First published on Vasilis Molos' personal blog on January 17, 2024.

The 2019 Federal Election

By 2019, the enthusiasm that carried Justin Trudeau into power had waned. The Liberal Party of Canada (LPC) won that year's federal election but lost the popular vote by a wide margin. Bruised but resilient, they retained 157 seats in the House of Commons. Among these was Scarborough Centre, where Salma Zahid's convincing re-election left scars.

Former Member of Parliament (MP) John Cannis revisited this election in two wide-ranging interviews on March 23 and April 5, 2023, for the "Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History" project.[1] Many Greek Canadians undoubtedly recognize Cannis, a stalwart community advocate. Cannis served as Scarborough Centre's MP from 1993 to 2011 before leaving politics.[2] In 2019, he was inspired to return, motivated to address perceived problems in his riding and add a fiscally responsible voice to Parliament.

Frustrations with the LPC led him to run as an independent candidate. Along with Jody Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott, he belonged to a disgruntled group of former Liberal MPs who left—or were expelled from—the party during Justin Trudeau's first term. Cannis submitted nomination papers, anticipating support from the local Greek community. It never came.

"I was headed for victory," Cannis claimed, "but I had Greek people working behind my back." Aggrieved, candid, and prepared to show receipts, the former Parliamentary Secretary for Industry Canada recounted his memories of election day. He described how his son—a scrutineer at the polling station in his building—observed a woman whispering to her husband: "(don't vote for the Greek.)"[3] Visibly embittered, Cannis added that his daughter observed irregularities at a second polling station at the Hellenic Home for the Aged. Curtly, he surmised: "(the Greek women guided the old ladies to vote for the Muslim woman.)”[4] Some accusations were more specific. Cannis described a former friend who campaigned against him: "If she's a strong Liberal, let her campaign in her riding; why come to Scarborough Centre?" Cannis portrayed these actions as clearly "premeditated and deliberate to do me harm."[5] In his narration, personal betrayals and inadequate community support turned the election.

The Greek Community of Metropolitan Toronto Inc. (GCT) allowing all candidates to display their campaign signs outside St. John the Baptist Greek Orthodox Church was especially vexing for Cannis. Historically, GCT leadership permitted him alone to display signs outside the church. The GCT supported the Greek Canadian candidate regardless of political affiliation or ideological differences.[6] When Cannis asked for clarification about this change, he was rebuffed. He recalls then President Antonis Artemakis saying, "(we have to be objective)."[7] The community refused to favour any candidate in the riding, permitting each to display their signs. For Cannis, this shift[8] carried enormous symbolic weight. "These 2, 3 signs aren't the difference between a win and a loss," Cannis declared. "They simply send a message that the community is united."

"The Greek Canadian Community Here Has Lost the Game": The Rise and Fall of Cannis' Advocate Model of Diaspora Politics

While stories of discord may interest some, Cannis' reflections raise a more compelling question: what model of diaspora politics should Greek Canadians practice? Cannis argues that "access"—direct political participation—is essential for effective diaspora mobilization. In short, Canadian ethnocultural communities require politicians from their communities to act as advocates to access public funding and sway Canadian foreign policy in favour of their homelands. The envisioned community-advocate relationship is reciprocal and symbiotic. The community collectively endorses the advocate to speak on its behalf through gestures of public support, i.e. promoting the candidate, canvassing, and fundraising. In return, the advocate acts as a knowledgeable spokesperson and facilitator. They raise awareness among politicians and diplomats about issues affecting their community and homeland, secure funds for community projects, and influence foreign policy decisions—albeit never compromising their role as a Canadian MP or violating their Canadian Oath of Allegiance. An effective advocate maintains close ties with their community and homeland. They understand the functioning of the Canadian political system, which levers to pull, and when—and with whom—to make accommodations and alliances. Community leaders engage civil society channels in lockstep with the advocate. They coordinate "outreach" to inform the Canadian "mainstream" about issues of concern and to "let them know who we are."

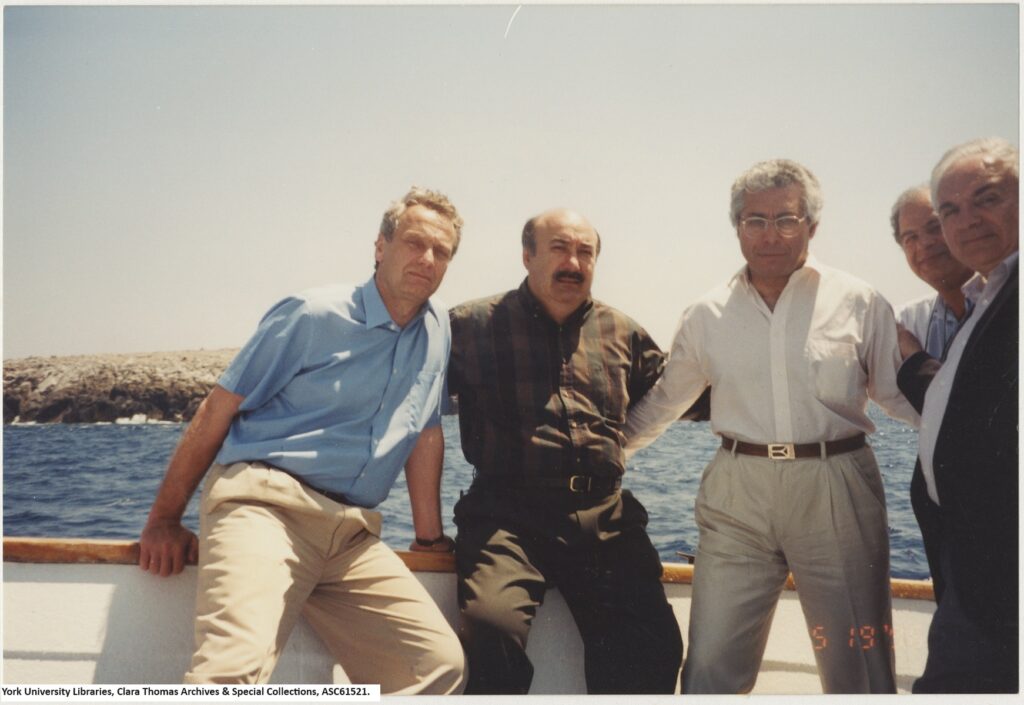

Cannis presents his tenure in office as an example of a steadfast community-advocate relationship benefiting Greek Canadians. While he was an MP, Cannis secured federal funding for the Greek Community of Toronto ($1 million), the St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church ($500,000), the "Taste of the Danforth" festival ($100,000), and the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Cathedral, to support its restoration after a fire in 2000.[9] More importantly, he served as a bulwark for Greece and Greeks. Cannis helped inform the Canadian position of neutrality on the Macedonian naming dispute in the early-to-mid 1990s. He kept his colleagues informed and accountable in 1994, insisting they refer to the then Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia by the name "approved by the United Nations and agreed upon by both parties." When the Harper government decided to recognize the country by its constitutional name in 2007, Cannis condemned the Prime Minister for "his clandestine and behind closed door decision-making style." In this notable statement, Cannis criticized the Prime Minister for what he regarded as contempt for due process and democracy. Cannis similarly took a front seat during the 1996 Imia Crisis, when Turkey claimed the two uninhabited islets of Imia. For Cannis, Canada could not stay silent, given parallels with its ongoing dispute over Hans Island: "(Canada had a) vested interest to reaffirm what the treaties had already confirmed." During a trip to Kalymnos, he chartered a boat alongside Greek colleagues to the international waters around Imia. As they approached, Cannis raised the Canadian flag to signal Canada's investment in the issue. Liberal colleague Ted McWhinney, the Minister for Vancouver Quadra, went a step further, declaring that "Greece's sovereignty and territorial title over the Dodecanese islands, including Imia, are clear and unquestioned in international law."

Alongside this advocacy, Cannis spotlights three other notable successes. In 2003, he moved motion no.318 "to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece." Seven years later, under a Conservative government, he marshalled unanimous support for his motion to reopen the Christian Orthodox Theological Institute of Halki in Türkiye. Yet, Cannis is particularly proud of his efforts to resolve the Cyprus issue. His advocacy is evident in statements denouncing the invasion on behalf of 200,000 refugees, endorsing the NATO mission in Kosovo, supporting a UN-led resolution in Iraq before the 2003 US invasion, and in debates on the Canada-Colombia Free Trade Agreement Implementation. For Cannis, normative statements are essential but insufficient to facilitate change. Education and sustained discussion are needed to galvanize support for impactful policy responses. Guided by this view, Cannis worked with Cypriot friends Dino Sofocleous and Kosti Hatzikosti to organize a large reception on Parliament Hill soon after his election. The aim was to introduce politicians and the diplomatic corps to Cypriot culture and community leaders from Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. By his account, the event's success spurred further conversation on the issue.[10]

In 1994, Cannis partnered with other MPs to establish the Canada-Cyprus Friendship Group as a venue to ensure Canada's continued engagement. The group determined that MPs had to witness life on the divided island for themselves, so Cannis helped organize a visit in 1995.[11] Eleni Bakopanos, the Minister for Saint-Denis and the first Greek-born woman elected to Parliament, participated and shared some revealing comments upon her return:

"For years I had read and spoken about the Cyprus issue. However, I could never have imagined feeling the way I did that day as I looked on to the ghost town of Famagusta, occupied by Turkish troops since the invasion of the island in 1974, more than 20 years ago. To this day there are still 1,619 missing persons, 200,000 displaced people. Religious and archaeological sites continue to be desecrated. As members of Parliament in a country that has always defended human rights, we have a duty to rise against any violation of these rights. Furthermore, Canada must make every effort to convince our southern neighbours and the international community that it is important to find a fair and viable solution to the Cyprus problem. It is my hope that I can return to Cyprus one day and see a reunited Cyprus and visit Famagusta and Kirinia, admire the view from the Pendahtila mountains and taste the fresh oranges from the orange groves of Morphou."

The following year, Bakopanos introduced a motion to promote the demilitarization of Cyprus, which Cannis supported. Sustained discussion of the Cyprus issue continued in the House for years. In 1999, Karen Redman, Member for Kitchener Centre and sitting chair of the Canada-Cyprus Friendship Group, stood to recognize the 25th anniversary of the island's division. She affirmed the importance "for all members of this House to be aware of the political problems that Cypriots face each and every day." However, the group's most significant achievement was promoting the establishment of the High Commission of Cyprus in Canada.[12] This body has bolstered diplomatic, economic, cultural, and social ties between the two countries.

Cannis' work in committees and the House was laudable, but his efforts extended beyond the Hill. He worked with the Canadian Justice for Cyprus Committee (PSEKA Canada) to engage American counterparts in conversation over the Cyprus dispute. Cannis met with Senator Ted Kennedy, Congressmen Michael Bilirakis, Bobby Rush, Porter Goss, and others to discuss recommendations for a resolution.[13] Locally, he regularly connected with Greek and Cypriot organizations. On May 16, 2002, he invited their leaders to his Scarborough office to meet Canada's Foreign Minister Bill Graham. The Presidents of the GCT, the Cypriot Community of Toronto Inc., PSEKA Canada, the Hellenic-Canadian Congress, and the Hellenic-Canadian Diaspora were in attendance. Together, they discussed the Cyprus issue, the Pontian genocide, the Macedonia naming dispute, Imia, and Halki.[14] As MP and community advocate, Cannis was a linchpin connecting the Canadian government with the Greek Canadian and Cypriot Canadian communities. He offered a voice to his community and kept the government abreast of developments in Greece and among the Greek and Cypriot communities.[15] Reflecting upon his nearly two decades in office, Cannis expresses pride over this advocacy and leadership: "(Who ran for Greece? Who ran to speak for the Pontians, the Cypriots, on Imia, on Skopje? Who brought the money to the Greek community centre of Toronto, the first million? It's thanks to John Cannis! Who brought the first half million for the community centre at St. Nicholas? John Cannis!)"[16]

Cannis' diaspora politics emerged out of frustration with a Greek Canadian community he perceived as too insular. When it came to the Cypriot occupation, "we were discussing it" in local Greek newspapers; "it just needed to go beyond that."[17] Cannis felt Greek Canadians needed better representation within Canada's putatively representative institutions. He reached his boiling point while listening to dignitaries' remarks at the Greek Independence Day parade at Toronto's City Hall in 1992: "I felt I was being patronized in the way (the politicians) were expressing themselves, what they were saying, how they were saying it." He continues, "I concluded it wasn't really from their knowledge, it really wasn't from their heart; it wasn't really because they knew what the War of Independence was in 1821." To Cannis, they appeared disinterested in the community, its history, and its priorities. This indifference was not limited to politicians in attendance; it was pervasive: "They didn't know what the Cypriot issue was all about. They didn't know where Pontus was, never mind the Pontian genocide [...] They didn't have a clue what went on in Greece." They were performing pluralism, signalling respect for diversity without any meaningful engagement: "I don't just want the city councillor or the MPP or the MP coming here once a year to tell me 'ka-li-may-ra' or 'ka-li-spay-ra' and 'Oak-see day.'"[18] The feeling that this tepid pluralism was not benefiting Greek Canadians had grown intolerable. That day, Cannis decided to seek the Liberal nomination in his riding. He won the nomination on March 7, 1993, and was elected in October.

Consistent in Cannis' narration is the sentiment that his 1993 election was a community victory. "I felt our voice needed to be heard," he exclaims. "Prior to my election, some of the issues that were important to our broader community […] were not being heard. They were not even being discussed," Cannis continues. "And I realized, as a Greek Canadian growing up, we really didn't have a voice at the decision-making table. We really didn't have an opportunity to tell our story and to bring certain facts to the table."[19] Cannis' victory enabled him to develop and execute a strategy to address these issues. His presence in the House of Commons kept Greek Canadian issues "front and centre on a continuous basis."[20] From within the government, he educated and informed colleagues through speeches, events, and committees. He formed informal platforms for Canadian and American politicians keen to support Greece and Cyprus. He established effective communication channels between Greek and Cypriot community organizations and cabinet members. Through trade missions, he liaised with Canadian businesses, banks, and universities interested in nurturing closer ties with Greece—notably TVX gold, Spar Aerospace, Turtle Island, Orlecon Technologies, Sunlike Juice Company, ice wine producers, and York University.[21] He permitted Canada to exert influence as a mediator, assisting the Canadian delegation's work with the marginalized Muslim minority in Thrace's Xanthi and Komotini regions. As Cannis sees it, he created a model for how a Greek Canadian MP can support their community and lobby for Greece as a Canadian politician. On this latter point, Cannis is clear about his cascading priorities and loyalties: "My top priority was looking after my country, the issues of Canada, the issues of my province, (and) the issues of my riding."

The Greek Canadian community rebuked Cannis' model of diaspora politics from the 2019 election. The GCT's commitment to "objectivity" was echoed by Greek Canadian MPs, who have been reluctant to serve as advocates. Commenting on this sea change, Cannis notes:

"Today, for example, we have politicians in Parliament […] who can't stand up and take positions. Somebody says to me, 'I don't want to be depicted as the Greek politician.' Who says 'the Greek politician?' You're a Canadian politician. We take on geopolitical issues. […] Then why are you talking about Ukraine; why are you talking about Kosovo; why are you talking about South America; why are you talking about China?"

From Cannis' perspective, the GCT and Greek Canadian MPs have misunderstood Canadian pluralism. Pluralism as an ethic—respect for human diversity and a commitment to balancing competing values—is one thing; pluralism as a practice—a set of institutional mechanisms governments employ to determine what projects they prioritize—is another. For him, it was misguided to expect a big-tent party—in this case, the LPC—to consistently represent a single cultural community's interests without a community representative to mobilize support. These organizations comprise diverse coalitions representing various views and interests. Moreover, Cannis believes it was self-sabotaging not to realize that large-scale community projects typically require public funding and that allocating such funds is akin to a zero-sum game among communities.

In recent years, the Tamil, Armenian, and Chinese communities have received ample funding— between $4.2 and $35.9 million—from the Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program and the Ontario Trillium Benefit to build community centres.[22] While they may take exception with this characterization, it appears that an MP or Minister of Provincial Parliament (MPP) acted as an advocate in each case: Gary Anandasangaree, MP for Scarborough Rouge Park; Aris Babikian, MPP for Scarborough-Agincourt; Shaun Chen, MP for Scarborough North, and Raymond Cho, MPP for Scarborough North. Having observed these developments, Cannis derides his community's failure to secure similar funds: "(They did not know how to access the system. They do not know what they can do and how they can use their money because it is their money.)"[23] By failing to support his campaign—and, by extension, failing to endorse an advocate—Greek Canadians effectively suppressed their voices. "Who's going to speak for us?" Cannis asked rhetorically. "I think we're losing the game," he adds, stressing his frustration has little to do with his personal defeat. The election loss was a collective failure.

Politics, for Cannis, is about compromise and concession within spaces where such negotiations yield impact. By not supporting a Greek candidate, the community shot itself in the foot before the race began. Rallying behind the incumbent Liberal MP, Salma Zahid, was a strategic failure and inconsistent with what other communities were doing: "We have to be open. Are they open? I went to the Mosque, which I helped them raise a million and a half for the Mosque we built. Do you know what they said? 'No!' They supported theirs. And you know what they did? They congregated and consolidated and got a victory." The pre-election endorsement of Salma Zahid negated the possibility of post-election access to a community advocate.

For Cannis, Greeks must support Greeks, regardless of party affiliation or—I presume—a candidate's views on issues like same-sex marriage. He points to Metropolitan Archbishop Sotirios as a community leader who unreservedly supports Greek Canadian candidates. He also notes his support for Nick Mantas and Effie Triantafilopoulos, regardless of their political affiliation. We belong to a small community of 260,000 or so. We are neither Indigenous nor do we belong to one of Canada's two founding peoples. Cannis believes our ability to contribute meaningfully to Canadian politics requires us to promote community candidates within ridings where Greek Canadians are densely concentrated—ridings like Scarborough Centre.

In making this point, Cannis did not raise the possibility that such a stance may undermine our democracy. Indeed, why would he? Diasporic people spend their lives navigating complex—and occasionally competing—obligations to their society and homeland. As Canadians, we understand our duties to other members of our shared society. Similarly, as Greeks, we feel a burden to sustain connections to our heritage, traditions, and history. Each self-identifying[24] Greek Canadian will likely interpret and weigh these obligations differently; few will deny them. Our civic commitments and ethnicity coexist; they are neither incompatible nor oppositional.

But Cannis' comments stress that our duties are situational. In his view, ethnicity must trump party affiliation and policy preferences in the pre-election contest for the Greek Canadian community to thrive. As Greek Canadians, we share enough ideas, values, and projects to unite us in coalition. Community members need not share every idea to endorse potential advocates. Community projects will not advance without this support, and Greek Canadians will lack adequate tools for swaying Canadian foreign policy. Cannis goes further, arguing that our failures since 2019 are more than a strategic misstep; they are betrayals of Hellenism: "(Today we lack a single voice in Parliament. Why? Because not only did we not support a Greek, but we openly opposed him. And these people should be ashamed. And they should have nothing to do with Hellenism because they betrayed Hellenism in every way!)."[25]

The Advocate Model's Limits

Betrayals aside, much of what Cannis has said appears sensible. I suspect most Greek Canadians agree that promoting Greek language, culture, and history in Canada is desirable. I also suspect many would want to secure Canada's staunch support for Greece's territorial integrity. Organizing and lobbying for related policies or garnering support for these ends seems reasonable and necessary. Yet, Greek Canada—like all diasporic spaces[26]—is heterogeneous and fragmented. It is a shifting constellation of varied sites with varying degrees of connection. It comprises individuals advancing diverse claims for their community and homeland. And each weighs the need for cultural promotion and homeland activism differently against others—for instance, the need to sustain national unity.

Indeed, we live in one of the most diverse democracies in the world. Nurturing the bonds that unite us as a society requires continuously affirming what we share as Canadians. Preserving Canada's national fabric compels us to make choices about who we were as a way of knowing who we are and what we aspire to be. Yet, as Will Kymlicka notes, "this link between nationhood and liberal-democracy creates endemic risks for all those who are not seen as belonging to the nation, including indigenous peoples, substate national groups and immigrants." He adds: "Since they are not seen as members of the nation or people in whose name the state governs, and may indeed be seen as potentially disloyal fifth columns, they are often not trusted to govern themselves or to share in the governing of the larger society."[27] An effective model of diaspora politics must acknowledge that cultural promotion and homeland activism do not occur within a neutral backdrop.

Then NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair reminded Cannis of this during a 2010 debate on the "Tax Conventions Implementation Act." After Mulcair expressed his "fierce opposition" to signing a trade deal with Columbia, he noted that Canada should not sign free trade agreements with parties that do not "respect our basic values such as the respect for human rights." Given that the act would not only apply to Columbia, but to Greece and Türkiye as well, Cannis rose to ask Mulcair why he had no reservations about signing a treaty with Türkiye, given that "one-third of Cyprus is illegally occupied by Turkish forces." Rather than explain why human rights abuses perpetrated by one country were more palatable, Mulcair impugned Cannis for a perceived lack of objectivity: "Unfortunately, the belligerent words he has just spoken, affirming in the House that one-third is illegally occupied, shows that he is incapable of understanding that, in these historical questions, there are always two sides to a story." After Cannis repeated his question, Mulcair went further, suggesting the impropriety of an MP engaging in homeland activism by invoking the memory of Thomas D'Arcy McGee:

"Madam Speaker, one of the more interesting lessons from Canadian history involves Thomas D'Arcy McGee, who was being pushed to take a side with the Fenians. He stood up and said that when we arrived in this country, we would assert our values and do the best that we could to share those values with the rest of the world."

Mulcair continued, asserting that Cannis was "incapable of any perspective" and portraying the Cyprus issue as practically resolved: "I am so proud to be a Canadian. I am so proud that we have used our expertise and experience on the world stage to help in a place as troubled as Cyprus. I am also very pleased, as a citizen of the world, that Cyprus now knows peace." John Cannis' reply merits an extended quote:

"I was saddened when he talked about not bringing our ways here. I too am proud of the Canadian record on peacemaking [...]. My father is a veteran of the second world war and I believe very much in what Canada has done. [...]. I was saddened when he said that. To quote him, he said he was a proud Canadian. I do not know what he was referring to, but I do not know what it is going to take. Is it going to take my grandfather, John Cannis, who arrived on these shores 105 years ago? […] Is it going to take my three grandchildren's generation before I belong […] I ask the member to reflect on the words. […] I proudly say that I am of the race of Solon. I am of the race of Pericles, Socrates, Hippocrates, Alexander the Great […], but I also am the product of Sir John A. Macdonald, Cartier, Laurier, Pearson and Trudeau. That is why I have the privilege of standing in this honourable House."

At the time of this exchange, the Cannis family's connection with Canada was over a century old, and John Cannis had devoted nearly two decades to public service. Yet, when he raised a legitimate question, the leader of a federal party questioned his objectivity and loyalty. At that moment, the limits of his advocate model came into focus.

To be clear, Cannis' model has virtues and limitations. For one, it ensures Greek Canadians have a voice in a meaningful public venue. Yet an MP's voice carries much more weight when they belong to a party with a majority in the House.[28] Moreover, this style of diaspora politics has recently fallen out of favour. Cannis' exchange with Mulcair was not an isolated incident but reflected a broader tension within Canadian culture. Since the publication of J.L. Granatstein's Who Killed Canadian History? in 1998, if not earlier, disputes among Canadian historians have spilled into the public consciousness. For Granatstein, Canadians have been contending with a "cultural challenge":

"Unthinking Canadians complacently assumed that our schools and our society had turned immigrants all into good, bland, peace-loving Canadians. But a combination of federal multiculturalism, ignorance of the values of and lack of understanding of their new homeland, and the practices of progressive education have prevented immigrants from becoming what they ought to have become: Canadians."[29]

Granatstein's stinging indictment of social history, history curricula, and multiculturalism has shaped a strand of Canadian conservative thought that increasingly pays lip service to diversity and pluralism. These arguments helped inform the Conservative Party of Canada's retreat from multiculturalism and their promotion of a "new conception of Canadian nationhood" since 2010.[30] In place of a national story about peacekeeping, Medicare, multicultural and bilingual policies, and the Charter, Conservatives have introduced a competing narrative centred on militarism and nostalgia for traditional British institutions and monarchy.[31] With challenges from the left and right, it is hard to imagine a lone advocate wielding much influence—especially if they must operate under a minority government.

This is not to say that the model is entirely unsuited to this new terrain—the success of the Tamil, Armenian, and Chinese communities suggests it retains some utility. Cannis sees The Canadian-Muslim Vote—a non-partisan organization established in 2015 to "increase civic engagement and education within the Muslim community"—as a model for creating a pipeline of Greek Canadian politicians. He argues, "The more we procrastinate in establishing such mechanisms, the more difficult it will be in the future to influence policy."[32] Certainly, civic leadership institutes could educate and empower talented youth to participate in the political process, yet diaspora politics need not be so narrowly fixated on advocates.

Beyond Advocates: Reconceptualizing Diaspora and Leveraging Civil Society

Effective diasporan advocacy and coordinated investment need not overwhelmingly depend on public funding. For instance, the Estonian and Jewish communities have relied on existing organizations and diaspora-directed capital campaigns. The $41 million KESKUS International Estonian Centre project resulted from a partnership between the Estonian House, Estonian Credit Union, Estonian Foundation of Canada, and Tartu College. The centre's funding was secured through private donations from global donors,[33] the sale of properties, and $750,000 from the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario. Similarly, the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre's $14 million renovation was primarily supported by a $5 million donation from the United Jewish Appeal (UJA) Federation of Greater Toronto and a $2.5 million donation from the centre's namesake. The renovation also received $870,000 from the City of Toronto, a portion of $15 million from the provincial government,[34] and $420,000 to cover accessibility upgrades through the Department of Canadian Heritage's Canada Cultural Spaces Fund, Ontario Trillium Fund, and the City of Toronto. In both cases, government funding supported the project but was not critical.

Coordinated investment toward community projects requires effective mobilization. UJA boasts on its website that its "annual fundraising campaign raises in excess of $60 million." By comparison, the GCT has struggled to coordinate, mobilize, and fundraise for years. Despite securing $3 million in federal and provincial funding and spending $12 million on construction, it failed to build the 80,000-square-foot Hellenic Cultural Centre. The GCT had to sell properties to service its debt. During these years, the organization appeared mired in controversy. Accusations of corruption were common, leading the GCT and its then President Costas Menegakis to launch a successful libel claim against the editor of the "First Greek Canadian Press."[35] Frictions with the Metropolitan produced another lawsuit and much public embarrassment in 2017. As tensions have eased in recent years and the GCT's $15 million debt has become more manageable, what has become clear is that the GCT's failure to build a cultural centre had less to do with corruption than with the inability to coordinate and mobilize effectively. GCT President Betty Skoutakis recently shed light on this in an interview with Bill Fatsis of GrecaTV, noting the lack of support for the centre project. In addition to the government funds, the Hellenic Heritage Foundation donated $700,000. Meanwhile, the rest of the community only raised $700,000. To quote President Skoutakis: "(There was no possibility to complete this project because the community did not respond)."[36]

Such ineffective mobilization reflects the community's generational divide, an observation made by Angelo Laskaris. The GCT and many other institutions are led by individuals who arrived in the 1960s and 1970s during the second wave of Greek migration to Canada. This generation continually expresses worry that the community will wither once they pass. In thinking diaspora, many are stuck in antiquated models that assume inevitable acculturation without Greek language learning and Orthodox Christian ritual. Accordingly, the projects they pursue and the idioms they employ reflect a preservationist logic: invest in youth language instruction and churches and recruit more GCT members to facilitate better advocacy.[37]

While many Greek Canadians share their commitments, this advocacy fails to engage most of us because it does not reflect our lived reality, particularly those of us born in Canada. An oft-cited Stuart Hall remark bears repeating: the "diaspora experience […] is defined, not by essence or purity, but by the recognition of a necessary heterogeneity and diversity; by a conception of 'identity' which lives with and through, not despite, difference; by hybridity."[38] Greek Canadians are not a monolith, nor are their politics self-evident. Many support and celebrate the Prespa agreement and Greece's efforts to integrate its western Balkan neighbours into the European Union. Many are irreligious and unmoved by calls to preserve the Patriarchal school. A significant section would not endorse a candidate who voted against the Civil Marriage Act. I would wager that only a minority is reasonably informed on Cypriot history or the Parthenon Marbles debate. And many do not care that much about Greece. As one Greek Canadian friend commented last summer: "who gives a sh*t about the Greek elections anyway?" I say this not to diminish John Cannis or the GCT but to argue that any model of diaspora politics will fail to mobilize energies if it assumes that Greek Canadians are a uniform community needing better leadership.

We are far from "urban villagers"[39] endeavouring to reproduce a static model of an idealized Greece. Each of us has a different—and typically vacillating—relationship with our Greekness. Certainly, many feel more Greek when preparing particular foods—those associated with holidays and rituals (melomakarona, vasilopita, prosfora, and koliva)—or when participating in tsougrisma, parading, or rites of passage ceremonies. Yet, Greek Canadians' cultural expression encompasses far more. Second-wave migrants may fear the loss of their community, but Greek Canadian culture is thriving. Hundreds of diverse organizations are presently active across the country. Playwrights are producing novel and transgressive cultural work, like Elisseos Kyrillou's "EΠAΓΓΕΛMA: ΠOPNH (Occupation: Prostitute)," a theatrical adaption of Lili Zografou's novel. Greek film festivals are collaborating with the Jewish Women's Club Toronto, Taste of the Middle East, and Omni Television to promote films about our shared experiences. Bands like Opa Yallah are adapting Greek music, weaving it into Arabic and Persian songs. Community leaders are contributing to a long-overdue discussion on reconciliation through the Crying Rock Initiative at Algoma University and other endeavours. Volunteers are mounting historical walking tours, creating podcasts, contributing to school curricula, and erecting historic plaques, often collaborating with city agencies, archives, school boards, politicians, and diplomats. In no way is this list exhaustive, but it is revealing of Greek Canada's vitality.

Diasporas are alive, full of syncretisms and hybridities. They draw us in, moving us to express our beliefs, contribute to our community's development, foster a sense of belonging, or influence change. They are ever "in process but persistently there."[40] Greek Canada must be interpreted accordingly. It is more than a frozen repository of idioms, rituals, and practices. Greek Canada is the reverberation of these many varied activities, the "structural effect"[41] produced through these voluntary engagements.

Any viable model of diaspora politics must recognize the diversity of Greek Canadian subjectivities expressed within this diaspora space. It must also heed Kwame Appiah's warning against aggressive efforts at cultural preservation:

"If we want to preserve a wide range of human conditions because it allows free people the best chance to make their own lives, there is no place for the enforcement of diversity by trapping people within a kind of difference they long to escape. There simply is no decent way to sustain those communities of difference that will not survive without the free allegiance of their members."[42]

A viable model will listen more than it speaks, acknowledging that the community expresses its needs, desires, and purpose within its vibrant nodes, not its dormant corners. It will promote investment in activities that animate youth—like theatre and heritage immersion programs.[43] A viable model of diaspora politics distills a symphony of voices into specific projects around which the community can mobilize, fundraise, and build.

Ultimately, any effective model of diaspora politics must leverage existing infrastructure within civil society to pursue specific goals. Greek Canadian organizations have actively lobbied governments since at least the 1980s. In 1985, the Hellenic-Canadian Federation of Ontario (HCFO) appealed to Prime Minister Mulroney to rethink the government's donation of twenty CF-104 Starfighter aircraft to Türkiye. Later that year, the HCFO wrote to the leaders of the province's three largest political parties requesting clarification on their views "regarding the policy of multiculturalism and its implementation." In both cases, the HCFO received detailed replies. Greek Canadian organizations have also lobbied as part of larger coalitions like the Canadian Ethnocultural Council (CEC). Under John Sotos' direction, the CEC campaigned against cuts to heritage language teaching in 1990.[44] Most notably, the CEC played a lead role in persuading the government to adopt the Canadian Multiculturalism Act in 1985.[45] While there is no Greek Canadian equivalent to the Hellenic American Leadership Council, sustained lobbying by various organizations on diverse issues has been the norm for decades.

In recent years, the Delphi Economic Forum has partnered with The Hellenic Initiative Canada and others to establish the Toronto Economic Forum. This national platform invites Greeks and Greek Canadians to introduce proposals to an international audience, build diverse coalitions, and develop strategies for policy development, advocacy, and lobbying.[46] A voice in the House is nice, but organizations like The Hellenic Initiative Canada, the Canada-Greece Chamber of Commerce, the Canadian Hellenic Congress, and the Hellenic-Canadian Board of Trade have a national mandate and long-standing relationships with sympathetic allies in the Canadian and Greek governments. Coordinating with and through them is essential.

Hope and the Collaborative Road

Despite Cannis' frustrations with the 2019 election, he remains optimistic. He celebrates the successes of young Greek Canadians and hopes to see the community thriving in harmony: "(I hope that relations within the Greek community as a whole find a calmness, an agreement, and understanding)."[47] I share his optimism and hopes. Since I assumed my current role, the community support for our project has heartened me. The engagement at a recent event commemorating the Athens Polytechnic uprising was particularly inspiring. Community leaders, dignitaries, and media were present. Students listened attentively to older generations recount their memories of the junta period, and all rejoiced at Chijazz's performance of anti-junta anthems. This was a special moment bereft of acrimony and full of optimism. To me, it suggested that our community has entered a new era. While past wounds may never fully heal, and generational and ideological tensions will persist, Greek Canadians appear poised to embark along a promising and collaborative road together.

Vasilis (Bill) Molos

Director and Research Lead, HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University

vmolos at yorku.ca

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Andrikopoulos, Makis. Interview. By Bill Fatsis. Talk with Bill, GrecaTV. January 10, 2024.

Greek Community of Toronto Inc. v. Gegios (Ontario Superior Court of Justice. February 17, 2006).

"John Cannis Oral History Interview Conducted by Vasilis (Bill) Molos and Angelo Laskaris in Scarborough, Ontario, March 23, 2023." From the HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History. Recording. Reference ID: GICREF015A, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/archive/john-cannis-interview-1 (accessed: January 16, 2024).

"John Cannis Oral History Interview Conducted by Vasilis (Bill) Molos and Angelo Laskaris in Scarborough, Ontario, April 5, 2023." From the HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History. Recording. Reference ID: GICREF015B, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/archive/john-cannis-interview-2 (accessed: January 16, 2024).

"John Sotos Oral History Interview Conducted by Athanasios (Sakis) Gekas in Toronto, Ontario, September 27, 2023." From the HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History. Recording. Reference ID: GICREF027, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/archive/john-sotos (accessed: January 16, 2024).

Skoutakis, Betty. Interview. By Bill Fatsis. Talk with Bill, GrecaTV. December 17, 2023.

“Ο Υπουργός Εξωτερικών του Καναδά κ. Bill Graham συναντήθηκε με στελέχη της Ελληνικής και Κυπριακής παροικίας,” Εβδομάδα: Greek Canadian Weekly Newspaper, May 17, 2002, 1 and 14.

York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, John Sotos Fonds, F0780 (Uncatalogued).

Secondary Sources

Appiah, Kwame A. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006.

Boyle, Theresa. "Ethnic Tensions Boil at Liberal Riding Vote." Toronto Star, Mar 08, 1993.

Brah, Avtar. Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. New York and London: Routledge, 1996.

Brubaker, Rogers. "The 'Diaspora' Diaspora." Ethnic and Racial Studies 28, no. 1 (1994): 1-19.

Clifford, James. "Diasporas." Cultural Anthropology 9, no. 3 (1994): 302-338.

Gans, Herbert. The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans. New York: Free Press, 1965.

Granatstein, J.L. Who Killed Canadian History? 2nd ed. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2007.

Hall, Stuart. "Cultural Identity and Diaspora." In Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, edited by Jonathan Rutherford, 222-237. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990.

Koinova, Maria. Diaspora Entrepreneurs and Contested States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Kymlicka, Will. "Solidarity in Diverse Societies." Comparative Migration Studies 3, no. 1 (2015): 1-19.

Maimona, Mashoka. "Harperist Discourse: Creating a Canadian 'Common Sense' and Shaping Ideology Through Language." MSc Dissertation., London School of Economics, 2013.

Mitchell, Timothy. "The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and their Critics." The American Political Science Review 85, no. 1(1991): 77-96.

Simpson, Jeffrey. The Friendly Dictatorship. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2001.

Tamis, Anastasios M. and Efrosini Gavaki. From Migrants to Citizens: Greek Migration in Australia and Canada. Melbourne: National Centre for Hellenic Studies and Research, La Trobe University, 2002.

Tremblay, Arjun. Diversity in Decline? The Rise of the Political Right and the Fate of Multiculturalism. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Endnotes

[1] All quotes from John Cannis are from the interview conducted on March 23, 2023, unless otherwise noted. GICREF015A.

[2] John Cannis was the first Greek Canadian to be appointed Parliamentary Secretary. He was also elected as Chairman of the Standing Committee of National Defence and Veterans Affairs and as Chairman of the trade section of the Foreign Affairs Committee on International Trade, Trade Disputes and Investments.

[3] “Μην ψηφίσεις τον Έλληνα.”

[4] “Οι Ελληνίδες βάζανε τις γριούλες να ψηφίσει (sic.) για την Μουσουλμάνα.”

[5] John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[6] The sole exception was during the 2004 election when one of Cannis’ opponents was another Greek Canadian, John Mihtis. John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[7] “Πρέπει να είμαστε αντικειμενική.” John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[8] By contrast, the Toronto Star began its story on Cannis’ 1993 nomination victory by declaring that “Scarborough’s Greek community showed up en masse yesterday and elected a Liberal candidate at a nomination battle.” Theresa Boyle, “Ethnic Tensions Boil at Liberal Riding Vote,” Toronto Star, March 8, 1993. https://ezproxy.library.yorku.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/ethnic-tensions-boil-at-liberal-riding-vote/docview/436822463/se-2 (accessed January 6, 2024).

[9] Cannis helped procure the funding for government preservationists to document the damage incurred and provide the necessary documentation for the insurance claim. John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[10] GICREF015B.

[11] GICREF015B.

[12] Andrew Jacovides was the High Commissioner of the Republic of Cyprus to Canada when the Consulate General of the Republic of Cyprus was established in Toronto in 1996. However, the first Commissioner of the Republic of Cyprus to Canada was Zenon Rossides (who was the Permanent Representative of the Republic of Cyprus to the UN and Ambassador of the Republic of Cyprus to the United States). The High Commission of the Republic of Cyprus in Ottawa was established on December 1, 2015. I thank High Commissioner Georgios Ioannides for sharing this information.

[13] GICREF015B. John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[14] “Ο Υπουργός Εξωτερικών του Καναδά,” 14.

[15] GICREF015B.

[16] “Ποίος έτρεξε για την Έλλαδα; Ποίος έτρεξε να μιλήσει για τους Πόντιους, για τους Κυπραίους, η τα Ίμια, η τα Σκόπια; Ποίος έφερε τα χρήματα στο Greek community centre του Τορόντο, το πρώτο εκατομμύριο; Είναι thanks to John Cannis! Ποίος έφερε το μισό εκατομμύριο για το community centre του Αγίου Νικολάου; Ο John Cannis!”

[17] GICREF015B.

[18] Cannis used exaggerated Anglicized pronunciations for emphasis.

[19] GICREF015B. Email to author (January 10, 2024).

[20] GICREF015B.

[21] GICREF015B. Email to author (January 10, 2024).

[22] Cannis notes that the Italian, Ukrainian, and Filipino communities have also procured government funds for community projects in recent years. John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[23] “Δεν ξέρανε πως να κάνουνε access το σύστημα. Δέν ξέρουνε τι μπορούνε και πως να μπορούνε να εκμετελλεφτούνε τα χρήματά τους, διότι είναι χρήματα τα δικά τους.”

[24] Brubaker, “The ‘Diaspora’ Diaspora,” 12-13.

[25] “Σήμερα δεν έχουμε μια φωνή στην βουλή. Γιατί; Γιατί πήγαμε όχι μονον να υποστηρίξουμε έναν Έλληνα, αλλά πήγαμε στα ανοιχτά και εναντίον του. Και αυτοί οι άνθρωποι πρέπει να ντρέπονται και πρέπει να έχουν τίποτα να κάνουν με τον Ελληνισμό διότι προδώσανε τον Ελληνισμό από όλες τις απόψεις!”

[26] Brah, Cartographies of Diaspora, 208.

[27] Kymlicka, “Solidarity in Diverse Societies,” 5.

[28] Simpson, The Friendly Dictatorship.

[29] Granatstein, Who Killed Canadian History? 2nd ed., 17.

[30] Tremblay, Diversity in Decline?, 107-117.

[31] Maimona, “Harperist Discourse.”

[32] John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[33] Nearly $18 million as of November 2023.

[34] These funds were designated to upgrade three Jewish community centres. They were a product of the UJA’s Tomorrow Campaign.

[35] Greek Community of Toronto Inc. v. Gegios (Ontario Superior Court of Justice. February 17, 2006).

[36] “Δεν υπήρχε περίπτωση να γίνει αυτό το έργο γιατί δεν ανταποκρίθηκε η παροικία.” Skoutakis, Betty. Interview by Bill Fatsis. Talk with Bill, GrecaTV. December 17, 2023.

[37] Skoutakis, Betty. Interview by Bill Fatsis. Talk with Bill, GrecaTV. December 17, 2023.

[38] Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” 235, italics in original.

[39] Tamis and Gavaki, From Migrants to Citizens, 124. Gans, The Urban Villagers.

[40] Clifford, “Diasporas,” 320.

[41] Mitchell, “The Limits of the State,” 94.

[42] Appiah, Cosmopolitanism, 105

[43] Andrikopoulos, Makis. Interview by Bill Fatsis. Talk with Bill, GrecaTV. January 10, 2024.

[44] York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections, John Sotos Fonds, F0780 (Uncatalogued).

[45] GICREF027.

[46] As articulated on its website, its aim is “to foster new opportunities for further economic cooperation, highlight investment opportunities in both Canada and Greece and deepen the ties between the business & political elites as well as civil societies of the two countries.”

[47] “Εύχομαι οι σχέσεις της Ελληνικής παροικίας as a whole να βρούνε μια ηρεμία, μια συνεννόηση, μια κατανοήση.”