for instance, are affordable to rent as temples and mosques, educational centres, bakeries, or even floral shops. Although not always ob-vious, such spaces can especially come to life during festivals and events. Migrants use different public spaces on a daily basis and as a continuum. However, though the high cost of transit makes travelling around the city prohibitive and their daily movements very localized they maintain strong transnational links. They are able to meet and con-nect with others through family, cultural, and economic ties in these spaces that build and expand relationships and ease the settlement experience. Interestingly, cultural institutions and stores are used and even managed more and more by multiple ethnic groups which contribute to new cross-cultural alliances and multifarious spaces of inte-gration.

This research shows how different geographical contexts of inclusion and exclu-sion lead to correspondingly different experiences in understanding integration in pub-lic spaces. Cities can understand their development through the concept of ‘integrative multiplicity’ and should strive for social sustainability among immigrant and refugee communities residing in their municipalities.

Access full report here:

Basu, R. and Ko, C. (2013). Integrative Multiplicity through Suburban Realities: Exploring Diversity through Public Spaces in Scarborough. Funded by the Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Settlement. https://knaer.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/integrativemultiplicityatlas.pdf

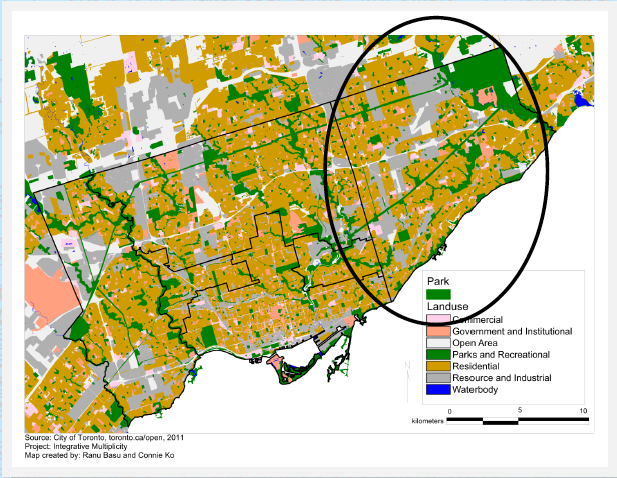

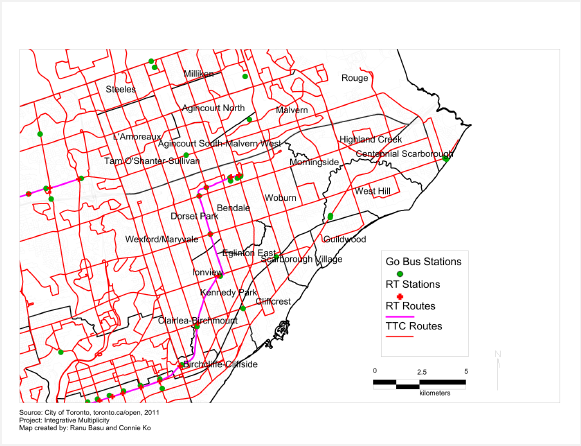

Land Use and Public Transit

Landuse in Scarborough is primarily residential. Since the post war period many abandoned industrial areas (grey parts on the map) have been converted in affordable and creative ways into cultural institutions, religious centres, small busi-nesses and even educational centres. As most of our respondents did not own cars their daily activities were restrictive and very localized. Public transit accord-ing to our respondents proved a major barrier for their movement across the city and was noted to be infrequent, inaccessible and expensive.

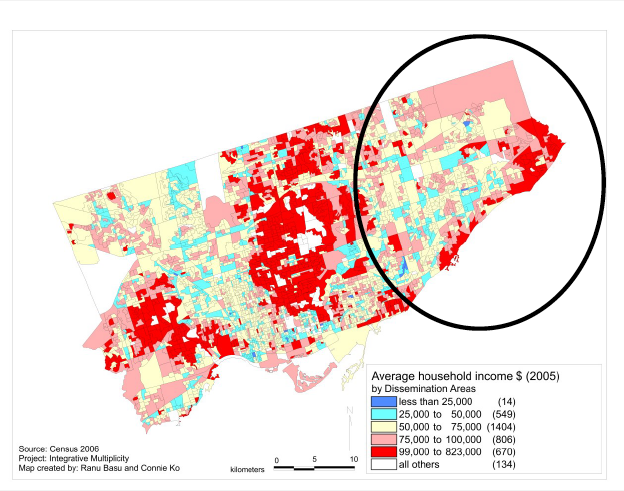

Household Income in Toronto

Scarborough and five other municipalities were amalgamated into the City of Toronto in 1998. The population also grew from 2001-2006 by 2.4% compared to 0.8% for the rest of the city (City of Toronto, 2009). In 2006, 33% of dwellings were high rise apartments and 39% were single detached homes; while 66% of dwellings were owned and 34% rented. Household income in 2005 was $53,619; and 25.8% of the population was considered to be in the low income level. According to a Social Planning forum discus-sion, 30,000 newcomer families may be among the hidden homeless in To-ronto based on newcomer and affordability statistics.

Many of our participants noted that in difficult economic times they faced the additional challenge of finding employment primarily due to: their cre-dentials not being recognized, finding affordable child care arrangements, language ‘accents’ deemed different, and indirect racism.

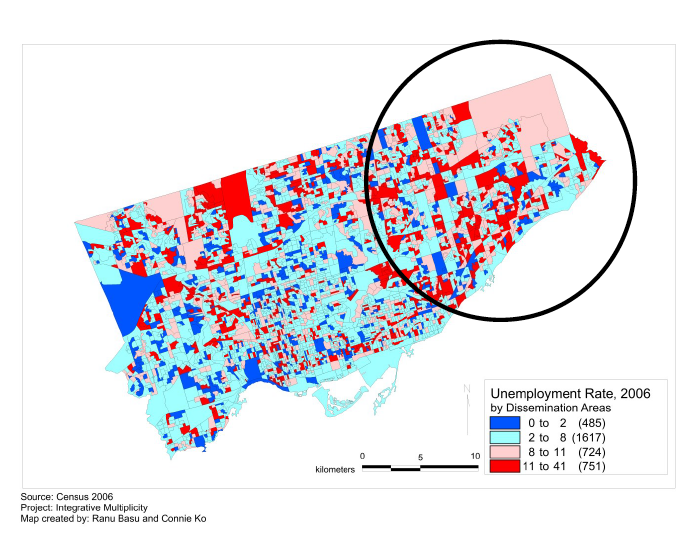

Unemployment

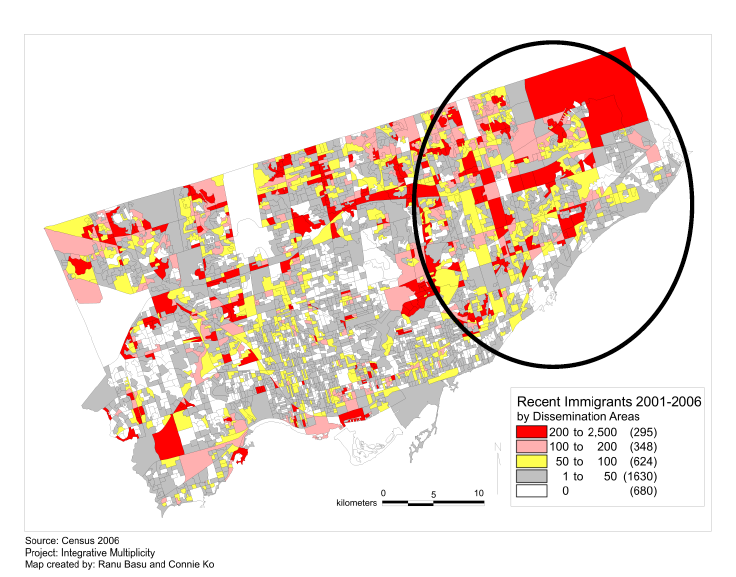

Recent Immigrants in Toronto

In 2006, 57% of the total population was immigrants, and 12% of the population was recent immigrants arriving in Canada in the past five years. Most of the im-migrants arrived from Southern Asia (36.6%), Eastern Asia (31.7%), and South East Asia (10.9%). Two thirds of the population was classified as visible minori-ties, compared to 40% for the rest of the City. The top three languages aside from English were listed in the census as Chinese (6.4%), Cantonese (6.3%) and Tamil (5.9%).

Our respondents included migrants from over twenty countries primarily from the Global South. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, China, Guyana, Hong Kong, Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Jamaica, Katoomba (Australia), Namibia Windhoek, Ukraine, (Kiyev), Israel, (Afula), USSR, Baku, Yemen, Belarus, Vietnam, and Irish/Italian, Scottish, German heritage.

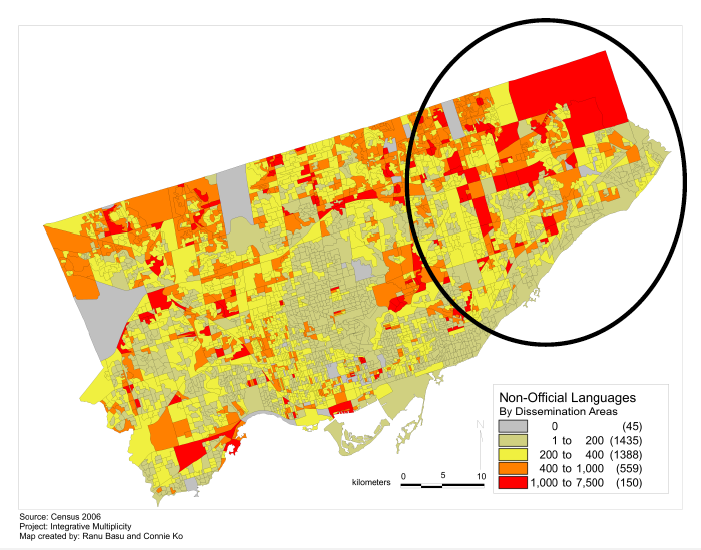

Non-Official Languages

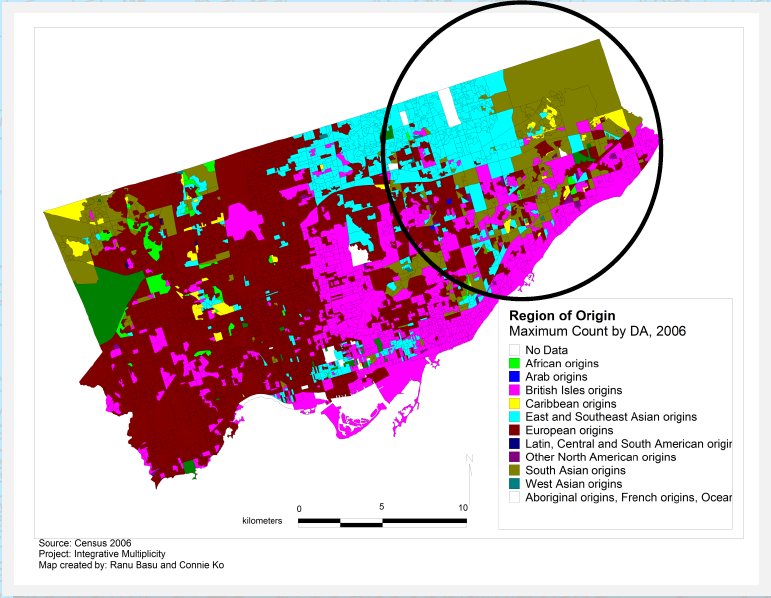

Local Diversity

Neighbourhoods across the City of Toronto are increasingly diverse at the local level. However, some neighbourhoods are dominated by specific eth-nic groups compared to others. The above map illustrates that there is a particular geography to this diversity. In Scarborough these group include South Asian, East and South East Asian, Caribbean, with a British origin pre-dominantly residing on the waterfront. Yet, most neighbourhoods contain residents from over seven countries (indicated in the opposite map by dark blue).

Critical Geographies of Education

(EU/GEOG 4700)

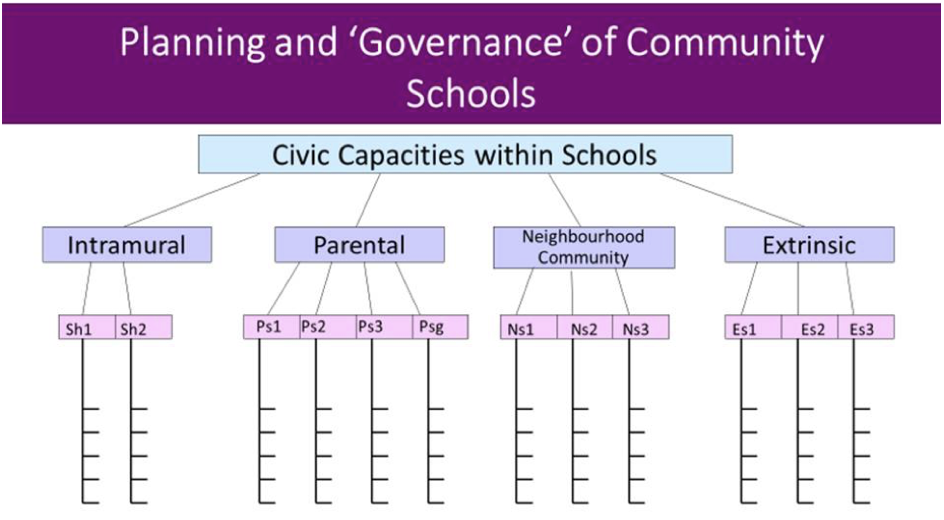

The dynamics of school-community relations are often the complex outcomes of locally based socio-spatial relations, broader political regional dynamics, and the underlying structural differences inherent within a post-industrial society. The kind of engagements that emerge as a result of this process is not necessarily confined to a school-community, but can often extend beyond the immediate neighbourhood; and thereby have impacts on the everyday rhythms and quality of life, and the political. Some of these challenges have taken on new proportions with the onslaught of the COVID-19 global pandemic and the future realm of education.

This assignment was structured to gain a collective understanding of school-community relations within the challenging context of the pandemic in the Toronto region. Through this exercise students in Critical Geographies of Education at York University (EU/GEOG 4700, Class of 2022 & 2024) gained an appreciation of the various challenges that some communities faced with respect to other schools; and the creative measures that some schools undertook to overcome these challenges. These results were presented in a series of posters and infographics geo-linked to a map of the region.

View student posters here:

Critical Geographies of Education (EU/GEOG 4700)

Source: Kudumbashree Organization

Exploring the Role of Gender Responsive Policy Making in Mitigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Women: The Case of Kudumbashree, Kerala

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected women across the world by making them more vulnerable to unpaid care work, domestic violence, and poverty. According to an analysis conducted by UN Women in 2020, 435 million women and girls would be living on less than $1.90 a day by 2021 (UN Women, 2020). Against this backdrop women centric development intervention like Kudumbashree – a women’s solidarity network and flagship poverty alleviation program of Kerala, India acquires immense significance (Shamsuddin, 2021). During the initial stages of the pandemic, Kerala’s COVID-19 response had grabbed global attention and the contribution of Kudumbashree– which was an active and critical partner in state’s COVID-19 response planning. During the pandemic many women in Kerala, particularly marginalized women, did not remain as mere beneficiaries of COVID-19 response planning. Instead, through Kudumbashree, women became active partners of these state led initiatives through taking on key challenges such as food security, provision of personal protective equipment, combating social isolation and so on. The leadership displayed by Kudumbashree women also seems to have strengthened their political presence as out of nearly 17,000 Kudumbashree women who contested local elections, more than 7000 emerged victorious (Shamsuddin, 2021). Against this backdrop this project intends to explore the role of gender responsive policy making in mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on women by tracing the journey/evolution of Kudumbashree women through this state sponsored women solidarity network and their subsequent contributions towards COVID-19 response planning.

View Todos Los Niños Del Mundo.

This past summer, GEP participated in the Canadian Association for Refugee and Forced Migration Studies (CARFM) and Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences at York University 2023. The video was recorded and presented to CARFM and CRS at Congress 2023, and played at the opening plenary of CARFM, symbolizing the importance of education for peace. Todos Los Niños Del Mundo (All the Children of the World) is a song written by Cuban singer, Tania Castellanos (1920-1988).

Born in Regla one of the humblest communities in the country, Tania Castellanos was an exceptional composer of songs dedicated to the so-called “feeling” of childhood, and to the revolutionary struggles of Cuba and Latin America. This video features children from Chorus Lucecita (little light), which belongs to the community project of the same name directed by Arnaldo Rodríguez, a well-known singer-songwriter. They develop workshops for children without academic training to bring them closer to different manifestations of art. The prestigious teacher Carmen Rosa López Hernández is the Director of the Workshops and of the Lucecita Choir, created in 2017, she also directs one of the most prestigious children’s choirs in the country called “Diminuto” created in 1993 for children who study music.

Video made by Leandro de la Rosa

Learn more about GEP at Congress 2023 in our Events page.