Spend an afternoon taking one of Natasha Henry-Dixon’s self-guided walking tours of downtown Toronto and you get a glimpse into what it was like to be Black in Upper Canada and the old Town of York centuries ago.

Brought in Bondage: Black People Enslaved in the Town of York exposes participants to the unique experiences of people of African descent who arrived in early Toronto in the late 1700s through forced migration enslaved by white Loyalist settlers.

Fast forward to the mid-1850s, and a second walking tour, Tracing Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s Footsteps in Mid-19th Century Black Toronto, offers a glimpse of the Toronto encountered by Shadd Cary, a Black newspaper publisher and abolitionist who lived among a community of Black people working hard and advocating for racial equality.

“These tours are a meaningful way to locate Black people, enslaved and free, firmly within the landscape of Canada’s largest urban centre,” says Henry-Dixon, a Black historian and assistant professor in York’s Department of History. “The walking tours are a way of making this history more readily available.”

Born and raised in Toronto, Henry-Dixon wondered how long Black people had been in Toronto. How did they get here? What did they do? She has spent many of her adult years trying to answer those question for herself and others, pouring over archives, diaries, financial ledgers and letters to close a gap in the knowledge about slavery in Upper Canada and Black experiences in Ontario.

Henry-Dixon’s research reveals that although many don’t associate Canada with slavery, the enslavement of Black people existed here and continued for 200 years until it was abolished across the British Empire by the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

Through her research project, One Too Many: Black Enslavement in Upper Canada, 1760-1834, she has uncovered the existence of 624 Black men, women and children who were enslaved in Colonial Ontario. It’s a way to establish Black presence in early Toronto, and to humanize these early residents and help shed light on their experiences and contributions.

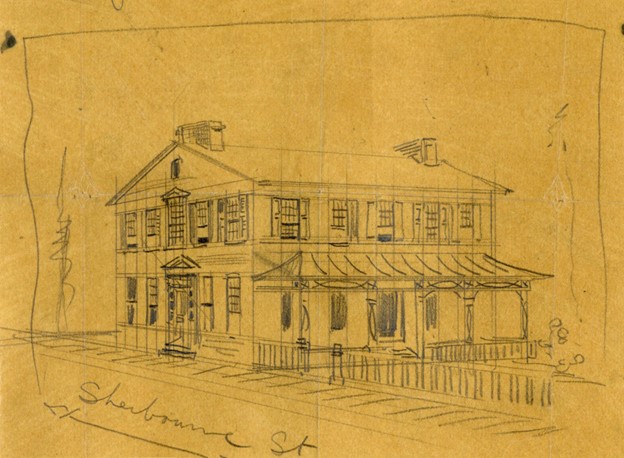

For example, to stop by 363-365 Adelaide St. E. near Sherbourne Street is to visit the former site of Jarvis House, the sprawling home to William Jarvis, provincial secretary of Upper Canada in the late 1790s, and his wife Hannah and their children. The two-acre property also featured slave quarters built to house the six Black people they held in bondage.

On the site of 37 King St. E., now home to the King Edward Hotel, there was a log hut that served as a local jail, where Black people enslaved in the town were imprisoned for defying the orders of their enslavers, or for running away.

Years later, but not far away at what is now the area of Church and King streets, is the St. James Cathedral, where in the mid-1800s Rev. Henry Grasett led an integrated congregation, marked Emancipation Day services each year, and oversaw the marriages and baptisms of the many Black people who attended his church.

In 1854, Mary Ann Shadd Carry moved the Provincial Freeman – the first newspaper published by and for Black people – from Windsor to what is now 143 King St. E. She was the first Black woman and woman of any race in North America to publish a newspaper. The paper advocated for the abolition of slavery in the United States and promoted emigration to Canada for freedom seekers and free Black people.

The walking tours, which are enabled by GPS, invite users to contemplate how Black people in early Toronto lived and can be accessed from Henry-Dixon’s website. The site includes, among other resources, a biography of John Baker. The last known surviving slave in Upper Canada, Baker was born into slavery in Cornwall. He lived in the Town of York with his enslaver, Robert Gray, Upper Canada’s first solicitor general, and freed upon Gray’s death and went on to serve in the War of 1812.

Henry-Dixon says she named her website One Too Many to advance the idea that Black slavery in Canada was significant, even if numbers do not compare to that of the U.S. or the Caribbean.

“It doesn’t matter the number,” she says. “That this institution took hold and existed for over 200 years in the beginnings of Canada says something about our history, and it also places these individuals here in this space. So what can we learn more about them? How can we honor their presence?”

Learn more about the work of Henry-Dixon.