First published on Vasilis Molos' personal blog on March 20, 2024.

"Sunny Ways"

"Sferazza—bit of a hard name to pronounce," remarked comedian Sam Sferrazza, adding, "I refuse to change it for show business." Having built the audience's anticipation, the comedian delivered his punch line: "This country got real warm and cozy with Stroumboulopoulos." A typical quip about a Greek name—"Who is George Snuffleupagus?" anyone?—the joke landed. As the laughter subsided, Sferrazza muttered, "Sound it out; you'll figure it out."

The joke hit its mark. The sentiment that Canadians can learn Sferrazza because they correctly pronounce the vowel-laden, 17-letter Stroumboulopoulos was relatable. Nothing in it was mean-spirited. Indeed, Sferrazza's joke would not incite raucous laughter if the audience perceived it as hateful. We would never laugh at someone for having a foreign-sounding name. Such gestures are retrograde. Worse, they are anti-Canadian.

Humour often lies in subtext, though. In this case, the joke hinged on a story liberal Canadians frequently share: the forces of History have produced a diverse, inclusive, and tolerant society in Canada. Less pompously translated: Canada welcomes newcomers. We often remark that Canada opts for "sunny ways" when minority rights are endangered. Each Tupper and Harper will inevitably arouse a Laurier or a Trudeau to mend fences, "appeal to the better angels of our nature," and inspire "peace among all creeds and races."

This powerful social myth is punctuated with anecdotes about peacekeeping, multiculturalism, and marriage equality. Similarly, it is informed by the sentiment that the legacies of structural racism and settler colonialism will be unsettled by adding Viola Desmond, Mary Simon, and others to the pantheon of Canadian heroes. The arc of the moral universe is long, liberals claim, but it bends towards inclusion and social justice. A mix of Whiggishness, Canadian politesse, and a healthy dose of anti-Americanism lead many to reaffirm this superficial understanding of our past.

George Stroumboulopoulos' icon status only bolsters this case. It is hard to deny that seeing someone with a national platform and a name "like mine" or who looks "like me" is validating. Most regard such examples as testaments to successful integration. Representation has become the touchstone of our progress. The sentiment is equal parts beautiful and naive.

The Long Road to Warm and Cozy

After Sferrazza posted his joke to social media, he challenged Stroumboulopoulos to reply within 24 hours. Strombo accommodated. Settled in his '71 El Camino, he replied in his typically effortless charismatic manner. As Nana Mouskouri's music flowed softly in a choreographed display of muted Greekness, Stroumboulopoulos recounted an early career experience. He described the awkwardness that preceded his first shift at a Kelowna radio station when a senior employee pressured him to adopt a radio name: "That ethnic thing may fly in Toronto, but it's not going to work out here with us!" Soon, the time came for George to be introduced. Rather than stir the pot by wrestling with his pentasyllabic surname, another DJ dubbed him the "G-man." Stroumboulopoulos hosted the metal show for a few months before returning home to join the Fan 590. He left the "G-man" moniker in Kelowna.

The moral of the story is that people were not always warm and cozy with Stroumboulopoulos. As his profile grew, the public slowly learned his name. This acceptance developed in a supportive climate and owed largely to George's steadfast fidelity to his "big, beautiful name."

In our eagerness to celebrate ethnic minorities' increasing representation in public life, we often overlook the assimilationist pressures they have faced. The pages of mid-century Toronto phonebooks listing truncated Greek surnames offer one reminder. Stroumboulopoulos' reply also reminds us that this erasure occurred within living memory. He described how older Greek men would approach him on the street to express their pride in seeing his long, unaltered Greek name displayed proudly on TV sets nationwide.

For George, the coercive anglicization he and others experienced was common: "If you grow up in poor immigrant neighbourhoods, you're used to Anglos not really getting the majesty of your culture." True. However, Greek immigrants across the socioeconomic ladder experienced these pressures. In a recent oral history interview, a lawyer described how he changed his name after repeated goading by one specific judge.[i] We forget this history at our peril.

Competing Unity Visions

The ethnic subject and the comedian exhibit certain similarities. In their unique roles, they serve as mirrors to society, reflecting its nuances and absurdities. They stand at the crossroads of belonging and observation—present, never fully integrated, and always yielding unique insights. The Sferrazza-Stroumboulopoulos exchange revealed how far Canada has come and how difficult the road was.

Yet, these victories are tenuous. Large swathes of our country cling to a different self-image rooted in a divergent interpretation of history. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper has been among its most influential proponents. In his obituary of Pierre Trudeau, Harper opined on the elder Trudeau's national vision before railing against him for lacing "so many federal policies [...] with the special claims of identity politics." By Harper's accounting, the supposed champion of unity produced the opposite: "regionalism, globalization, (and) Quebec particularism." Where liberal Canadians maintain that bilingualism and multiculturalism foster inclusion and integration, Harper and others disagree. In their view, these policies encourage fragmentation and disharmony.

Harper's disappointment with the "bastardized" version of Trudeau's "unity vision" informed his politics considerably. He regarded critical parts of Pierre Trudeau's legacy (the Charter, official bilingualism, and multiculturalism) as "the myths that guide the Canadian psyche." This frustration generated a new vision that centred Canada's military history and British heritage. Harper's unity vision was expressed in a "politically charged heritage policy" that excluded various minority communities' histories and drew the Canadian Historical Association's ire.

These efforts to recast Canadian identity took definitive shape in Harper's last months as Prime Minister. Many undoubtedly recall references to "old-stock Canadians" and "bogus refugee claimants." Yet, this was one of several statements affirming the "real" nationalism[ii] his party promoted as a "small-c conservative alternative to the established Liberal narrative about Canada." Inclusive of Quebec federalists, it made little room for cultural pluralism and seemed fixated on excluding Muslim Canadians. When the Prime Minister protested against Zunera Ishaq's refusal to remove her niqab when taking her citizenship oath, declaring, "It is not how we do things here," Canadians heard the dog whistle loud and clear.

The Harper era offered a decade-long reminder of Canadian culture's strong assimilationist current. It underlined that representation—where it exists—was not easily achieved or guaranteed. Sunny days are great, but the north wind does not stop blowing because a traveller removes their cloak.

"What Goes Around Came Around"

The "Greeks in Canada" research project has revealed that assimilationist and exclusionary pressures are common experiences for Greek Canadians. These pressures come in many forms beyond name changes. Some participants recount memories of bullying and physical violence in youth.[iii] Others recall homophobic comments they encountered when wearing the fustanella on public transit. For many, the foods they ate at lunch were powerful markers of difference. Spanakopita, rutabaga (gouli), and tongue sandwiches provoked revulsion, disgust, and mockery.[iv] One colleague's mother remarked on the irony: "They mocked me for eating Greek yogurt, and now everyone's eating it!" Some experiences were unique. One third-wave immigrant was interrogated about how they celebrate Canada Day by an acquaintance.

Despite these variations, most Greek Canadian accounts stress the same desire former Member of Parliament John Cannis once voiced to Prime Minister Jean Chretien:

"When our grandparents and parents came to this beautiful country called Canada, a country that we now call home, they came to build together, and today, all we ask is that we share it together."[v]

Above all, Greek Canadians seek fair terms of integration—the right to practice our culture and share in Canada's prosperity freely.

Despite unpleasant experiences, this yearning has not led Greek Canadians to behave wholly benevolently. Many reproduce the assimilative demands they once faced. By centring stories of coercive anglicization and victimization, we frequently overlook how Greek Canadians mistreat one another. For instance, one interviewee explained how her family concealed their Vlach identity in Canada, owing to the disparaging ways Greek Canadians describe Vlachs.[vi] Pontian Greeks and Cypriot Greeks,[vii] too, recount similar experiences of discrimination. These patterns also emerge in our communal associations. Most glaringly, the Greek Community of Toronto Inc. continues its exclusion of non-Orthodox Greeks (including Old Calendarists).[viii]

We often enforce hierarchies of Greekness imported from Greece and, in some cases, inscribe them into hierarchies of whiteness discovered in Canada. The association of Pontian Greeks with Newfoundlanders offers one example. Like many white ethnics, Greek Canadians' experiences as both victims and perpetrators of coercive anglicization spawn fascinating contradictions. One interviewee described how she was scolded as a little girl by her neighbour: "Don't you ever talk Greek in front of somebody else!"[ix] The neighbour assumed the girl had been talking to her father about her and was offended by this concealment. She felt entitled to complete transparency from the minority, as Harper had with Zunera Ishaq. Divergences from a normative whiteness often elicit immediate demands for visibility—frequently deemed more important than free cultural expression and religious freedom. After the interviewee explained how terrible the experience made her feel, she described a similar encounter years later: "I went to a hairdresser, and they were talking a different language [...], and I said to them, 'don't do that [...] because your customer will think you're talking about them!' She, too, appreciated the irony: "What goes around came around."

Narrating Greek Canadian history in terms of struggle and inevitable integration is reductive. Our history contains more texture. Certainly, our increased visibility on screens, in boardrooms, and on the Supreme Court merits promotion, particularly when contextualized as the product of collective effort, individual perseverance, and environment[x]. However, celebrating these successes can produce self-congratulatory caricatures of Greek Canadians as "model ethnics."[xi] Affirming this self-image silences uncomfortable pasts. It often leads toward a self-fashioning of Greek Canadians as "good immigrants" adhering to Western values—"individualism, discipline, [...] work ethic, order and equality."[xii] What is worse, the "good immigrant" requires their constituting other, a foil against which their identity becomes legible. In propagating anxieties around new arrivals, many Greek Canadians reproduce ingrained racial hierarchies. Experiencing assimilationist pressure, it seems, does not preclude internalizing the logic of assimilation.

Harnessing Empathy, Marshaling Agency

A couple of weeks after the Sferrazza-Stroumboulopoulos exchange, a Pickering city councillor came under fire for a column she penned in the Oshawa/Durham Central newspaper. Questioning the need for Black History Month, Lisa Robinson asked, "Why are we celebrating 'black history month' in Canada? Pickering's mayor quickly denounced the piece as "racist, irresponsible and unethical." At a follow-up council meeting, fifteen community members expressed similar concerns. Robinson remained silent. In a Facebook reply, she dismissed the criticism, claiming the mayor "seemed to exploit members of the black community, many of whom directly benefit from the Mayor of the City of Pickering through funding." She professed her commitment to fairness, "the principle of unity and equality," and added a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. for good measure. In this case, the irony was completely lost on her.

When such issues invariably arise, white/white-passing ethnocultural[xiii] communities are well-placed to contribute. For one, we recognize erasure and micro-aggressions. Many can relate to not seeing our histories discussed in Canadian classrooms. We appreciate the absurdity of portraying history pedagogy as neutral before school boards introduced Black history modules.

Yet, we must not overstate the similarities. Greek Canadians' proximity to—and, for many, identification with—whiteness produces differences in lived experience. Greek Canadians are not disproportionately affected by policing activities, nor are they subject to systemic discrimination within the criminal justice system.

Our history affords us unique insights and kindles an empathy we must harness; our lived racial experience affords us agency we must marshal. Today, Greek Canadians can laugh with Sam Sferrazza and celebrate George Stroumboulopoulos. We recognize that the "ethnic thing may fly" now, after hard-fought battles and with sustained support. Moreover, our history is taught along Black Canadian history as Canadian history, and rightfully so. When attacks on inclusive education are voiced, we must defend the inclusion of vital perspectives previously overlooked. History curricula should reflect each community's contributions to our country and nurture connection and civic solidarity.

As Canadians, we are all stakeholders in this shared project. Each of us belongs and "might belong in a very different way."[xiv] We are Pierre Trudeau's legacy. Our bonds grow stronger as we build community around "human values: compassion, love, and understanding." Our successes reiterate that "uniformity is neither desirable nor possible in a country the size of Canada."[xv]

The terms of debate have evolved since the passage of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act.[xvi] Still, the challenge remains the same: integrate all Canadians into our society on fair terms and sustain our ever-tenuous harmony. Assimilatory and exclusionary currents will always resurface and acclimate to new discussions. Reasonable people may disagree on issues, but Greek Canadians' agency must remain rooted in empathy. We must remember the thorny road our families toiled. Our integration experience and incorporation into whiteness—while incomplete and contested by many—came with a warning: beware the subdued elements of white nationalism behind euphemisms like "unity" and "neutrality." Heeding this caution, we must continue to navigate spaces where our voices may more readily influence change with compassion, love, and understanding.

Or, perhaps, I read too much into a joke that was only kind of funny. Sorry, Sam.

Vasilis (Bill) Molos

Director and Research Lead, HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University

vmolos at yorku.ca

Endnotes:

[i] Karas, James. Interview by Athanasios (Sakis) Gekas and Alexandros Balasis. 14 February 2024. GICREF017, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History, The HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[ii] Alternatively, “renewed patriotism.”

[iii] Cannis, John. Interview by Vasilis (Bill) Molos and Angelo Laskaris. 3 March 2023. GICREF015A, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History, The HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[iv] Tambakis, Chris. Interview by Vasilis (Bill) Molos and Theo Xenophontos. 8 March 2023. GICREF014, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History, The HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[v] John Cannis, e-mail message to Vasilis Molos, January 10, 2024.

[vi] Papademetriou, Maria. Interview by Effrosyni Rantou. 29 May 2023. GICREF029, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History, The HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[vii] Partheniou Grasso, Stella. Interview by Theo Xenophontos. 30 June 2023. FAMREF010, Film as Mediator: Cultivating a Cypriot Canadian Community Audiovisual Media Archive, The HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[viii] See also GICREF017.

[ix] Lakas, Koula. Interview by Athanasios (Sakis) Gekas and Angelo Laskaris. 24 January 2023. GICREF001A, Greeks in Canada: A Digital Public History, The HHF Greek Canadian Archives at York University Digital Portal, https://hhfgca-archive.webflow.io/. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[x] Specifically, multiculturalism policy and pockets of unparalleled diversity.

[xi] Yiorgos Anagnostou, Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009), 127.

[xii] Anagnostou, 84-85.

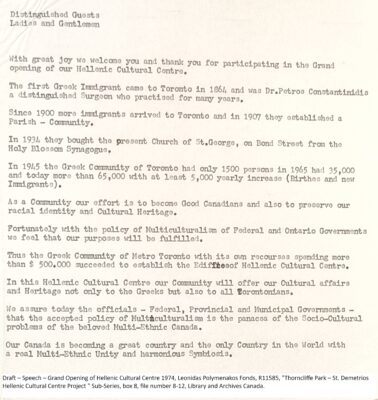

[xiii] It is interesting to note that Dr. Leonidas Polymenakos, who served as President of the Greek Community of Toronto Inc. from 1971-1982, often described Greek Canadians in racial terms. Consider the following passage from a public speech delivered at the opening of the St. Demetrios Hellenic Cultural Centre in 1974: “As a Community, our effort is to become Good Canadians and also to preserve our racial identity and Cultural Heritage. Fortunately with the policy of Multiculturalism of Federal and Ontario Governments we feel that our purposes will be fulfilled.” Draft – Speech – Grand Opening of Hellenic Cultural Centre 1974, Leonidas Polymenakos Fonds, R11585, "Thorncliffe Park – St. Demetrios Hellenic Cultural Centre Project " Sub-Series, box 8, file number 8-12, Library and Archives Canada.

[xiv] Charles Taylor, "Shared and Divergent Values" (1991) in Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism, ed. Guy LaForest (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 1993), p. 183.

[xv] Pierre Elliott Trudeau, as cited in The Essential Trudeau, ed. Ron Graham (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1998), pp.16–20.

[xvi] Perspectives on how to preserve minorities’ political and cultural rights while maintaining national unity have evolved since Meech Lake and Charlottetown, particularly after The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, during the niqab debate, and as part of “Wexit” discussions.