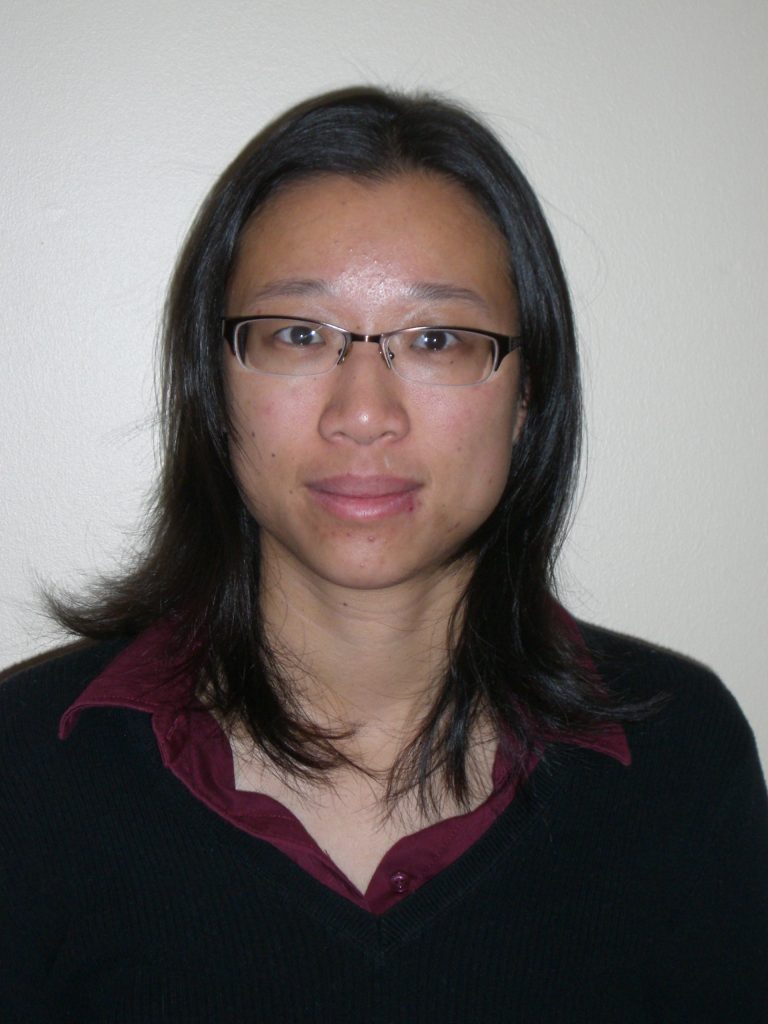

Led by York University Faculty of Health Associate Professor Jennifer Kuk, a new long-term study of population-level data shows that when it comes to health, not only could everyone make improvements, but the relationship between risk factors and mortality changes over time, sometimes in surprising ways.

“You can take this as a good news story or a bad news story, depending on how you want to look at these numbers,” says Kuk, who was lead author of the study published recently in the science journal PLOS One. “What we discovered is that the relationship with risk factors and mortality changes over time, which could be explained by factors such as evolution in treatments and changes in social stigma. Overall, most of us have something wrong with us, and we’re more likely to have a lifestyle health-risk factor now than in the 1980s and that’s actually associated with even greater mortality risk now than before.”

The research took United States survey data from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2014, and looked at the five-year mortality odds for people 20 years or older. The research team looked at 19 different risk factors and then adjusted the data for age, sex, obesity category and ethnicity. What they found overall was that less than three per cent of people had none of the risk factors. While previous research has documented the risk factors very well, Kuk says what was less understood was the relationship between various risks and the likelihood for mortality over time. Kuk and the research team found that the relationship could sometimes be paradoxical.

For example, says Kuk, rates of smoking, long linked to conditions that can lead to death such as cancer, heart disease, stroke and diabetes, have overall decreased thanks to strong public health campaigns. However, the overall risk of being a smoker increased over time, which Kuk says could perhaps be explained by increased stigma as the addiction became less common and awareness of risks grew, which may also be reflected in research funding.

“If you look at cancer research, there's a lot of funding overall. But specifically lung cancer seems to be associated with moral fault and, as a consequence, receives lower funding,” says Kuk. “When you look at the mortality risk associated with having lung cancer relative to all the other common cancers, it's extremely high. So I think that this lack of push is detrimental.”

Kuk’s main area of research is obesity, and here she found that while its prevalence has gone up, the risks have gone down.

“Even though there's more and more people with obesity, it's actually not resulting in more deaths over time. And so I think that that's another clear thing we need to recognize, that we're very good at treating the outcomes associated with obesity. And regardless of what our body weight is, most of us have something that we can probably work on.”

Some of the other health trends that Kuk found in the data include:

- diabetes and hypertension rates have gone up over time, but risks have gone down;

- more people aren’t exercising, and this is now related to worse outcomes than it once was;

- being on mental health medications was not a significant risk factor in the 1980s, but in the later dataset was associated with increased mortality; and

- not finishing high school is now associated with health risks, but was not in the 1980s.

While Kuk says the research points to nearly all of us having room for improvement when it comes to various factors like diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol and drug intake, she also says that there are factors that are out of many people’s individual control.

“When we look at things like food insecurity, low education – as a society, we're making it so that health might not be an easy choice for a lot of people. We need to be sensitive to that when we take a look at these risk factors.”

Watch a video of Kuk explain the research.