|

|

| | |

| | VOLUME 30, NUMBER 12 | WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 1, 1999 | ISSN 1199-5246 | | |

| | ||||

|

|

By Chris Stewart and Roman Koniuk Peer into the sky towards the constellation Cygnus, the Swan, near the horizon this month. One of the most interesting objects up there is one that, no matter how hard you try, you will never see. Up amongst the stars, hidden from us by its own gravity, is a black hole, and it's the closest one to the Earth at just one thousand light years away. Black holes are perhaps the strangest objects in the universe. To understand them, we should first talk a little about Einstein. Early this century, Albert Einstein developed his theory of gravity known as General Relativity. Before Einstein, space and time were always part of the background, the playing field on which the games of physics were held. Objects moved through space, changing their position against the regular heartbeats of time. Relativity says, however, that space and time - together known as space-time - aren't just labels for where an object is found. Space-time itself is a real dynamic entity. In the vicinity of a massive object like a star, space-time is curved. Curved space-time isn't easy to imagine, even for physicists. Try this: imagine you've got a nice big, soft king-sized bed. If you roll a bowling ball across the bed, the ball sinks down a bit, deforming the bed's surface into a curved dip as it goes. Place a bowling ball in the middle of the bed, and roll a marble across the mattress - the marble will, of course, follow the dip of the mattress down towards the bowling ball, along a curved path. The mattress is a bit like space-time, the bowling ball like a massive object, such as a star. The mass of a star warps the space-time around it, and any object coming near the star will follow a curved path through the curved space-time. The Earth does this as it orbits the Sun; it traces out an ellipse in the space curved by the enormous mass of our nearest star. Einstein became a bit of a celebrity, however, for suggesting that even light itself gets bent as it passes a heavy object. Careful observations have verified this effect. They have shown that a distant star seems to shift position in the sky a little when the Sun passes in front of it - the light coming from the star is bent by the Sun's gravity, and the amount of the bending is exactly the amount predicted by Einstein's General Relativity. Headlines shouted "Einstein Proven Correct!", and his face began to appear in newspapers, magazines and on coffee mugs and t-shirts. What's all this to do with black holes? Well, what if you had an object so massive that passing rays of light would bend so much they would spiral down towards the object, never to escape? Any light trying to leave the surface of this object would be pulled back. And if light can't get away, then nothing else can either, since nothing in the universe can travel faster than light. Such things are perfectly acceptable results of General Relativity. Theorists dubbed them "black holes" since light can't escape to show us what they look like. You really wouldn't want to stumble across one of these things. The incredible gravitational pull of the black hole wouldn't just drag you towards it, it would do very odd things to your body in the process. For one thing, the gravitational pull on your feet would be stronger than on your head. This is true if you're standing on the surface of the Earth too, the pull towards the ground is ever so slightly greater at your feet than up at your head. We don't notice this because the difference is incredibly small. But near a black hole, your feet would drop away and your body would stretch out like so much spaghetti. So how do we know there really is a black hole in Cygnus? That's the thing about black holes: they're black, we can't see them directly. We can, however, tell they're around by looking for the effects of their gravity on nearby stars. Astronomers observed that a large star in the constellation Cygnus appeared to be orbiting around some other, very heavy object. When they looked to find the other object, though, there was nothing there. Just as odd, the star was emitting huge blasts of x-ray energy, as if its surface was being ripped apart and dragged away. Astrophysicists calculated that these effects must be due to a black hole very near to that star, and dubbed the system"Cygnus X-1". The "X" is for the X-rays bursting from it, and the "1" means it was the first black hole they found. So as you peer into the night sky this month, just think what a wonderful poetic twist it is, that deep within the constellation of Cygnus, in the very heart of that graceful white swan, lies one of the darkest and strangest denizens of the sky. Chris Stewart is a doctoral student in physics and astronomy and Roman Koniuk is Chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy. Stewart and Koniuk are themselves simulating dynamic fields on a space-time lattice. This work is featured on the Apple Canada Web site: www.apple.ca/ education/dartagnan/.

| |||

|

|

By Susan Scott York history Professor Marlene Shore one of the speakers at the second Millennial Wisdom Symposium Three speakers shared their views about what history has taught modern society and whether or not people can learn from it, during the second Millennial Wisdom Symposium, the brainchild of award-winning author and York Professor Susan Swan and organized by York's Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies. Acclaimed author, Ronald Wright uses historical references in his fiction to give people a glimpse into the future. In his novel, A Scientific Romance, the main character is a specialist in Victorian machinery who finds himself time-travelling in a machine reminiscent of that in H.G. Wells' novel, The Time Machine, which tells the story of a man who travels into the future to find an upper class society and a sub-human class. He discovers the latter is really preparing their upper class colleagues to be a food source. In A Scientific Romance, the time-traveller visits 2500, and finds Britain overgrown with jungles and sparsely-populated with a band of illiterate Scots who enact a version of playwright William Shakespeare's Macbeth, as an annual fertility festival. Wright said authors like Wells and William Morris "voiced their concerns" about the future in their novels. Other more contemporary examples include George Orwell's 1984 and Adolph Huxley's Brave New World, which also discuss what Wright described as the optimism about technological advances turning into pessimism about its consequences for future populations. He said those authors asked questions about the effect of the fast pace of technological change on resources like water and air. Today, he said "we see the results" with, for example, pollution. As the world this year marked the birth of the six billionth person, Wright remarked that there are now 20 times more people than there were just over 500 years ago and that "more than half that increase has happened in the last 50 years." Such population growth affects issues like climactic stability but "these are things that decay slowly, we can't see them," he said. Authors such as Wells and Morris may have foreshadowed these events in their novels, however Wright said there's little being done to stop these trends. Marlene Shore, a history professor at York, discussed Canada's place in history and its future in the 21st century. She said Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier predicted the 20th century would belong to Canada, but Shore asked "will Canada belong to the 21st century?" Despite its status as a leader in information technology, she said some Canadian businesses have shunned their nationality. For example, telecommunications giant, Northern Telecom uses the shortened Nortel. Another example is bookstore chain Chapters whose internet address is chapters.ca. "These are Canadian companies that want to think globally but don't want to promote themselves as Canadian," said Shore. "The internet and global competition may erase Canadianism." She said there's a trend toward Canadians viewing themselves more as North Americans rather than as Canadians within North America. Historians have traditionally been asked to predict future trends, often in the midst of political scandals, national debates and world crises, said Shore. This demonstrates that historians are regarded by some as "spokespeople for the nation." Many historians in the western world adopted that role in the late 19th century when, for example, those in French and English Canada put themselves forward as moral leaders of society whose understanding of the past, reconstructed into readable narratives, would provide their communities with the solid foundation on which to build the future. "This view was shattered by the Second World War, and more particularly during the 1960s," said Shore. "What followed was a proliferation of historical writing about peoples and even ideas once relegated to the margins of the so-called national past - a role taken up by political scientists and economists - and whether they should re-engage themselves in the public debate, especially in view of today's enormous popularity of history and historical memory in fictionalized form - in literature, on film, in much popular culture." Tim Kaiser, adjunct professor in anthropology at York, has spent the last 20 years in the Balkan region, primarily Bosnia and Croatia. "How can things like this happen if we had learned from the past," he said. "Nowhere has it been made more horrifyingly clear that the past is a prize, a resource to covet and contest, than in the west Balkans today." Kaiser said Balkan leaders mistakenly tried to create an ethnically homogeneous society, but "homogeneity never existed, or if it did, only briefly. Therefore, this tendency is to produce one effect, homogeneity, by using history as a political target." As an example, he pointed to the destruction of monasteries and bridges during the war in the region. "Why was this done? Not for military value but for cultural reasons. They're pieces of the past that intrude on the present and if you destroy symbols of the past, you work to destroy your enemy," Kaiser said.

| |||

|

|

At its meeting on Friday, Oct. 1, 1999, the Board of Governors received for information a report from the Executive Committee on the following items approved under provisions of Summer Authority: 1. Approval of the appointment of Dr. Terry Piper as Dean of the Faculty of Education, for a five-year term effective Oct. 1, 1999. 2. Approval of a collective bargaining mandate for negotiations with the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) Local 3903 (part-time contract faculty and teaching assistants). 3. Ratification of Memorandum of Agreement with CUPE Local 1356 (covering eight to ten part-time and casual employees in an appendix to the existing CUPE 1356 collective agreement). 4. Ratification of a Collective Agreement with the York University Staff Association (YUSA) for the period Aug. 1, 1999, through July 31, 2000. 5. Approval of a new Purchasing Policy (enabling the University to use its leverage to enhance purchasing power). 6. Approval of a compensation mandate for employees in the Confidential, Professional and Managerial (CPM) group. 7. On the advice of the Audit Committee, approval of the University's financial statements for the fiscal year ended April 30, 1999. 8. Confirmation of the appointment of Eileen Mercier as a member of the Pension Plan Board of Trustees with a term to expire on June 30, 2000, and re-appointment of John Bankes and Robert Martin as members of the Pension Plan Board of Trustees with terms to expire, respectively, on June 30, 2001, and June 30, 2002. 9. Approval of a change in the terms of reference of the Pension Plan Board of Trustees to authorize the addition of a representative to be appointed to the board by CUPE 1356-1. 10. Approval of the appointment of Marshall Cohen, Fred Gorbet and Nalini Stewart as board representatives to the Senate. 11. Approval of board committee assignments as reported to the June 21, 1999, meeting, with the following additions: Charmaine Courtis to the Student Relations Committee and Maurice Elliott to the University Advancement Committee and the Student Relations Committee. 12. Approval in principle of the president's recommendation that the position of vice-president (research) be established.

| |||

|

|

Applications and nominations are invited for the position of Director of the Institute for Social Research (ISR), for a term of three years, to begin if possible January 1, 2000. The Institute for Social Research promotes, undertakes and critically evaluates applied social research. In addition to research services for the York community, ISR conducts projects for researchers at other universities, government agencies, public organizations and the public sector. The capabilities of the Institute include questionnaire and sample design, sample selection, qualitative research design, focus group research, data collection, preparation of machine readable data files, statistical analysis and report writing. ISR is the largest university-based survey research unit in Canada. Candidates must be members of the full-time faculty at York University, and have a distinguished record of scholarship, including experience and expertise in applied social research. Demonstrated skills and experience in administration, budget management and negotiation of research grants and contracts would be required. The successful candidate will foster a collegial work environment, and ensure that ISR is a visible and respected presence at York both through her/his own standing and active promotion of the Institute. The director will report to the associate vice-president (research). The successful applicant will receive an administrative stipend and an appropriate course load reduction. Applications and nominations (including curriculum vitae and names of three referees who may be contacted) should be sent to the Secretary of the Search Committee, Carol Irving, Executive Officer for Research Centres, Office of the Associate Vice-President (Research), S945 Ross Building. Applications and nominations received by December 6 will receive the full consideration of the search committee.

| |||

|

|

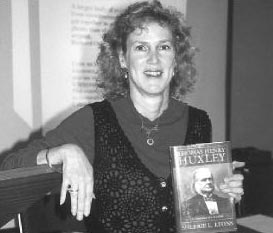

By Cathy Carlyle Sherrie Lyons talks about sea serpent investigations. Probably the most famous sea serpent of our day is the Loch Ness Monster. Scientists have spent long hours trying to prove - or disprove - its existence. In Victorian times sightings of sea serpents abounded and, just like today, scientists took up the challenge of finding out if such creatures were real. Sherrie Lyons, formerly of Daemon College and now on a National Science Foundation grant, believes that the boundary between fact and fanstasy is not as sharply-defined as many scientists would have people believe. "Just as in the 19th century, the sea serpent continues to capture the imaginations of not just a gullible public but leading scientists as well," she said at a York Brown Bag Seminar in November. As science gradually came to be viewed as a serious subject in the 1800s, those studying it wanted to see facts connected to theory and a "neutral objective means of inquiry", said Lyons. For instance, geologists, vying for recognition as scientists, wanted to distance their investigations of natural history from that of myth and legend. "However...it is precisely the developments in science that were responsible for the revival of interest in the serpent," said Lyons, adding that exploratory voyages increased dramatically in the 19th century and explorers not only charted seas but brought back "a wealth of exotic organisms never seen before...to be dissected and classified". "The 19th century witnessed the discovery of all sorts of fantastic creatures in the form of fossil remains. Real evidence of 'monsters'...who swam in the seas of ancient times brought about a renewed curiosity about the existence of present-day monsters. It was not mere coincidence that as paleontologists began dredging up plesiosaurs and other relics from the past, a dramatic increase in sightings of sea serpents also occurred," she said. These new specimens intensified a debate between Charles Lyell, who believed that the history of the earth showed a pattern of endlessly repeating cycles, and scientists such as Georges Cuvier, who held that the fossil record showed the successive appearance of increasingly complex organisms. Lyell said that the fossil record only looked progressive because of its incompleteness. Victorian naturalist Richard Owen disputed all reports of so-called relics from the past, believing the animals to be creatures such as the sea elephant or works of people's imaginations. "He used his attack on sea serpent 'evidence' to discredit Charles Lyell and his antiprogressionist view of earth history," said Lyons. "Owen maintained that all the eyewitness accounts were worthless if one did not have corroborating evidence in the form of actual specimens. He pointed out that not one skeleton, not even one bone of a nondescript or indeterminable monster had ever turned up". Lyons said that there were heated debates in respected journals such as Nature and Zoologist, as to what the sea creatures might be. Naturalists acknowledged that there had been hoaxes but added that not all of the fossil remains and sightings should be dismissed outright. However, serious geologists and paleontologists began to consider the investigation of sea monsters as pseudo science and not worthy of professional scientists' time. She said the rise of such serpents as a topic worthy of discussion in the 19th century paradoxically was what evenutally pushed it to the margins of science. The discoveries of the fossils of new and unknown creatures that led to people's testimonies about seeing sea monsters, also gave rise to the newly-formed disciplines of geology and its sub-specialty, paleontology in which scientists demanded proof of the existence of the monsters.

| | ||

| | Current Issue | Previous Month | Past Issues | Rate Card | Contact Information | Search |

|