By Jenny Pitt-Clark, YFile editor

Twenty-seven years in the making, School of the Arts, Media, Performance & Design Film Professor Ali Kazimi’s documentary about an autonomous Indigenous people's struggle to overturn their legal extinction is set to receive its international premiere.

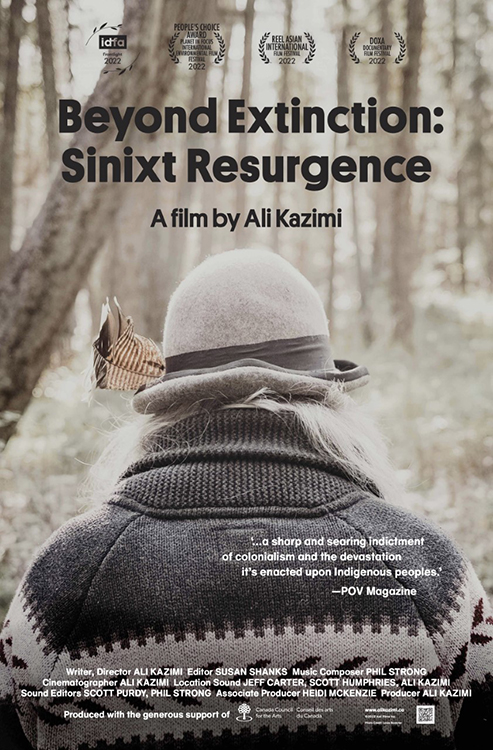

The film, Beyond Extinction: Sinixt Resurgence, is Kazimi’s critically acclaimed, award-winning feature documentary. It recently screened at the DOXA Documentary Film Festival in Vancouver, B.C. in May (co-presented with Rungh magazine). The film garnered The People’s Choice Award at the Toronto’s Planet in Focus International Environmental Film Festival. The film tells the story of the decades-long struggle of the autonomous Sinixt people to overturn their legal extinction by Canada in 1956.

Now the film will receive its international premiere at the highly prestigious International Documentary Film Festival of Amsterdam with four screenings taking place from Nov. 11 to 16. Beyond Extinction: Sinixt Resurgence is the only Canadian feature selected for the 35th edition of this film festival and is among 23 films that will be screened in Frontlight, a program that showcases “a leading cohort of truth-seeking filmmakers who don’t compromise on stylistic integrity.”

Kazimi began documenting the struggles of the Sinixt First Nation peoples in 1995 following an unusual encounter. “A close friend, immigration lawyer Zool Suleman, had recently started his practice and had shared with me a truly bizarre and shocking case. His client, Robert Watt, was being held in detention and was facing deportation to the United States,” said Kazimi. He noted that Suleman indicated that Watt had maintained to Canadian immigration authorities that he was Indigenous and had been appointed as caretaker by the Sinixt Council of Elders to protect an ancient village site and burial ground situated in Vallican, B.C. According to Suleman, the immigration department’s response was that “while that might be true, Watt was not legally recognized as an Indigenous person in Canada since the Sinixt people, then known as the Arrow Lakes, were declared extinct in 1956.” As such, the immigration department maintained that Watt was an American without proper immigration authorization and therefore the deportation order was justified.

The Sinixt traditional territory straddles the Canada-U.S. border, from the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State to Grand Bend, north of Revelstoke, B.C. The arrival of settlers in the mid-19th century led to a rapid dispossession of the Sinixt land. An ensuing smallpox epidemic decimated the Sinixt people and survivors were pushed by colonial violence to seek refuge in Washington State. In 1876, the Sinixt were among the 11 federally recognized First Nations forcibly relocated to the Colville Confederated Tribes Reservation.

In 1989, some residents of Vallican, which is situated in the Slocan Valley in B.C.’s interior, travelled to the Colville reservation to report to Sinixt elders that a new road through their community was going to destroy a recently discovered ancient village site and burial ground. Led by Sinixt matriarch Eva Orr, Sinixt activists headed north to B.C. to set up a blockade. They lost their legal battle, and the road was built, but they occupied the site and prevented B.C. authorities from constructing a tourist information kiosk on the ancient village site and burial ground, the very site that Watt was protecting for many years before he was detained by immigration.

In 1995, after hearing the story of Watt and the Sinixt struggle, Kazimi reached out to Marilyn James, the official spokesperson of the Sinixt. After several weeks of phone conversations, James invited Kazimi to attend the annual Thanksgiving gathering at the site. The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) was interested in the idea about a film on the Watt case. Kazimi used the limited funds he received from the NFB to produce seven hours of initial recordings that are now the core of the film.

“From the moment I arrived at the site I was met by Marilyn, Eva and the other elders with open hearts, it was one of the most transformative moments in my life. I was given access to everything, including strategy meetings and discussion,” said Kazimi. “This is the privilege of being a documentary filmmaker and I never take it for granted because with it comes deep responsibility.”

Kazimi learned that Orr was one of the last fluent Snsəlxcín speakers, and when asked, she agreed to narrate the survival story of the Sinixt in their language. This unique recording of the Frog Mountain story in Snsəlxcín, is now a vital part of a language revitalization program.

Progress on the film stalled, and in 1995, unable to get a green light for the film, Kazimi was forced to put the project to one side. In what would later be an insightful decision, Kazimi held on to the material he had filmed. Over the ensuing years, he also continued to follow the legal and activist developments of the Sinixt people.

In 2019, after he received the Governor General’s Award for Visual and Media Arts, Kazimi decided to use the award prize funds to restart the Sinixt project.

“Archival materials, especially moving images, form the core of my practice as a filmmaker. Now I was going to dig into my own archive, which simultaneously was also part of the Sinixt archive,” he said. In addition to his own archival materials, James gave Kazimi full access to her archive, which included documentation of events, actions, as well as home movies. Critical clips from films such as Bones of Our Ancestors by Slocan Valley filmmakers Max and Virginia Frobe were generously offered, as were clips by films made by the Slocan Narrows Research Project led by archeologist, Nathan Goodale of Hamilton College, N.Y.

After two years of filming, gathering archival materials and creating an assembly for the film, Kazimi, backed by a strong letter of support from James, secured a grant from Canada Council for the Arts to complete the project. At the conclusion of production, Kazimi returned to B.C. to screen the film to the Sinixt First Nation communities. Screenings were held in Nakusp, Nelson, Trail, Castlegar and Vallican.

Osgoode Hall Law School Professor Amar Bhatia, who has shown Kazimi's other documentaries in his courses, reached out to Kazimi to screen the film for his Indigenous Law course. “This is a powerful film that tells lesser-known aspects of the story of the Sinixt people, predating the border between Canada and the U.S., but touching on so many contemporary themes and flashpoints, including the impact of colonial Canadian laws, the Indian Act, residential schools, and logging,” said Bhatia.

Beyond Extinction: Sinixt Resurgence also plays at Toronto Reel Asian International Film Festival on Saturday, Nov. 12, at 2:30pm in Cinema 4 at the TIFF Bell Lightbox. The festival is also streaming the film from Nov. 14 to 20.