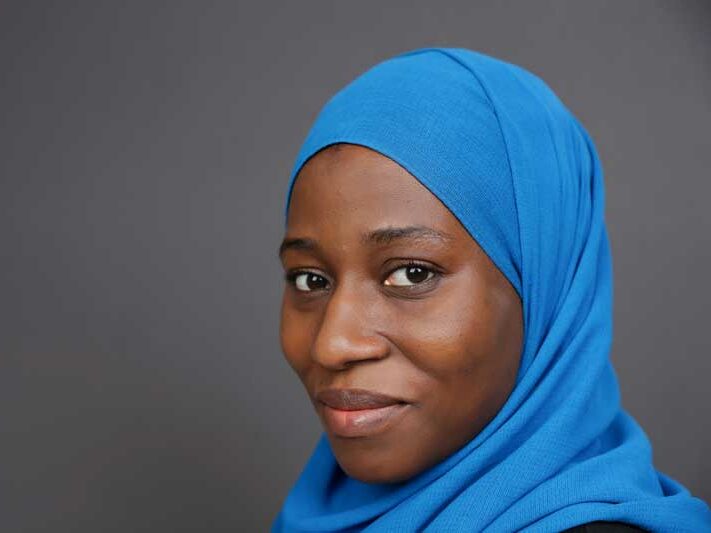

Osgoode Hall Law School Assistant Professor Rabiat Akande was invited to address the United Nations Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of Complementary Standards on July 20 where she asked the committee to consider changes to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

Akande urged the Ad Hoc Committee to strengthen ICERD to specifically prohibit the persecution of racialized religious minorities. Akande argued that international human rights law does not offer these groups adequate protection.

The Ad Hoc Committee was initially formed in 2007 to consider a convention or additional protocols to update the ICERD. The committee has met most years since 2008 and is attended by member states, regional groups, national institutions, specialized agencies, and intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations.

The committee has engaged with numerous experts in the fields of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, and contemporary issues of racism in different contexts. The resumed 11th and 12th sessions of the committee took place from July 18 to 29 in Geneva, Switzerland.

Akande told the committee that a current draft of the additional ICERD protocol, which was drawn up during the 10th session, mistakenly construes all forms of contemporary religious discrimination as racial discrimination and “fails to acknowledge the every day struggle of persons who suffer intersectional discrimination along the axis of race and religion.”

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which helped shape subsequent international human rights law, was fatally flawed because its concept of religious liberty continues to exclude members of disfavored and racialized religious groups, she said.

Akande argued the international law draws a false dichotomy between freedom of conscience (or internal beliefs) and outward forms of religious faith.

“The most obvious casualty has been the covered Muslim woman,” she stated to the committee, “with a string of decisions handed down by the European Court of Human Rights consistently upholding state restrictions and even proscriptions on the hijab – the Muslim headscarf or veil –as being a proportional and reasonable restriction of the manifestation of religion.”

Muslim minorities face the debilitating impact of Islamophobia, said Akande, but are unable to access meaningful legal remedy under the law. At times, she added, the same has been true for other religious minorities, including Jews, Sikhs and even some Christian groups.

Akande said the draft protocol to ICERD “will not offer the legal remedy needed by those whose experience of religious and racial marginalization is compounded by the intersection of those two forms of discrimination.”

She told the committee that the legacy of colonization lives on in the racial and religious subordination of certain peoples – “marginalization that is not only denied recognition and remedy under international law but is in many ways even compounded by the current international legal regime."

“As we confront new forms of oppression such as lethal Islamophobia masquerading as national and international security policy,” she said, “and indeed, the persistent denigration of the religions of Indigenous peoples globally, I hope member states will seize this opportunity to take bold action by offering robust legal protections for communities at the margins.”

Akande joined Osgoode last year, and works in the fields of legal history, law and religion, constitutional and comparative constitutional law, Islamic law, international law and post-colonial African law and society. She is an Academy Scholar at the Harvard University Academy for International and Area Studies, where she was in residence from 2019-21. She graduated from Harvard Law School in 2019. At Harvard, she also served as an editor of the Harvard International Law Journal and taught at the law school and in the Department for African and African American Studies.