PROGRAM ACTIVITIES

The Robarts Centre Fellows program is currently on hiatus.

The Robarts Centre Fellows (RCF) program was launched in the fall of 2018. RCFs will build their skills and knowledge through a year-long series of events and collective activities. They will benefit from a peer network of support and access to a wide range of opportunities. Through attending a minimum number of Robarts events, volunteering commitments and mentoring sessions, RCFs will have a chance to complement their academic learning experiences by deepening their understanding of the common patterns that are emerging on Canadian topics, beyond the classroom.

In 2022 the Fellows organized the first Robarts Centre Fellows Symposium titled “Whose voices do you hear? (Re)defining the Margins of Solidarity in Canada." (Click here for details.)

Cohort Year

Read about the experiences of our Fellows below!

This June, I am graduating from York University with a Criminology Degree and a Certificate in Black Canadian studies. Completing my degree during a global pandemic has been a unique experience - I did not expect to be writing research papers from my childhood bedroom or attending lectures on Zoom from my kitchen table. I have spent the past few weeks of my time left as an undergraduate reflecting on the past four years I spent at York and home and how this time has shaped me as an individual and allowed room for me to grow.

I started my university career with different expectations in mind or rather no expectations. All I knew was that I wanted to create an impact wherever I found myself. I struggled for a very long time to discover what my passion is, and that struggle continues even today. After endless hours of internal struggle and worry about what my future could look like I finally decided to not worry about what lies ahead, but rather live in the moment and get involved in as many things as possible both on and off-campus. This decision to “seize the day” was an unconscious quest to discover who I am, and what my passions are, and the picture has slowly started becoming clearer.

In my quest for self-discovery, I was introduced to the Robarts Centre for Canadian studies and later became a Robarts Centre undergraduate Fellow. As a fellow, I was given the opportunity to attend various panels, conferences and discussions hosted by the different schools with topics ranging from post-grad pathways (Academia vs Professional) to Canadian heritage. The Robarts Centre Fellows for our year-end project were given the privilege to plan and host the 2021-2022 Robarts Centre Fellows Symposium that took place virtually on May 6th and 7th 2022 with the title “Whose Voices Do You Hear? (Re)Defining the Margins of Solidarity in Canada.”

The process of planning for this symposium was filled with challenges from choosing the date and time to navigating proper communication between the fellows regarding our vision for the symposium. The collective effort of everyone at every stage of the planning process taught me the value of clear goals, perseverance, and right guidance in any task one decides to undertake. Planning an academic symposium was completely new territory for me and although there were times when I was frustrated, upset, confused, and panicked I was able to use this medium to improve and utilize skills that I have acquired in my university career such as interpersonal skills, problem-solving and conflict resolution. The planning team was very intentional about giving opportunities and creating a safe space where different voices can be heard, and the conversation of equity could be balanced to a certain level.

My panel was called Activism and the arts, and I was determined to have a balanced conversation where activists, artists, academics, and those who are both activists and artists can share their thoughts without fear of critique. Art is a multi-dimensional form of storytelling that helps us understand the past, recognize the present and envision a better future and this concept anchored the questions that I asked and the conversations my panelist had. The diversity of modern art (music, film, paint etc) or display of art especially with the alternative perspective that social media offers can create an environment of performative activism. Performative activism is activism done to increase one's social capital rather than because of one's devotion to a cause. It is often associated with surface-level activism, referred to as slacktivism. The term gained an increased usage on social media in the wake of the George Floyd protests.

Finally, the support and motivation from Robarts Centre faculty and the staff were vital to the success of the symposium. I got involved with the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies with the desire to broaden my knowledge of the country I call home and I have truly enjoyed studying alongside classmates with goals and perspectives that differ from mine. I have learned a tremendous amount from my peers who are working towards careers in different fields which embodies the true spirit of what the Robarts Centre undergraduate fellowship entails.

It has been my absolute pleasure to serve as a Robarts Centre Fellow during the 2021-2022 academic year. The end of this fellowship not only marks the end of this occasion but my journey as an undergraduate student at York University - Glendon College. When I first started university I was only in International Studies, but I am finishing my degree with an iBA, Trilingual, Honours with a double major in International Studies and Canadian Studies, something I could not have dreamed of four years ago. I stumbled upon Canadian Studies by chance. When I was in second year, I found the one course where International Studies and Canadian Studies intersected and fell in love with the Canadian Studies program. In that course I met a previous Robarts Centre Fellow who encouraged me to take more Canadian Studies courses. At the beginning of my fourth year when I saw advertisements to become a Robarts Centre Fellow I was intrigued, a program that let me pursue my interests and gain a network of mentors and like-minded peers, sign me up.

There were two main highlights of my fellowship. The first was the many panels, conferences and Q&A sessions I was able to attend. Being a fellow meant I was forwarded an array of events to attend, and every one I was available for I went to. I attended a Q&A session on the Arctic, something I am extremely passionate about and even attended lectures on topics I knew nothing about, such as just renewable energy transitions and the climate emergency. These panels helped me grow intellectually and taught me how research can be used after your degree has ended and inspired me to pursue my academic career even further.

The second highlight of my fellowship was creating a symposium with the other Robarts Centre Fellows. Creating the symposium was a lot of hard work and dedication, the symposium entitled ‘Whose voices do you hear? (Re)defining the Margins of Solidarity in Canada’ gave me knowledge on how to set up and manage events, work with others and even gave me confidence on speaking with people I did not know and the opportunity to gain confidence when asking people to work with me. Being a Robarts Centre Fellow during the pandemic and having to create our symposium online definitely posed some challenges, but I was still able to make meaningful connections with everyone involved and looking back I would not change a thing. However, with the guidance from Jean Michel Montsion we gained invaluable experience on how to be hosts, I know I will take everything I have learned and apply it in my future endeavours.

The panel I hosted on Indigenous Language Activism and Advocacy was extremely important to me. I had pitched this idea in the fall when we first discussed panel ideas and I was so happy that everyone agreed to it. The panel had two Indigenous allies and two Indigenous people one who is Lenape and the other who is Anishinaabe. In this panel we discussed important questions such as; What does language reclamation look like for your community or communities you’ve worked with?, Why is language reclamation important?, How can people educate themselves on Indigenous language learning? And What do you hope the future of Indigenous language learning looks like?. The panel brought to light that although recently there has been a reclamation in Indigenous Language learning more needs to be done. More people need to actively seek to learn Indigenous Languages and there needs to be more concrete policies in place that put Indigenous language to the forefront, promote them across Canada and give them the credibility that they deserve. The panel was a great success because of all of the wonderful panelists, our moderator from Able York and from the help of the other Robarts Centre Fellows.

I want to thank not only the other Robarts Centre Fellows, but also Alex Felipe and Laura Taman, the wonderful team at the Robarts Centre who helped us all along the way. I also want to thank all of the panelists and participants who attended our symposium because without them our vision would not have come true. Finally, I want to thank Able York for graciously helping us set guidelines for our event and helping me lead my panel.

Participating as a Robarts Centre Fellow was an incredible experience during my third year at York University. I signed up mostly unknowing of what to expect, as I had only a slight interest in Canadian studies as a whole. The Fellowship, though, allowed super broad conversations about literally anything connected to Canada, such as history, climate change, the environment, politics, social justice, and much more. I was nervous about the unexpected responsibilities, but once thrown in, everything, such as organising or hosting panels, was manageable among the support from the Robarts Centre and other Robarts Fellows of this year.

Hearing about the opportunity for Fellowship is actually a small butterfly effect. As stated, I am a student at York — specifically a commuter to the Keele campus — and I major in Social Work. Now I had no intent of ever taking anything related to Canadian studies, maybe one odd history class, but nothing to this extent. For my program requirements, I had to take a 9.00 credit Humanities (HUMA) or Human Rights/Equity (HREQ) course. To make a long story short, I was sure I would lean towards the HREQ courses, as they more align with my major, but to have a better schedule, I took the HUMA 1300 course. From there, I learned about the Black Canadian Studies program, which during my first year was very new. Likely, one can guess what happened after. I fell in love with the course, joined the certificate program, and due to this, in a chain of alert/update emails regarding the program, I heard about the Robarts Centre Fellowship for 2021-2022. To me, everything I was privileged to be a part of during my third year is all because of a happy accident from my first year. My intent is to show how grateful I am for being included this year. This also is my way of saying the program and, in general, the Robarts Centre as a whole does so much for York students. For me, attending an event or being on a team for the Robarts Centre at any point during your studies is highly recommended.

Now specifically, during the year as a Fellow, I collaborated with my team to formulate one major event that really made the overall experience memorable. The 2021-2022 Fellows and I planned, organised, and orchestrated (with some help from other Robarts Centre faculty/staff) an end-of-year symposium event for our university community. It was 1.5 days, with several panels and numerous guest speakers. Many who attended the panel were our university colleagues from Trent and Mount Allison University. Honestly, it was quite stressful and closer to the date, fast paced, however, I would not change a thing. It allowed me to improve on my social networks, communication and general time management planning. It was certainly a team effort that sometimes came with disagreements. The planning and organising process was about six months on top of keeping up with studies. Including trying to manage a work, social and school life balance for myself and the other Fellows. Nevertheless, it was a great challenge, and I am happy I got that experience.

Specific to the symposium it centred around Canadianness and defining what that looks like or if it is ‘supposed’ to look like anything which brought lots of thought to our group. It was my first time doing anything this large to this extent, so I was quite anxious but also excited throughout. Although, it was teamwork that made the symposium a success, we all individually worked to create separate 1–2 hour panel events. I put together “The Black Canadian Experience: Intersections, Responsibilities and Activism” panel discussion for the symposium. My panel aimed to highlight Black Canadian voices, as this community is often overlooked and quite ambiguous. I reached out to professors and students, thought of the questions, and moderated the entire panel. For this stage alone there was a lot of ‘first’ for me that I went from being totally uncomfortable with to feeling well equipped to navigate again. Generally, I would say because of all the planning the Fellows and I did, I slowly became more comfortable reaching out to unfamiliar contacts, vocalising my opinions on subject matter, and jumping in to lead necessary decision making. I was provided with new skill sets but also got put into different (and necessary) conversations regarding Canada. Some things brought up during the symposium, but also in other events I attend throughout the year, were how as individuals and part of certain groups we position ourselves in Canada. The candid convos for sharing, learning, and understanding are something hard to duplicate which is why I have so much appreciation.

There is so much I gained from being Robarts Centre Fellow, but I will end with this sentiment. In most post-secondary institutions, you will be taught to understand the makings of the world in one specific way. Usually, this way is set by your professors, and goes unchallenged. From the experience working on the symposium to several conferences that went on during the year, as a Fellow, you really are asked how you perceive the world instead of being told how it must be. I think this is not a replicated experience you can get anywhere else so I would greatly encourage anyone who is able to participate in the Fellowship for the coming years. If not, participate within the Robarts Centre that best suits your passions and growing interest too.

That’s A Wrap: The End of My Robarts Centre Fellowship Journey

As I entered my third year as a Robarts Centre fellow, but I was not quite sure what to expect. Would the experience be the same? What opportunities for growth were there? Well let me tell you, my expectations were blown out of the water.

I specifically enjoyed that this year allowed me to connect with my Chinese heritage more. Firstly, I was privileged enough to attend the event “Searching for an Authentic: Studentification, Intangible Heritage, and Contentious Space”. This was the first step in piquing my interest in my ethnic background. I found myself intrigued by the impacts of urban planning on my culture. It was never something that I had considered, but once the presenters began a detailed discussion, I was hooked. Furthermore, I simply loved the talk because I felt represented. It was wonderful to see a group of Chinese Canadians in discussions surrounding their community and its operating systems.

Secondly, I became more in touch with my heritage as I worked on the visual essay “Canada, A Country for All?” for the undergraduate journal Contemporary Kanata. Through this work, I got to explore the historical aspects of Chinese people and their immigration to Canada. This is a subject that I have worked on numerous times, but this time it felt special because I knew it would be published, and therefore, it would be a learning opportunity for those less familiar. Additionally, I appreciated the opportunity to create a visual essay because it was something that I not previously gotten to explore in the context of a classroom. It was to be shorter and to the point whilst having the artistic pieces speak for themselves. More specifically, the format allowed me to introduce brief excerpts stating the relevance of the topic and relating it back to my personal life. I am very proud of this piece that I put out, and I hope that others can one day read it.

Lastly, this year as a fellow was fulfilling because I was one of only five undergraduate students who worked to plan a two-day symposium. The planning process was no small feat. Meetings upon meetings upon meetings, and at the end of the day, it was all incredibly fulfilling. One of the best surprises to come from this who process was the relationship that we developed with the Able York Club. This organization has been a part of York University for a long time now, and they were so gracious to help us throughout our planning of this endeavor. In particular, they helped ensure the accessibility of the two days. But beyond that, they trained us on how to be more accessible in our every day lives; and as an aspiring teacher, I hope to take those lessons with me.

In conclusion, this year came and went, and I am happy to say that I spent it as a Robarts Centre fellow. I am grateful for all the opportunities of growth that were presented to me along the way. This is sadly my last year eligible as a Robarts Centre fellow, but I am glad that this is the way that it ended. I have gone from listening to Jeremy Dutcher speak in person to planning a professor-filled panel discussion online to planning a two-day long symposium with guests from various parts of this country. I will always hold these memories near and dear.

- Renae Brady & Nera-Lei Vasilko

- Grace Deitrich

- Anastasiya Dvuzhylov

- Moboluwajidide (Bo) Joseph

- Ana Kraljević

- Dael Vasquez

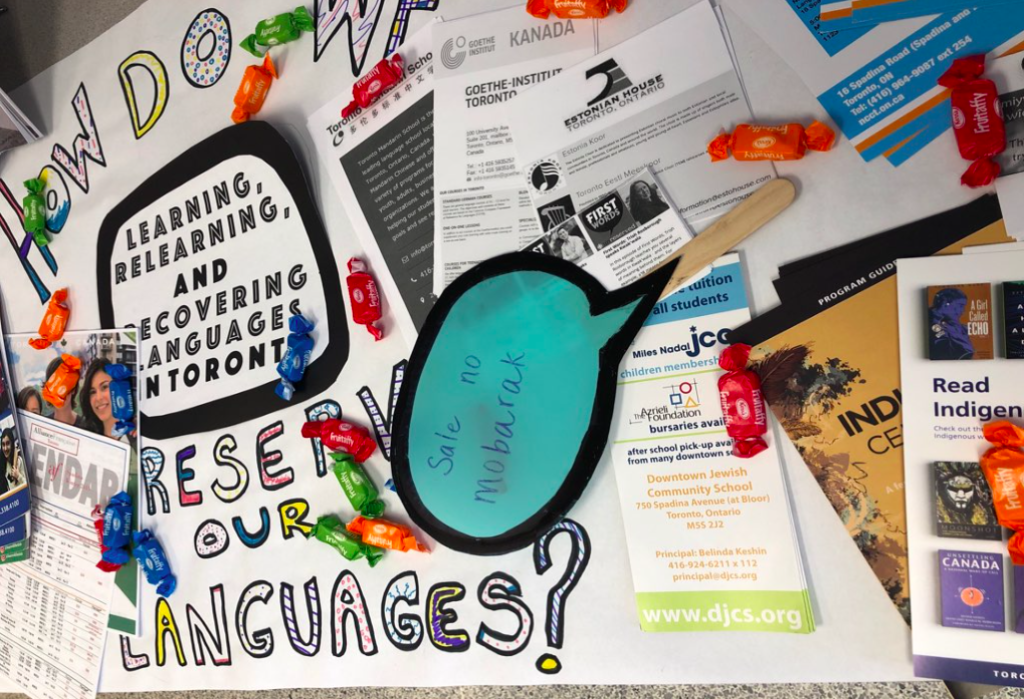

For our Robarts Centre fellowship project, we chose to look at Glendon students' linguistic diversity to get better comprehend what spoken languages are represented on our campus.

We decided to explore this topic after volunteering at the National Colloquium Glendon hosted in December 2019 on the topic of Canada's indigenous language policies in the wake of Bill C-91. In the insightful lecture by Marsha And Max Ireland on the Oneida Sign Language Project they highlighted the challenges associated with being an indigenous deaf person who was removed from her community in order to be educated in American Sign Language. Hearing her speak about the isolation she felt in not being able to hear her communities' stories really made us think differently about the importance of language. We were inspired to look at endangered languages in our own backyard.

As students studying in Toronto, we are situated in the most linguistically diverse city in Canada and one of the most diverse cities in the world. According to the 2011 census, there are approximately 200 spoken languages in our city alone and 45% of our residents speak a mother tongue other than French or English.

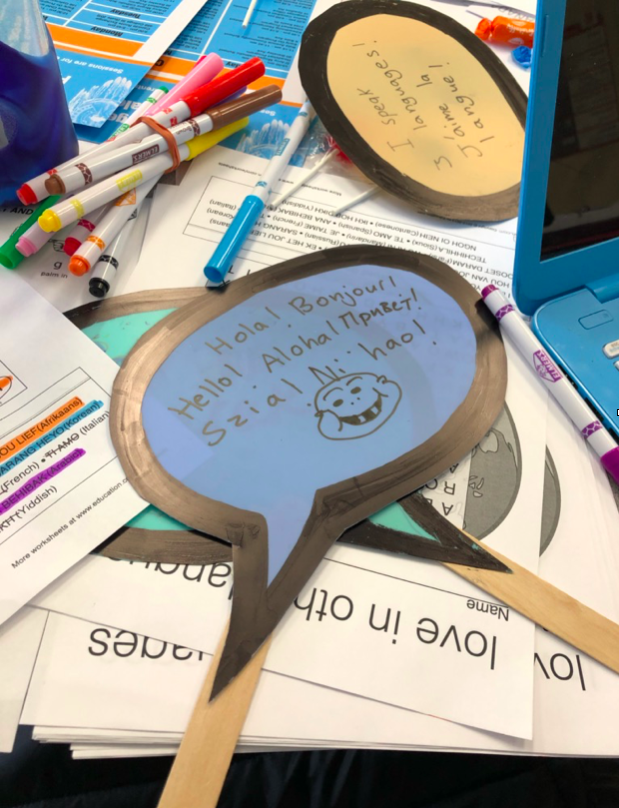

While presenting our project, we set up in the Center of Excellence at Glendon and asked students what other languages they speak at home and where in the Greater Toronto Area they reside. We also asked for students and faculty to add any words or phrases they particularly enjoyed in their spoken languages, which was a fun way to share our languages with each other. We did this to gain a greater understanding of the multitude of languages spoken in Toronto. Another area of interest for us was language education so we participants could share any languages they would be interested in learning at Glendon. The list results were varied, but some notable languages people wanted to learn at Glendon were American Sign Language, Japanese, Catalan, Korean, German, and others.

We created a map of the GTA for students to choose a sticky note to write their language spoken at home. They were then able to place the post-it to the map so there could be a visual representation of where languages are spoken. Some of the languages other than French and English spoken by our participants were; Portuguese, Croatian, Mandarin, Taiwanese, Polish, Greek, Italian, and German. This gave us a visual idea of what and where languages were.

We would like to thank Elaine Gold, Jean-Michel Montsion, and the Robarts Centre for funding our project and fostering our love for Canadian Studies.

This June, I am graduating from Glendon with a History major and Canadian Studies minor. Completing my degree during a global pandemic has been a very unique experience - I did not expect to be writing research papers from my childhood bedroom or introducing my dog to my classmates during Zoom classes. I have spent the past few weeks of quarantine reflecting on the past four years I spent at Glendon and how that time shaped me as an individual.

I started my university career at a different school, where I intended to double major in Business and Math. A few weeks into the program and I realized that it was not the right fit for me. I decided to take the year off to work and reflect on what direction I wanted to go forward in, and realized that I wanted to study subjects that did not lead to such a clear career path but would instead allow me to continue to expand my horizons. I have spent my summers working as a naturalist for Ontario Parks since I was 17, and I decided to study history, a topic I loved to explore in my programming in parks.

I was drawn to Glendon because of bilingualism, the duality of a green oasis within a busy city, and the small size of the campus. Not only is the campus itself small, but class sizes are as well. In stark contrast to the university I had previously attended, professors at Glendon knew me by name and chatted with me on the TTC. I found that smaller class sizes held me accountable to participating in discussions, because I was known by my professors and peers as Grace, not merely one of many students. There was one downside to the smaller size of Glendon and that was the limited selection of courses in comparison to the mammoth list of courses offered at Keele. Because of my previous experience at a larger university, I was determined to take all of my courses at Glendon, and I began looking at courses in other subjects that would allow me to expand my knowledge on Canadian issues. Canadian Studies courses emerged as the clear frontrunner, and I took as many CDNS credits as I had room for.

Going into my third year, I made the decision to declare a minor in Canadian Studies, and this made the last two years of my degree the most enjoyable of the four. In addition to Canadian history, I took courses on Canadian literature and politics. I took courses on the history of Indigenous peoples living in the land that is now called Canada and each summer I returned to my job at Ontario Parks inspired to improve my programming and apply my new knowledge. In my fourth year, I was a Robarts Centre Fellow and this experience made me really appreciate the community that I was a part of as a Canadian Studies student at Glendon. I attended book launches for both Victoria Freeman and Colin Coates, two professors I was lucky enough to have during my time at Glendon and have immense respect for. The network of people that the Fellowship has provided me with the opportunity to meet is invaluable, and is by far the part of this experience that I appreciate the most.

At my prior university, everyone in the business program had nearly identical goals and the biggest difference was between those who wanted to be accountants and those who planned to enter marketing. At Glendon, I have appreciated how broad the interests of my classmates are within a single subject. I took Canadian Studies courses with the desire to broaden my historic knowledge of Canada within my position as a naturalist, but I have truly enjoyed studying alongside classmates with goals different than mine. I have learned a tremendous amount from my peers who are working towards careers in diplomacy and politics and think it is amazing that students with such a broad scope of interests have all found Canadian Studies courses that applied to them. I think that no matter what a student’s goals are, extending their knowledge of Canada’s history, culture and political structure only stands to benefit them.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a trying time for everyone. However, I’ve found one silver lining. While galleries, museums, and other public institutions have closed their doors, their online presence has flourished. You can now take virtual tours of almost any museum from the comfort of your couch. It seems that history and especially local history is becoming more and more accessible.

The term accessibility, especially when used within the realm of history, brings to mind digital archives, open-source resources, and even physical things like barrier-free access. The ROM has elevators, the AGO has ramps, what more could you ask for? The thought of accessibility hadn’t crossed my mind until I attended York University’s 7th annual Public History Symposium at Todmorden Mills in November 2019. The theme was "Access and Inclusion in Historic House Museums" and featured keynote speaker Niya Bates, Director of African American History at Monticello Museum in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Bates brought up several interesting points on what kind of history is being presented. When we talk about the importance of heritage preservation, we often overlook what gives something more historical significance over another, and what community it caters to. It’s easy to look at old photos and lament all of the significant architecture prior to the conservation movement picking up in the later half of the 20th century, but what is important is to make proper use of what has been preserved and make sure that it tells an accurate story.

While this seems reasonably simple, it is much more nuanced than that. Bates described the current programming at the Monticello Museum as a 45-minute guided art deco tour of the house and then guests can explore the property as they please. No part of the tour really addresses the plantation or the lives of the slaves who had lived on the property except for the last room in the tour which had been converted into a quick debrief of the history. If guests want to know more, they are free to explore and read signage around the museum property.

This came as a bit of a shock at first, only a handful of people had lived in the actual Monticello house while the plantation housed over 150 slaves, yet their stories were made far less prominent. This is at no fault of Bates or other curators of course, Bates said that the reasoning behind this was the demographic of the guests that visited the museum. It was mostly older white people wanting to know about Thomas Jefferson’s life.

Heritage conservation comes with a hefty price tag. It isn’t easy to maintain any historic landmark and a lot of funding comes from grants and donations. I saw this firsthand very briefly when I volunteered at the Campbell House Museum in Toronto as a part of Robarts Centre fellowship. The museum relies on grants and is also available to be rented as an event space. The house itself has an interesting history, being moved from its original plot of land to the corner of Queen and University, saved from demolition by the Advocate’s Society. Although it was a historic house museum, it was viewed as a legal hangout by most.

After the city’s acquisition that stigma faded but even today, the tour is similar to how Bates the one at Monticello. It is about an hour long and tells the life of Sir William Campbell and a bit about his wife Hannah. It talks about the history of the property leading up to the acquisition of the Advocate’s Society and the house in present day. It is decorated with all period-appropriate furniture, with a dining room, a withdrawing room, ballroom, and bedroom. The servery has been converted into an office, and the attic servants’ quarters was renovated and turned into storage. Unfortunately, no photos were taken of the quarters prior to the renovations, they have been lost to time. The original kitchen had been lost when the house was moved from its original plot, but the fully restored replica offers a glimpse into what a servant’s life would have been like.

The history of the house itself is fairly straightforward, it housed Sir William Campbell and his wife until their passing and was passed off through many hands. The fact is that most visitors are people who pass by and come in out of curiosity. There isn’t much attraction for children, and given the age of the house, it isn’t physically accessible for all. While the house has some flaws, it’s a standing testament to Georgian architecture and a significant milestone in conservation.

These two experiences greatly shaped my experience as a Robarts Centre fellow this school year. Accessibility isn’t limited to just the physical realm; accessible history demands that all voices are heard. I’ve taken to thinking more critically about what kind of history is being presented and what is being omitted, what is deemed worthy of preservation and what isn’t.

Sara Ahmed in Queer Phenomenology writes: “seeing oneself or being seen as white, black or mixed, does affect what one ‘can do’, or even where one can go” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 112). Employing the ideas of Frantz Fanon, she discusses race and space in a very detailed chapter on the Orient and others. In reflecting on my brief time as a Robarts Centre undergraduate fellow, against the backdrop of a rise of protests and actions that pivot around the concept of black bodies and the limits imposed upon them, these words serve as a necessary entry into how I have come to frame my time. Certainly, I find myself returning to the quiet retreat from the city up in some woods in Northern Ontario with other students and Canadian studies scholars from Glendon and Trent, grappling deeply with my identity and possible paths forward.

I was not born ‘black’. In many ways I became black upon moving to Canada and retracing the steps of others before me across the Atlantic. My blackness and the half-obscured histories and legacies of Black-Canada were inherited upon immigration, after the fact. And for as long as I have stayed in Canada, I have had to wrestle both with the violent history of the Canadian state in its approach to First Nations, Inuit and Metis people, but also with how I fit into its promise of tolerance and acceptance enshrined in its policy of multiculturalism. To negotiate my desire to belong in a country scaffolded with systemic injustices.

As an only child with only myself for company, I have had to rely on novels to teach me much about the world I inhabit. The Canada I came to know in high school through the words of Richard Wagamese in Indian Horse, or in university through Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black, Zalika Reid- Benta’s Frying Plantain or Dimitri Nasrallah’s Niko, was not the Canada I or my family had quite imagined it to be. I realized sitting in my classes on Contemporary Canada and Canadian literature that this place I had chosen to become my new home required further introspection on, and new tools to take on the struggle of justice.

I think if I have taken anything away from my fellowship, it is that Canada like everywhere else needs thinkers committed to the process of learning about it. I have had the rare opportunity and privilege to do so in a space built to support questers ravenous for the truth. The chance to work with other organized research units like the Harriet Tubman Institute for Research into Africa and its Diasporas and its Director on projects dually meaningful to me: personally, and politically. To imagine myself living in a land where we are all liberated, immigrants and Indigenous to go where we want and do whatever we desire.

But mostly, when I think of my fellowship, I think of rowing a canoe on Kushog Lake, and peering into it layered depths. I can feel the sun on my face and feel the push and pull of the water straining against my muscles as I listen for the calls of nature in the whistling wind. I am afloat in that bone deep quiet and reaching like so many others towards the land. Towards, I imagine, a fully known Canada where we can all be free.

It has been an immense honour to serve as a Robarts Centre Fellow for my second consecutive year at Glendon College. I must admit that this is an incredibly challenging time to write this blog post due to the exhausting level of global despair that has arisen from an inherently unjust societal order. Our globalized world continues to be plagued with inequities that are far more atrocious and demeaning than the coronavirus pandemic, and it has thus become tiring to remain hopeful in an increasingly hopeless world.

I hope to reread this blog post in 30 years and happily reminisce about the intellectual enlightenment that this research institute has encouraged me to benefit from. I can already imagine my wiser self sitting comfortably on her rocking chair, looking back and remembering all of the Robarts-sponsored events and opportunities that she was privileged to engage with. I invite you to join me on my journey as I look back and reflect upon some of my personal highlights as a Robarts Centre Fellow this year…

Canadian Studies Retreat with Trent University. This retreat saw the intellectual union of two small cohorts of university students from Trent and York University who all study, and are passionate about, Canadian Studies. I attribute the success of this retreat to the brilliant coordination and execution of the Canadian Studies community at Trent, as well as the willingness of the Canadian Studies administrative body at Glendon to provide its students with such an enlightening and rare experience. In particular, this retreat would not have been such a success for Glendon students had it not been for the genuine leadership of Professor Colin Coates, who voluntarily sacrificed his weekend to ensure the intellectual fulfillment of his students. It is individuals like Colin, in addition to many of his colleagues, that makes me proud to be part of the Canadian Studies network at Glendon. Aside from canoeing on Lake Kushog, what I enjoyed most from my experience was when both groups huddled around the fireplace to engage in a thought-provoking discussion around the 21st-century priorities and challenges for the discipline of Canadian Studies, and where my generation positions Canada in 50 years. Our authentic discussion lasted for a few hours, and we would have prolonged it had it not been for our grumbling stomachs. It is also worthy to mention the lack of social hierarchy that existed within our circles, as well as the unbreakable bond formed between the students from both communities. Students were attentively listened to as if they held the same power of contemporary Canadian leaders. As a result of current public health precautions amid the global pandemic, the Canadian Studies cohort at Glendon is no longer able to host a follow-up retreat, but I do anticipate and hope to be able to engage in a future retreat with the Trent community in the near future.

Ministerial Job Shadowing. It is thanks to my fellowship in this research institute that I was immersed to the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario’s job shadowing program. I was fortunate to have served as a job shadow at the Ontario Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries this past February. I met numerous high-profile ministry employees and politicians who were very generous with their time and experiential advice, weakening the sense of professional hierarchy that existed between us. It was incredibly rewarding to educate myself on the significant, yet at times undermined, work of these public servants, and to even be able to maintain a friendly and professional relationship with them after my time as a ministerial job shadow. I was also invited to attend a few ministerial meetings that ultimately facilitated my educational engagement with distinct forms of Ontario legislation, such as the Ontario Heritage Act, policy development, heritage education and outreach, as well as archaeological licensing and regulation.

Interruptions Due to the Coronavirus. There were many intriguing Robarts-sponsored events that I was hoping to attend before public health and physical distancing measures were enforced in Toronto as a direct response to the coronavirus pandemic. I was looking forward to engaging in the Glendon Global Debate, the Canada Reads Screening on Jesse Thistle’s From the Ashes, the Glendon Research Fair, the Graduate Student Conference and of course, the follow-up retreat with the Canadian Studies community at Trent University that was expected to take place sometime in early April. It is unfortunate that some of these events have been cancelled indefinitely, but I hope that the others are able to take place in the near future.

My Hopes for a Post-Pandemic Canada. I aspire to live in a post-pandemic Canada that acknowledges its inequities and continuously fights to dismantle the colonial systems of oppression that sustains them; a post-pandemic Canadian society where people understand that our current socio-political systems were inherently created to benefit a select few members of our society. I hope to live in a post-pandemic Canada that recognizes, instead of hierarchies, its essential workers, including grocery clerks and the brave men and women who serve in our medical fields. I would like to live in a post-pandemic Canada that actively seeks to eradicate homeless encampments, instead of sitting idly and accepting this sense of inopportune fate. I hope to live in a renewed Canadian society that uses its power to evoke positive societal change in our country. I look forward to a post-pandemic landscape where Canadian Studies enthusiasts and researchers are encouraged to join forces and create publications, workshops, open events and conferences that touch upon our collective expectations for a post-pandemic Canada and global order. I also hope to see an interdisciplinary expansion of the Black Canada research cluster of the Robarts Centre facility.

I appreciate the time that you have taken out of your schedule to read my blog post, and I hope that the feelings that I evoke in this commentary will lead you to set your own expectations for a post-pandemic Canadian and global society. I leave you with what Helen Keller once said: “We may have found a cure for most evils; but we have found no remedy for the worst of them all, the apathy of human beings.”

I would also like to do my due diligence and thank the Robarts Centre administrative team for their tireless efforts and continuous support during my two years in this fellowship. In particular, I would like to extend an immense sense of gratitude to Jean Michel Montsion for his genuine support and leadership, as well as Anastasiya Dvuzhylov for our intriguing discussions and planning sessions as senior Fellows.

Stay safe; and let’s try to remain hopeful in an increasingly hopeless world,

Ana Kraljević

Atop an intricate and diverse global landscape rests the Canadian landmass. Unassuming in the eyes of allies and unthreatening in the glare of rivals, Canada is a state which at first glance does not pose an interesting subject of analysis. After all, as Marshall McLuhan famously said: “Canada is the only country in the world that knows how to live without an identity.” Indeed, when compared to other nations rich in culture such as Bangladesh; famous for their technological advancements to the pace of South Korea; or renowned for their abstention of bellicosity, such as Switzerland, Canada appears to be rather formless. Perhaps the greatest irony of this nation is that its imposing geography does not reflect its status relative to the rest of the international community. So how does one respond then to the inevitable question: why do you give any consideration to Canadian Studies? I believe to answer this question, those majoring in the discipline must look towards what they have identified as meriting thorough observation. While I cannot speak on behalf of Canadian Studies students, my contribution to defending the significance of studying Canada begins with an account of my exposure to Glendon’s unique interdisciplinarity.

Like many who are new to university, as a post-secondary neophyte, my comprehension of social phenomena was proportional to the quality of my educators; those passionate about their craft tending to be the best - as anyone with a favourite professor can attest. Through good fortune, I was able to meet such an educator in my first year - a man with a warm smile and unrivalled generosity, Dr. Colin Coates. Through his lectures on understanding contemporary Canada, my conception of this country was fundamentally reconstituted. Already being familiar with the country’s colonial legacy, its treatment of Indigenous peoples, and the schism that continues to exist between Quebec and the Rest of Canada, Dr. Coates provided a fresh perspective on the amusing nuances of Canadian identity. It was there that I was formally introduced to the relics of the Group of Seven and was able to look at one of Canada’s most famous icons - the Mountie - through a critical lens. Certainly, for many people, neither of these two entities constitute anything particularly new. Not only because both have existed for decades - with the memory of the former preserved in their art - but ostensibly, because there does not appear to be anything unique about either. A myriad nations have had great painters: Austria’s Gustav Klimt, Netherlands’ Vincent Van Gogh, and Spain’s Pablo Picasso being among the world’s finest; and in an era where “police brutality” has become ubiquitous in popular vernacular, one need look no further than Derek Chauvin (the former Minneapolis police officer charged with the murder of an unarmed black man in his custody) to see how a police force can become a stark symbol of a country’s brand. Yet, for someone who would later go on to become a political-communicologist, these lessons proved to me that Canada is not the cultureless taiga some purport it is.

At the turn of my third year, my time with Dr. Coates had long passed, but I had an equally wonderful opportunity to meet my next mentor in Canadian Studies, Dr. Jean Michel Montsion. As the Deputy Director of the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, he helped me find the experiential learning opportunities I sought and gave me the chance to apply the knowledge of previous years into action. Under his tutelage, I became a Robarts Centre fellow and commenced a year-long dialectic with the question of Canadian identity. The first activity I partook in was a retreat with students from Trent University at a cottage by a lake. There, Dr. Coates made his return as our proverbial guide on a journey of learning. Immersed in the Canadian wilderness, both cohorts from Glendon and Trent came together to discuss the most important matters of our time: democratic participation among youth, climate change, and most significantly, the legacy of William Lyon Mackenzie King - the Prime Minister who came to define our nightly rounds of Canadian trivia. This encounter proved to be more instructive than I had previously imagined. Over the course of three days, the professoriate accompanying us delivered brief lectures to help stimulate thought and discussion on some of the topics mentioned above. Succeeding this experience were a series of lectures held across both Keele and Glendon on subjects such as Canadian international security, Chinese ethnicities in Vancouver, and an illustrious talk on the Toronto housing market that, due to COVID-19, never came to be. However, the most pivotal moment in my fellowship arose from my acceptance to the Bridgewater University research conference. Honoured to represent the Robarts Centre as York University’s only delegate, I wanted to make an impression on the American dais listening to my analysis - the pleasure of which COVID-19 would also take away.

Tasked with producing a research paper to present on a panel, I turned towards the question of Canadian identity once more to help illustrate the contours of its figure. However, while the political scientist in me wanted to explore interstate hegemony, the communicologist sought to study mass media and semiology. Ultimately, a compromise was reached and the paper I wrote analyzed Canada’s use of soft power in exerting influence on foreign nations. While the focus of the essay was to describe the methods employed by Canada, my research offered a glimpse into why Canada is perceived in terms as simplistic as “cold” or “empty”, and why only certain elements of Canadian culture are thought to be representative of the national ethos. In Evan Potter’s Branding Canada: Projecting Canada's Soft Power through Public Diplomacy, he argues a lack of funding and visibility of Canadian media and public acts to be the reciprocal causes of Canada’s relative loss of international identity. This leaves the portrayal of Canada susceptible to misrepresentation by foreign media - film, television, and now, streaming. Without the means to successfully disseminate a counter-narrative and contest the depictions made by foreign multi-billion-dollar entertainment industries, a Canadian’s perspective of their national identity is ultimately defined by what foreign actors describe it to be.

This reality is not new. Indeed, Canadian Content (CanCon) and the Music, Artist, Performance and Lyrics (MAPL) system were created to protect national media against the pressures of external cultural hegemony. These are important realities to contend with, if only to add to one’s own repository of knowledge. However, what I wish to leave with you, is that Canadian Studies is a valuable field of research. If one were to interpret the study of Canada through a neo-colonial lens, they would quickly see how our comparatively small nation is facing a threat of erasure comparable to the travesties Indigenous populations were subjected to by early settlers. Thus, if we are to preserve the mosaic tapestry of our troubled but peaceful postmodern peninsula, we must reflect upon the state of Canada with the rigor necessary to elevate Canadians to the highest level of erudition. For our benefit, both in theory and in practice, the Robarts Centre’s fellowship program and its excellent group of professors serve precisely to accomplish this aim.

- Victor Dumont

- Anastasia Dvuzhylov

- Elzbieta Gach

- Ana Kraljević

- Katherine Mazzotta

- Rachel McCurrach

- Jocelyne Mitchell

- Daniella Prandoczky

- Dea Thompson

Canada, trois syllabes et le grand inconnu, ou le grand méconnu. Canada, quelques images en têtes : les grands espaces, le froid, le Québec. Voilà ce qu’étais ma connaissance du Canada avant de venir. Maintenant, ma vision est tout autre. Grâce à mon année universitaire passé au Collège Glendon de l’Université York de Toronto, et ma participation au programme de recherche du Centre Robarts (ai peu découvrir beaucoup de choses.

Voici donc, le Canada, tel que je le perçois aujourd’hui, sous forme d’Anagramme Le Canada, c’est d’abord la Curiosité intellectuelle. Qu’il s’agisse de penser les villes intelligentes et inclusive, de concevoir un TGV entre Montréal et Toronto ou encore de réfléchir aux enjeux de communication interculturels, il y a toujours des personnes prête à s’intéresser à des sujets à nul autres semblables.

A, comme accueil. L’accueil, ce fut celui des Premières Nations qui ont permis aux arrivants européens de survivre. L’accueil, c’est également le caractère multiculturel qui se construits des apports de nouveaux citoyens du monde entiers, permis par la politique du multiculturalisme. L’accueil, c’est l’hospitalité amicale et chaleureuse qui m’a été offerte à Glendon.

N pour Nations et plus particulièrement, Premières Nations. Ces peuples, représentés dans la culture occidentale au travers d’une imagerie grotesque et insultante, sont extrêmement divers. J’ai eu l’occasion d’apprendre un peu à propos d’eux. Bien loin d’être des « sauvages », ils possèdent des valeurs précieuses : valorisants l’auto-apprentissage, la non-violence, l’autonomie, la coopération et la solidarités, l’importance des liens intergénérationnels, la communion et le respect de la Nature, le respect des ainés, l’égalité et le respect entre les femmes et les hommes, ils semblent avoir dans leur mode de vie des valeurs éthiques essentielles qui font malheureusement toujours défaut à la société occidentale. En outre, ils possèdent une culture et des langues d’une incroyable diversité, se battent avec beaucoup de dignité pour leur préserver et ont su rester dignes, malgré les méfaits considérables de la colonisation.

A comme avancée. C’est l’entreprise difficile de la Commission de Vérité et de Réconciliation qui vise à retisser peu à peu le lien entre la société canadienne Mainstream. C’est l’écoute, l’ouverture d’esprit, la franchise, la remise en question, la volonté de reconnaitre l’autre dans son identité et dans son humanité, c’est la bonne foi, c’est un chemin difficile, qui n’est pas tout droit tracé, mais qui finira par conduire à l’harmonie et la guérison.

D pour diversité. Diversité des langues : deux langues officielles, plusieurs groupes de langues autochtones et plusieurs langues du monde qui se développent avec l’immigration, diversité des paysages, de la Vallée du Saint-Laurent au Lac Ontario en passant par la rivière de l’Ouatanais. Diversité des destins des personnes que j’ai pu rencontrer. De l’émouvante épopée de Kim Suy et l’amour qu’elle a développé pour la Langue Française à l’enthousiasme de David Colonnette pour son projet de TGV ou en passant par le récit généreux et affable de Deborah Mac Gregor lorsqu’elle nous a raconté l’histoire de sa langue et de son peuple. Diversité des cultures qu’a constitué pour moi la plongé dans le grand bain multiculturel qu’est Toronto.

Un dernier A pour l’apaisement : apaisement du débat politique, avec une culture de l’écoute et du respect de la diversité d’opinion, avec la volonté d’inclure le plus grand nombre à la société, quel que soit son origine, son état de santé ou son handicap, quel que soit sa religion, son orientation sexuelle ou son identité de genre. Cet apaisement des tensions vient également de la croyance durement ancrée dans l’esprit des canadiens que la diversité est une force. Alors que dans beaucoup d’endroit du monde, chacun se replient sur son identité et tout semble enclin à la décision et aux clivages, le Canada délivre chaque jour le message inverse avec une portée remarquable. L’apaisement c’est donc en partie les accommodements raisonnables qui visent à concilier le projet de société avec les valeurs de chacun. C’est un respect profond des individualités sans que le collectif ne soit abandonné. L’apaisement, c’est aussi la volonté de regarder la vérité avec lucidité et sans fard, en ce qui concerne les deux grands points noirs de l’histoire du Canada : les mauvais traitements infligés aux Premières Nations par le gouvernement fédéral et aussi, la mise au banc économique et sociale du peuple fondateur français par le colonisateur d’origine britannique.

L’apaisement c’est également la sérénité que l’on peut trouver en contemplant la beauté de la nature sauvage pour peu que l’on se rende dans n’importe quel parc canadien. Un spectacle souvent à couper le souffle qui permet de se vider la tête et de mettre à distance les tracas de l’existence humaine. L’apaisement, c’est semble-t-il aussi le chemin que va prendre la population canadienne, dans un rapport respectueux vis-à-vis d’autrui et de la nature. C’est aussi un comportement qui s’impose lorsque l’on doit lutter contre un climat hostile.

Pour illustrer cet impératif, je voudrais citer Louis Aragon afin de conclure cette note introspective :

« Quand les blés sont sous la grêle

Fou qui fait le délicat

Fou qui songe à ses querelles

Au cœur du commun combat »

La Rose et le Réséda.

Shop local? Watch local.

There has always been a sense of pride associated with ‘Canadianness.’ Whether it be cheering on the Team Canada or buying a bottle of VQA wine, people are proud to be Canadian and are proud of Canadian exports. This phenomenon is also visible on a consumer level. Grassroots efforts to shop local and support small businesses are evident in community markets and events.

The effort to keep it local is reaching a mainstream level, but why hasn’t this effort reached Canadian film and programming? CanCon (Canadian Content) is often seen as boring and quaint, and thought to be directed towards boomer audiences. While young creators are pointing out the faults in the system, campaigns like MADE | NOUS are striving to change that.

MADE | NOUS is a collaborative effort from the Canada Media Fund (CMF), Telefilm Canada, and other industry giants. The campaign’s goal is to promote CanCon and the people behind it. Boasting a strong social media following, they promote rising stars and Canadian classics, as well as hidden gems. The campaign takes it a step further too(remove too?), with an interactive map on their site that shows where major films and programs are produced.

What exactly is Canadian Content or CanCon? The CRTC sets out several key criteria to receive Canadian Program Certification. This includes the producer n, either the director or screenwriter and one of two lead performers being Canadian. Additionally, a minimum of 75% of program expenses and 75% of post-production expenses are paid for services provided by Canadians or Canadian companies, among others.

While key players like Telefilm and the Canada Media Fund (CMF) find that this system works, young Canadian artists like filmmaker Matt Johnson, disagree. In an interview with Radheyan Simonpillai, Johnson, points out the flaws in the CRTC’s system. Funding for his film, Operation Avalanche, was rejected by Telefilm, but a movie like Room was financed, although the people making it weren’t Canadian. As a result, Operation Avalanche was picked up by an American distributor.

“What happens is that the international producers use Telefilm, our financing system. They say, ‘we will come and shoot our movie in Canada if you agree to give us this money from Telefilm,’” says Johnson to Simonpillai.

This isn’t the first time the filmmaker has spoken up against the major players in the Canadian film game. In another interview with Calum Marsh, he hits on other flaws within the current system. “You have a dozen filmmakers who, no matter what, are going to get funded by Telefilm and, no matter what, are going to have their world premiere at the biggest festival in the world,” a nod to the unchanging roster of names at the TIFF galas every year.

While Johnson may sound cynical, he’s revolutionizing film and content making. His first hit, The Dirties, has become a cult classic. As a film student Johnson had a budget of a mere $10,000 for the film. His webseries Nirvanna the Band the Show was turned into a television series on Viceland. He has quickly become one of the biggest advocates to make filmmaking more accessible. Another young filmmaker, Kevan Funk, steps away from Johnson’s ‘burn down the institution approach’ and sees hope in a system he also considers flawed.

Funk allowed his response to TIFF Artistic Director Cameron Bailey ’s editorial piece to be made public. Bailey called on Canadian filmmakers to make films about us not just themselves. Funk saw this as a problematic demand in a country where Canadian distributors and broadcasters tend to be disinterested in these types of narratives, something that he himself experienced first hand.

The constant ragging on the Canadian film industry becomes problematic to Funk as well. “It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. If Canadians are only hearing about how terrible Canadian films are, I'm not surprised with the lack of interest that they have in searching out our work,” he states.

Although the MADE | NOUS campaign strives to showcase Canadian talent, it often focuses on the big names, one of the issues brought up by Johnson. Their site even features Room, a movie with an Irish director. A force funded by the film giants, the campaign won’t bring change or awareness to the issues faced by Canadian filmmakers. All it can really do is showcase their talent. While it’s refreshing to see how many mainstream films and shows are classified as Canadian, it begs the question of if they just found a loophole to be able to bear that label.

The Robarts Centre Fellowship was a great program that encouraged me to think about Canada outside of my history major. It was both a nice mental exercise and a good way to learn about the events going on around the university. One of the components of this program was to attend presentations about Canada. I attended four presentations, on Glenn Gould, on Smart Cities and Toronto, on treaties and land issues, and on food sustainability. I originally went into this program with the hope that I would learn more about Canadian history in particular, but ended up learning more about contemporary issues in the latter three presentations. This was a pleasant surprise. A lot of the topics in the three presentations were on Toronto or Ontario, and I heard about some initiatives going on, such as community-based environmental movements.

The Glenn Gould presentation was the most historic of the four, and I did enjoy it. I hear about Glenn Gould often on the CBC and in books, but I actually knew very little about his life. The most interesting thing about the presentation, however, was that it was presented by a person not from Canada, but from Japan. It always surprises me when people abroad take any interest in Canadian issues or histories.

Another component of this program was to participate in some sort of volunteer activity. I volunteered in a group with three others to create a booth showcasing Toronto’s and Canada’s linguistic diversity. We set up in front of Glendon’s cafeteria for two afternoons and offered information to students about language resources around the city. We also tried to start conversations with students about what they do to learn, re-learn, and preserve languages. I had some great talks with students who’ve had different experiences with languages - some who hated learning them and some who loved it, some who were preserving their languages through their children, and some who struggled to re-learn their native tongues. I am part of the latter group, and it was nice to talk to other people about the strange difficulty of forgetting your first language.

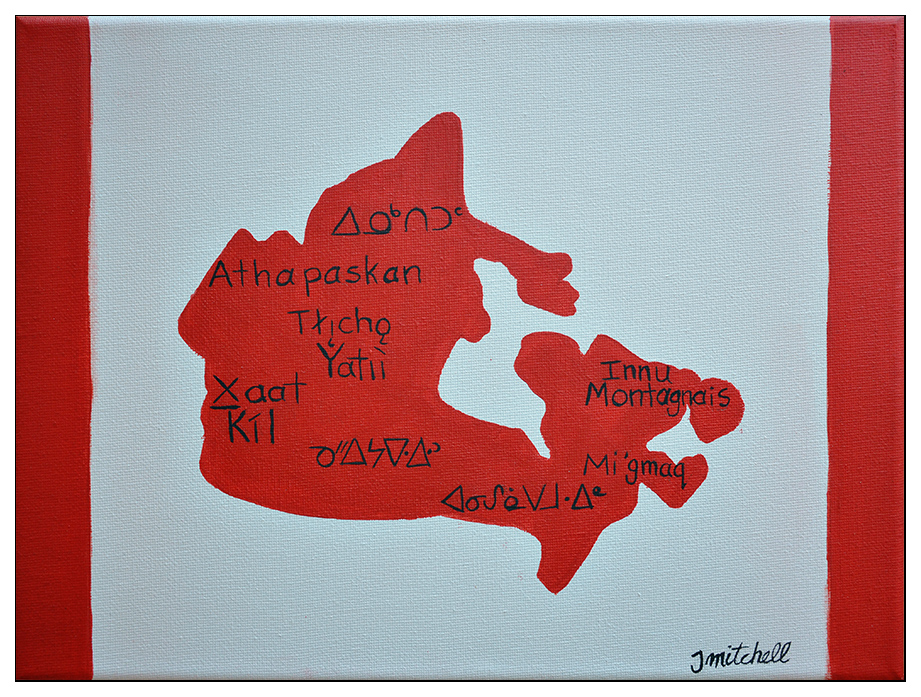

What stands out most to me from this experiences is all of that maps that I looked at that showed the linguistic diversity of the country.

While I am more aware of language trends in southern Canada, I do forget about the north’s diversity. Northern Canada tends to be a homogenous blur in my mind, but these linguistic maps, which showed the differences in Indigenous languages in the north, helped to break apart that image. Canadians in cities tend to be very south-centered, and it is quite a mental exercise to stop thinking this way. Thinking about linguistic populations was one way to stop thinking about the south as if it is the core of the country.

While I had already finished my volunteering requirement, I later volunteered at the Graduate Conference, just because I wanted to know how a conference worked. This was something that I looked forward to and I was not disappointed. It was nice to see such a group of people with similar interests.

Overall, I did learn a lot about Canada, both about its past and its present. However, the most valuable thing that I learned was that all of these events go on around campus. Normally, when I want to learn about something I look for a book about it, and I usually avoid talks and events on campus. I now know where to look when I want to hear about and discuss ideas on a topic I’m interested in, and will definitely attend more events next year.

My Sense of Gratitude for Robarts

My name is Ana Kraljević and I decided to join the Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies for quite a few diverse reasons, but before I dive deep into what they are, I find it appropriate to first introduce myself. My passion for world history began when I found myself more and more engaged during my elementary school history lessons. Learning about a society that is outside of my reach always sparked and continues to spark my curiosity as an adolescent. I am currently pursuing an undergrad in French Studies with a Bachelor of Education, as well as a minor in Canadian Studies, at Glendon College, and I just completed my first year. Having the privilege to dedicate my student life to studying two of my biggest passions is something that I will never take for granted. Education is the key to the glass door of drastic social change and I believe that the study of history has the immense power to challenge conventional world views.

On November 13th, 2018, the launch of the Robarts Centre Fellows was held at the Canadian Languages Museum at Glendon. I had three classes on the day of the launch and was extremely tired, but I knew that deciding to skip would result in a huge regret, and I was right. This launch was the perfect occasion to meet multi-disciplinary students, each with their own diverse and intriguing history, who all ultimately valued the power and study of history. More often than not, I have had a difficult time encountering people my age who find an interest in and are passionate about history, especially Canadian history. Although there might exist many speculations as to why younger generations fail to understand the importance and power of history, I tend to trace this lack of interest to a failure on behalf of our education system. History should not be treated as a school subject, but as a way to understand societal changes and how future generations have the power to reshape their world by studying the mistakes of the past.

The fact that Glendon is bilingual allows and encourages me to frequent a number of on- campus events that are conducted in one or both of Canada’s official languages. Robarts Centre Fellows are required to attend just two events throughout their academic year and I am grateful to have been given a series of various distinct and intriguing opportunities to choose from.

On November 21st, 2018, I attended a discussion in French that analyzed, “la pluralité des savoirs dans Wikipédia,” which translates to, “the plurality of knowledge on Wikipedia.” It was very interesting to learn about the complex intricacies of a website that I use so often, but never found the occasion to research about. The small group of participants led to a tight-knit atmosphere where everyone was encouraged to freely express their opinions and arguments. My level of French in November was nowhere near where it is currently, hence I was thankful that the presenter spoke at a speed that was understandable for all of the attendees. The presenter discussed the specific details of how Wikipedia is governed and the reality that many intellectuals believe that the use of Wikipedia is dangerous since anyone with Internet access is able to add and modify any given information. In addition, I learned about how the Atikamekw, a First Nations group, worked collectively with members outside of their community to create a Wikipedia page about their culture and history, all in the Atikamekw language. One of their principal difficulties was the direct translation of many English words that do not exist in the Atikamekw language. This project was created with the intention of educating members of the Atikamekw community about their history and culture in their own mother tongue. Compared to other Indigenous languages, the Atikamekw language is not under threat as it is spoken daily by its population, however this site has the direct effect of preserving their language, as well.

In addition, on February 28th, 2019, I attended a presentation by Jeremy Dutcher, an Indigenous composer and activist of the Tobique First Nation, on the significance of linguistic revitalization and the power of music in his community. He discussed how his Indigenous language is under threat, and how losing a language leads to the loss of an entire world view and one’s relationship to the land. He and his team has had an instrumental role in preserving many Indigenous pieces that were created by elders on wax cylinders. Unfortunately, these cylinders degrade as they are overplayed and he consequently lost one third of the songs. At first, Dutcher did not feel as if he had the right to sing the songs, but then he realized that it was not about him saying what he wanted to say, but letting the archives speak for themselves. Although there only exists less than 100 fluent speakers left, Dutcher does not see his language as dying nor does he like to be seen as someone who is saving his language. He left his community when he was 17 and soon realized that at times, fitting in everywhere means fitting in nowhere, and he admitted that the work that he is doing today was not even imaginable one generation ago. Past and current Indigenous narratives have always sparked my interest and Dutcher’s presentation was unique in the way that he did not conceptualize the dark past as so many intellectuals have done and continue to do today. He drew a picture of his community in the present, not in the past, and he discussed a world of cultural belonging without borders.

The graduate student conference and closing event for the Robarts Centre Fellows took place from May 3rd-4th, and I participated as a volunteer. I worked with other fellows to greet and direct the attendees and panel hosts to their respective rooms, as well as answered their questions concerning the schedule of the conference. In addition to being a volunteer, I was also granted the opportunity to join any panel that sparked my interest, and I did just that. I attended a panel regarding the politics and specific laws pertaining to sexual assault on Ontario college campuses, as well as the court case concerning the death of Cindy Gladue, an Indigenous women from Edmonton, in June of 2011. The two discussions were distinct and similar in their own ways, and I truly enjoyed the fact that both of the panelists did not try to speak on behalf of their victims nor take control of their respective narratives. The closing event began shortly after the end of the graduate student conference and it was a great opportunity to socialize with other fellows and compare our experience as fellows throughout the year. Many of us discussed our introspective work, as well as the skills that we gained as a Robarts Fellow. In relation to my introspective work, I was given the opportunity to work on an Indigenous Languages booklet for the Canadian Languages Museum at Glendon with a very close friend. Being able to work collectively on my introspective piece with a friend made the experience even better and we were encouraged to educate each other along our journey. We learned about the various linguistic differences between distinct Indigenous groups across Canada and most importantly, we learned the danger of stereotyping all Indigenous languages as one entity. In reality, all Indigenous languages are fruitful with their own abundant history and culture.

Being a Robarts Fellow during my first year of university aided me in acquiring many valuable skills, such as time management, effective note taking and organization skills. The Robarts Centre is much more than a research centre for me and I believe that one of the reasons as to why I enjoyed my first year so much was due to my participation as a Robarts Fellow. I thank every single person that has had an impact in making this program a reality, and a special sense of gratitude is given to Jean-Michel Montsion for always being engaged and interested in making the experience of each fellow as amazing as it could be. I have very high hopes for the Robarts Fellows and I wish to see this pilot-project progress throughout my time at Glendon. I also hope that this program grows in numbers and that more and more people begin to value the true power, significance and complexity of history in our past, current and future societies.

My Robarts Fellowship Experience

Why did I join?

Honestly, I wasn’t 100% sure if joining a fellowship in my first year of university would be the best fit for me. But in the end, it was hard to say no to anything involving Canadian studies.

What will I have to do?

Before coming to a decision as to whether I would officially join, I had to figure out if I really wanted to do all the required components. The answer of course was yes. For this impressive fellowship I would be required to attend two talks on campus that were related to Canadian studies. Then, I would need to do some volunteer work, and finally, an introspective work which is this here blog post.

Wikipédia et les Attikameks

La première des deux présentations que je suis allée voir était celle de Wikipédia et les Attikameks pendant le mois de février. Avant cette présentation, j’avais déjà su un petit peu à propos de chacun des deux sujets, mais j’ai pensé que cela sera intéressant de savoir encore plus.

Wikipédia. Maintenant, je comprends pourquoi les enseignants ont une passion si sévère contre la base de données. Ce séminaire nous a enseigné comment changer la page web dans quelques clics. C’est absurde qu’un site web avec si beaucoup de pouvoir puisse être changé si vite par n’importe qui. Donc, il est juste de dire que les professeurs ont raison de le détester. Quand même, j’ai trouvé la présentation très informative, et je suis content que j’ai appris quelque chose de nouveau.

Les Attikameks. La dernière fois que j’ai entendu, de l’information à propos des Attikameks était au cours de la huitième année, alors c’était la partie de la présentation pour laquelle j’étais le plus excitée. Je trouvais le concept de leur langue très fascinante, et je pensais que c’était formidable qu’ils aient reçu leur propre dictionnaire de Wikipédia. Aussi, les difficultés m’intéressaient, car l’évolution d’une langue par bouche à l’oreille est tellement fascinante. Je sais que cela fait le travail des traducteurs plus compliqué, mais c’est la tradition qui fait la langue unique des autres.

Jeremy Dutcher

I have always loved listening to music, but Indigenous music is a genre that I never encountered prior to joining the Robarts fellowship. Having experienced this Jeremy Dutcher talk I am now intrigued more than ever to find out about Indigenous culture and its relation to music. Dutcher was extremely personable even in an auditorium filled with people. He quickly pointed out the power of music and most importantly the power it can give to a language.

“Language is an assertion of one’s sovereignty”.

This was the most powerful thing I heard Dutcher say as he explained that in his community the number of Wolastoq language speakers is greatly diminishing. Statements like these provide great perspective when looking at other cultures outside of your own. Languages represent the independence and individuality of groups and it is scary to think that, in the case of many indigenous groups, language is fading. I am glad to have participated in this talk because it opened my eyes, and I thoroughly enjoyed myself.

Indigenous Languages Booklet

For this portion of the fellowship I worked closely with my good friend Ana Kraljević. This volunteer effort pushed me more than any of my previous efforts. Ana and I were tasked with editing and recreating the layout of an Indigenous Languages Booklet for the Canadian Language Museum.

I found this experience to be especially rewarding, but it also required a lot of work. Overall, it was a highly enjoyable experience that allowed me to gain knowledge regarding the composition of different Indigenous languages. It was especially interesting to find out that there are different Indigenous language families, which is actually quite similar to how other non-Indigenous languages are grouped. Also, it is interesting that the differences between Indigenous languages are often tremendously subtle. In many cases, it comes down to a slight difference in pronunciation or spelling.

It was truly incredible to work on a project that is so far outside of my comfort zone. I learned that all languages are complex and that Indigenous languages are invaluable. Additionally, I know that the booklet is not a quick read, but I think it is absolutely worth taking time out of your day to sit down and enjoy. We should all try to make an effort to learn more about the groups we share our country with.

Was it worth it?

So, would I recommend the Robarts Fellowship? Of course! My experience was centred around Canada’s Indigenous population, but yours doesn’t have to be. Canadian studies is such a broad subject that there is something for everyone. The Robarts Fellowship helped me to grow and expanded my perspective. Furthermore, it was important in my development as a human being in becoming more aware of other cultures that differ from my own.

Canadian? What is Canadian?

When asked, I always say I’m rather uninterested in Canadian history, and much prefer the history of Europe. Although the opportunity to participate as a Robarts Centre fellow was exciting, I was a little hesitant about the Canadian Studies aspect. When thinking of Canadian Studies, I was reminded of my high school experience of continuously learning about how the railroad connected the west with the rest of Canada. This was interesting enough in isolation, but utterly boring when repeated every year, to the exclusion of learning about Canada in between Jacques Cartier and the rebellions of 1837. (Yes, it’s been almost ten years and I am still slightly bitter about that).

But of course the Robarts Centre provided different opportunities, and different areas in which to reflect on the Canada that we have today, with its common threads and regional differences. (An impromptu family reunion and conversations with my Grandma about our family history also helped reflection there.) Looking back on the project with the Canadian Languages Museum, it was sometimes a wild mess deciding how to approach educating people on Canadian languages. It was a good way to reflect on the multitude of languages brought to Canada through immigration. It also brought consideration to how reactions to historical events has informed the use of language by immigrant Canadians, even those whose ancestors immigrated around the era of confederation.

The question we asked participants was, “What are the strategies you use to preserve your language?” In response, one native French speaker asked us each what languages we spoke. Now aside from being able to hesitantly communicate in basic French, I only speak English, and one single Norwegian phrase that survived my great-grandfather’s purge of the family’s home languages of Norwegian and Swedish. This purge was in response to someone accusing a family member of being “a dirty Finn.” On the other hand, there’s the low German that my grandmother’s family spoke. My grandmother’s family came to Canada from Mennonite settlements in Russia in the 1870’s. All the way through their history of immigrating from one European country to another, they managed to keep speaking their language. But then, of course, history intervened in 1914 and it became wise to not speak German. To this point, according to the wartime census, my family no longer spoke German, but Russian, which luckily for them was an allied nation. Then, of course, came the Russian Revolution, and by the 1930s, my grandma was told to say her family was of Dutch origin. However, even coming from such a patchwork of languages and cultures most have faded over time.

Before participating with the Robarts Centre I didn’t really think of other European languages as relating to the Canadian immigrant history in the same way as I think of more recent immigrant languages from Asia or Africa. My thoughts on that didn’t really connect until I attended the launch of Emily Laxer’s book, “Unveiling the Nation”. Prior to that, I thought of Quebec as being culturally distinct from the rest of Canada, only in a superficial way. However, the way the political debate in Quebec over the veil worn by some Muslim women is framed is completely different than the type of debate on this subject held in English-speaking Canada. The comparison with the debate in France certainly highlights the distinctness of Quebecois political and social culture. Quebec is distinct and has its own laws - that's easy enough to recognize. However, growing up in British Columbia, I learned Quebec’s legal and political distinctions mainly from the childhood memory of seeing the fine print that contests were not available to residents of Quebec. But that doesn’t really explain the nuances of Francophone culture in Canada and how it exists in so many parallels to Anglophone Canadian culture. This is something the average Canadian seems not to think of. Certainly not in western Canada, where the fall of New France was never framed as “The Conquest.” So, when you first hear the term, it sounds overly dramatic. Often, as a Canadian growing up in the West, it's easy to not pay full attention to the politics and culture of Quebec.

So what did I learn from my time as a Robarts Centre Fellow? it is clear that to understand Canada and Canadian culture, one must develop an understanding of its history. (A relatively young history, which can so easily be neglected by Canadians, including me!) Yet for mainstream Canadian society, our history is built on the stories, the language, the traditions and cultures of our ancestors from histories the world over, immigrating and integrating together, into a patchwork society, where not everything is kept but the underlying stories remain. And history continues to grow.

Robarts Centre Fellowship Reflection 2018-2019